Published in 2019 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2019 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2019 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Executive Director, Core Editorial

Andrea R. Field: Managing Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Carolyn DeCarlo: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Brian Garvey: Series Designer/Book Layout

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Bruce Donnola: Photo Researcher

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Duignan, Brian, editor. | DeCarlo, Carolyn, editor.

Title: The U.S. Constitution and the separation of powers / edited by Brian Duignan and Carolyn DeCarlo.

Description: New York : Britannica Educational Publishing, in Association with Rosen Educational Services, 2019. | Series: Checks and balances in the U.S. government | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Grades 7-12.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781538301753 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: United States. ConstitutionJuvenile literature. | Separation of powersUnited StatesJuvenile literature. | United StatesPolitics and governmentJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E303.U836 2019 | DDC 342.73029--dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

Photo credits: Cover, p. 1 Jeff Overs/BBC News & Current Affairs/Getty Images (document), Lightspring/Shutterstock.com (scale), iStockphoto.com/arsenisspyros (capital); pp. 4-5, 113 National Archives, Washington, D.C.; pp. 6-7 Hulton Archive/Archive Photos/Getty Images; pp. 13, 21 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.; pp. 24-25 Comstock/Thinkstock; pp. 30, 67 Stock Montage/Archive Photos/Getty Images; p. 32 Corbis; pp. 36-37 Robert W. Kelly/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images; p. 38 George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress, Washington D.C. (digital file no. 19032); p. 41 Harry S. Truman Library/NARA; p. 42 Mario Tama/Getty Images; p. 44 Paul Schutzer/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images; pp. 45, 52, 54, 102 Bettmann/Getty Images; p. 47 Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; pp. 56, 104, 111 AP Images; p. 63 The Federalist (vol.1) and A MLean, publisher, New York, 1788, from Rare Books and Special Collections Division in Madisons Treasures/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; p. 73 Don Despain/MediaMagnet/SuperStock; p. 77 Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1942.8.34; p. 80 Laurence Saubadu/AFP/Newscom; p. 82 Thinkstock/Jupiter Images; p. 86 Photos.com/Thinkstock; p. 92 Corbis Historical/Getty Images; p. 97 Franz Jantzen/Supreme Court of the United States; p. 107 Hulton Deutsch/Corbis Historical/Getty Images.

CONTENTS

T he U.S. Constitution, which provides the principles of government for the United States, is a landmark document of the Western world. It is the oldest written national constitution in use. Adopted in 1789, the Constitution divides governmental authority between a central national government and various separate state governments. It defined the principal organs of government and their jurisdictions as well as the basic rights of citizens, but it was not, however, the first such document created for the task in the United States. Its predecessor, the Articles of Confederation, was a kind of template for the Constitution, providing the new nation with its first, instructive experience in self-government under a written document.

The Articles of Confederation, in force from 1781 to 1789, served as a bridge between the early government by the Continental Congress during the Revolutionary period and the federal system of government provided under the U.S. Constitution. Because the experience of overbearing British central authority was vivid in colonial minds, the drafters of the Articles deliberately established a confederation of sovereign states. Their intention is manifest in the name of the new nation, established in Article I: the United States of America. The Articles were written in 177677 and adopted by the Congress on November 15, 1777. However, the document was not fully ratified by the states until March 1, 1781.

An original copy of the U.S. Constitution is housed in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

On paper, the Congress had power to regulate foreign affairs, war, and the postal service and to appoint military officers, control Indian affairs, borrow and coin money, and issue bills of credit. In reality, however, the Articles gave the Congress no power to enforce its requests to the states for money or troops, and by the end of 1786 governmental effectiveness had broken down.

Nevertheless, some solid accomplishments had been achieved: certain state claims to western lands were settled, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 established the fundamental pattern of evolving government in the territories north of the Ohio River. Though on balance a flawed document, severely limiting the power of the central government, the short-lived Articles by their very weaknesses paved the way for the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and the present form of U.S. government.

