All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Press is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA , a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges, and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, visit intervarsity.org .

Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and DyingTyphoon Coming On, by J. M. W. Turner (17751851): Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Wikimedia Commons.

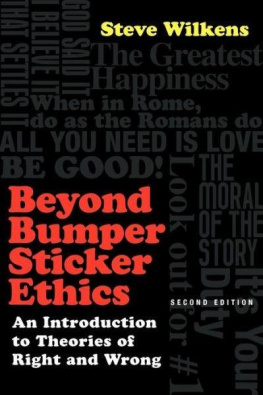

Names: Wilkens, Steve, 1955- editor.

Title: Christian ethics : four views / edited by Steve Wilkens ; with

contributions by Brad J. Kallenberg, Claire Brown Peterson, John Hare, and

Peter Heltzel.Description: Downers Grove : InterVarsity Press, 2017. | Series: Spectrum

Multiview Book Series (SPEC) | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017005115 (print) | LCCN 2017008469 (ebook) | ISBN

9780830840236 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780830891573 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Christian ethics.

Classification: LCC BJ1251 .C496 2017 (print) | LCC BJ1251 (ebook) | DDC

241--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017005115

Introduction to Four Theories of Christian Ethics

STEVE WILKENS

As far as we can tell, humans alone are endowed with a conceptual category inhabited by words like duty, evil, justice, rights, law, mercy, and virtue. In fact, we seem incapable of thinking about our world apart from the vocabulary of fairness, goodness, crime, love, guilt, and blameterms loaded with moral meaning. Moreover, ethical terms and the concepts behind them perform a unique task. They do not simply describe a state of affairs; they go beyond the declarative world of is and speak in the language of should and ought. A particular action may be accurately described as theft or a murder, but these labels are more than just the observation of fact. Theft and murder are prescriptive words; they refer to that which ought not be and take us into the universe of standards, responsibility, and obligation.

Another notable observation about our moral impulse is that we often prefer to act contrary to its direction. We believe that we ought to think and behave in a certain manner and simultaneously desire to do something quite different. This battle between moral beliefs and actual inclinations is the dark side of the ethical mystery, and it is never too far from the surface throughout our discussion. However, embedded in the tension between our desire and our sense of duty is a related puzzle. What is the source of this moral sense? Since ethical beliefs impose demands on us that often run contrary to our desire and behaviors, these obligations seem to originate in some external authority. But what is this authority?

While these theories reduce the moral impulse to purely psychological, social, or biological origins, this should not obscure the reality that most thinkers throughout history have concluded that our sense of moral duty cannot be explained apart from an external and transcendent reality. In the ancient world the metaphysical foundation was known by names like the Good, Logos, the Decrees of Heaven, Pure Being, or the One. Christian intellectuals often borrowed heavily from these ancient sources in framing their own ethical ideas. However, Christianitys concept of a good and personal God who becomes flesh in Jesus Christ is very different from an impersonal Form of the Good or the Greek Logos. Likewise, while classical Greek thought generally doesnt have a concept of creation ex nihilo (from nothing), this Christian doctrine tends to cement the connection between God and goodness. If God creates all things, this also seems to include the moral status of all things. Thus, belief in God as a personal and moral being who is responsible for and involved in creation seems to eliminate the possibility of separating God and goodness.

Christianity and Ethics

Despite broad agreement within Christianity that moral goodness is a divine attribute and is revealed in Gods work within history, particularly in the person and work of Jesus Christ, Christians are often divided on moral theory. Several reasons exist for these divisions. First, we are shaped by different theological traditions that place different accents on, or offer contrasting interpretations of, the divine attributes. Thus, the texture and direction of our moral considerations will be influenced by whether we begin from divine justice, reason, goodness, or sovereignty, and they will be further shaped by specific notions of what is entailed by these attributes.

Second, Christians differ about how God communicates moral knowledge. Is it mediated solely via Scripture, through the ongoing story of Gods formation of a people, through experience and reason, or by some combination of these elements? These factors will also inform the extent that Christian ethicists look to sources beyond Scripture and theology for guidance. To what degree is it permissible to allow philosophy, science, social theory, and other disciplines to inform our moral conclusions?

Variations in Christian ethical approaches also arise from differing anthropological conclusions. How is human reason related to our volitional capacities? To what extent does sin dull our God-given capacities, and does grace enable us to respond to Gods moral and spiritual demands prior to or after justification? Is sin and evil to be viewed primarily as an individual issue, or is it manifest most distinctly in the disruption and perversion of social structures and relations? Should we expect the moral Christian individual or community to exhibit continuity with general moral expectations, or is Christian ethics characterized by contrast and discontinuity with conventional morality?

Finally, while ethical discussion often focuses on the individuals decisions about moral questions, Christian ethics encompasses social life as well. Thus, we will encounter divergences about the place and role of the body of Christ in ethical formation and how the believer is properly related to communities and institutions outside of faiths sphere. Does faith call Christian communities to stand apart as a contrast model to fallen systems? Do ethical demands drive us into conversation and grassroots engagement with the social problems of ones culture? Is it legitimate to form coalitions with those who do not share our Christian faith to combat social ills, or is the Christian worldview so distinct that partnerships with nonbelievers ultimately dilute or denature Christian motivations and modes of social action and witness? All these factors influence how Christians move from doctrine to formulate a Christian approach to ethical matters.

Ethical Systems

When ideas are designated as systems, paradigms, or some other synonym, we inevitably create distortions. Thus, we admit to a certain degree of necessary misrepresentation in the categorizations within this book. First, this process will often join under one heading thinkers who will differ sharply at important junctures. Second, just as reality is often too messy to keep everything in its designated compartments, ideas from one system often overlap in significant ways with others. Thus, for example, various commentators designate Aquinas as an exemplar of divine command theory, virtue ethics, or natural law theory, and do so with some justification. As a result, we admit that those familiar with the field will be justified in questioning whether specific groups and individuals have been properly identified.