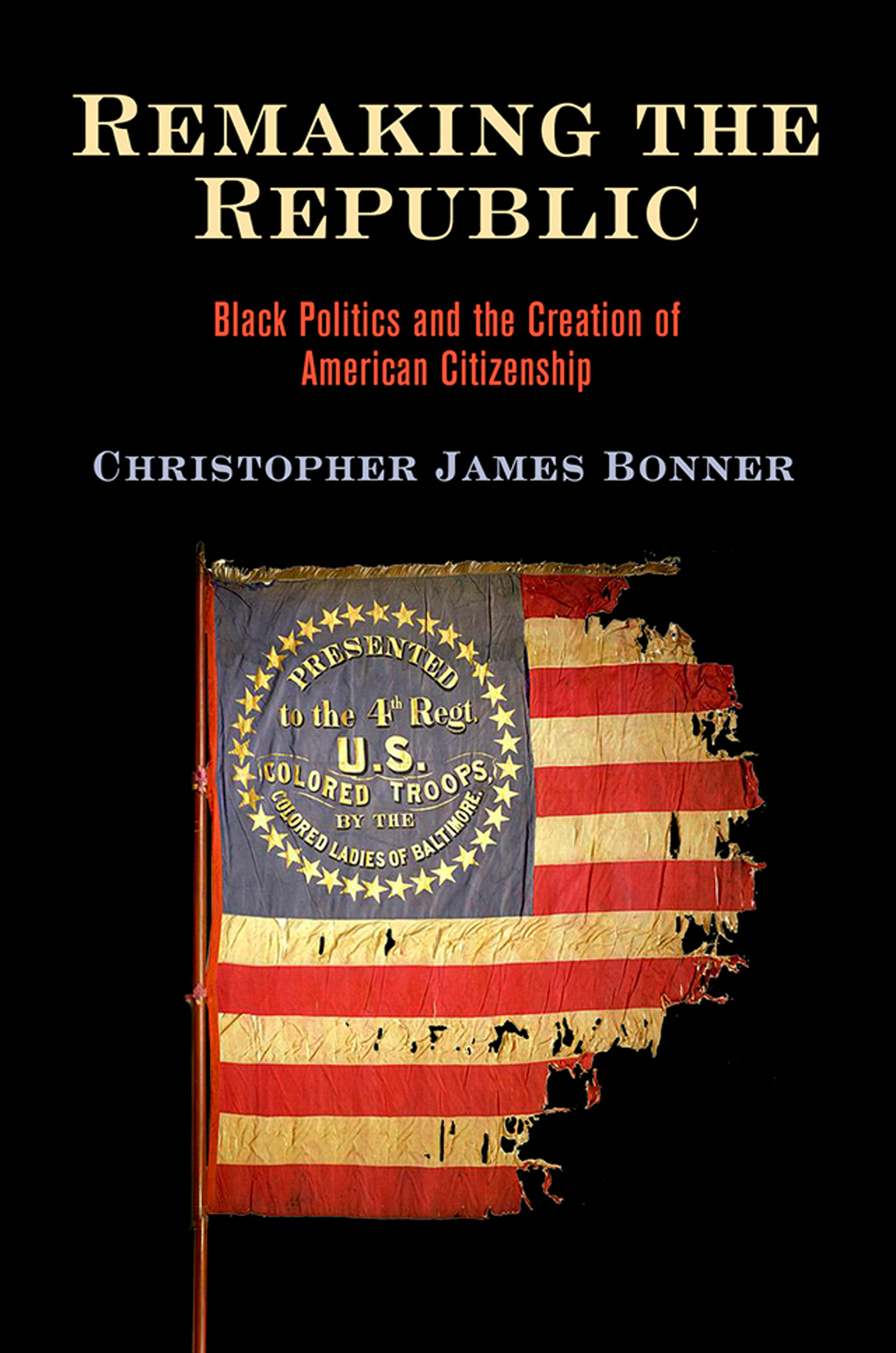

Remaking the Republic

AMERICA IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Series editors:

Brian DeLay, Steven Hahn, Amy Dru Stanley

America in the Nineteenth Century proposes a rigorous rethinking of this most formative period in U.S. history. Books in the series will be wide-ranging and eclectic, with an interest in politics at all levels, culture and capitalism, race and slavery, law, gender, and the environment, and regional and transnational history. The series aims to expand the scope of nineteenth-century historiography by bringing classic questions into dialogue with innovative perspectives, approaches, and methodologies.

REMAKING

THE

THE

REPUBLIC

Black Politics and the Creation of American Citizenship

Christopher James Bonner

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2020 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ISBN 978-0-8122-5206-4

For my parents, Ramona Bonner and James Bonner

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Making Black Citizenship Politics

What is striking is the role legal principles have played throughout Americas history in determining the condition of Negroes. They were enslaved by law, emancipated by law, disenfranchised, and segregated by law; and, finally, they have begun to win equality by law.

Thurgood Marshall, Reflections on the Bicentennial

of the United States Constitution, 1987

John Brown Russwurm sat at his desk on a winter day in 1829 to write an essay explaining why he could no longer live in the United States. Russwurm had been born in Jamaica in 1799, the child of a white American man and a woman of African descent. Little is known of his mother. She may have been free or enslaved, may have been African or of mixed parentage, and may have died in childbirth or lived to see her son leave Jamaica when he was eight years old. Russwurms father gave the child parts of his name and his privilege, sending young John to school in Montreal in the early 1800s, then inviting his black son to live with his white family in Portland, Maine.

Russwurm was an immigrant, a background that likely shaped his feelings about the possibilities of the United States. When he graduated from Bowdoin College in 1826, he delivered a commencement address that praised the accomplishments of the Haitian Revolution and the republic it created. Haiti, Russwurm said, revealed the principle of liberty that dwelt in men of all colors. Russwurm considered studying medicine and emigrating to Haiti to help the country become an empire that will take rank with the nations of the earth. But by the spring of 1827, he had put down roots in

From the papers office at No. 5 Varick Street, blocks away from the Hudson River in lower Manhattan, Russwurm and Cornish had considered the many schemes in action concerning our people.

In February 1829, the new editor-in-chief announced his decision to leave the United States in terms that surprised and alarmed other activists. Our views are materially altered, Russwurm wrote, declaring that he was now a decided supporter of the American Colonization Society.

While Russwurm did not believe black citizenship was possible in the United States, other African Americans understood that the meaning of citizenship was unsettled and that this instability might help them change their legal lives. Free black activists in the northern states publicly challenged racial exclusion by calling themselves citizens, invoking the status to claim specific rights. Because the terms of citizenship were uncertain, the status was a flexible and potent tool for African American politics. Black protest spurred conversations about citizenship among state and federal lawmakers, most notably Chief Justice Roger Taneys 1857 effort to deny that any black person could be a citizen in the United States. African American activists used citizenship in ways that shaped the long process of defining the nations legal structures.

Just weeks after Russwurm embraced colonization, Samuel Cornish returned to New York City and launched the Rights of All, the nations second black newspaper. Cornish and other free black people saw possibility and power in the concept of citizenship. When Russwurm denied that black people could be citizens, he sparked immediate, forceful opposition because other black activists wanted to use citizenship to seek rights and protections. That form of protest grew out of their opposition to Russwurm and became a critical thread in antebellum black politics.

Free black Americans overarching political goal was to change the legal circumstances of their lives. The malleable nature of citizenship made the status an important tool in that pursuit. In the era of the American Revolutionary War, lawmakers in several northern states enacted measures to gradually abolish slavery. But legislators and judges also constrained black freedom, denying black men the vote, excluding them from militias, and considering measures that would force African Americans out of their states. Black people relied on the concept of citizenship to challenge those restrictions and seek specific rights and protections. Remaking the Republic is the story of that political work as it developed from the 1820s through the 1860s across the free states. This book examines how and why black people called themselves citizens and the meanings of that particular form of their politics. Exploring their political work from this perspective illuminates the legal possibilities of citizen status and the ways African Americans took part in re-creating the legal order of the United States in the nineteenth century. African Americans were active participants in the process of constructing citizenship, determining to whom the status was available and what its content would be.

Black people were able to use citizenship in their politics because there was no agreed-upon definition of citizen status in the law of the early United States. That uncertainty provided a space for black politics to operate, enabling African Americans to claim legal protections through citizen status.

Although citizenship could be a path to rights, no decisive legal statement declared that the status must be the foundation for an individuals legal identity. Citizenship remained vague for so long in part because many lawmakers and others did not agree that the status was important for defining identity or securing legal protections. The vagueness stemmed in part from the fact that the framers of the Constitution refused to resolve essential questions about the relationship between states and the federal government. It was unclear how the legal authority of the states related to one another and to that of the national government, and so it was also uncertain to whom an individual should turn to resolve disputes about his or her rights or which level of government would be the operative authority in shaping peoples legal lives. State and federal governments legislated and adjudicated questions of rights and obligations, and it was not clear how citizenship might be crafted or administered on either the state or national level or through some combination of the two. Many people in the early United States looked to local courts for justice and had little sense of close ties to the federal government. Generally, authority was decentralized and individuals legal lives were individual, particular to their contexts, personal connections, wealth, gender, and race.work, black people built a new republic, one that rested on a legal order in which citizen status connected individuals to the federal government through a web of rights and obligations.

Next page

THE

THE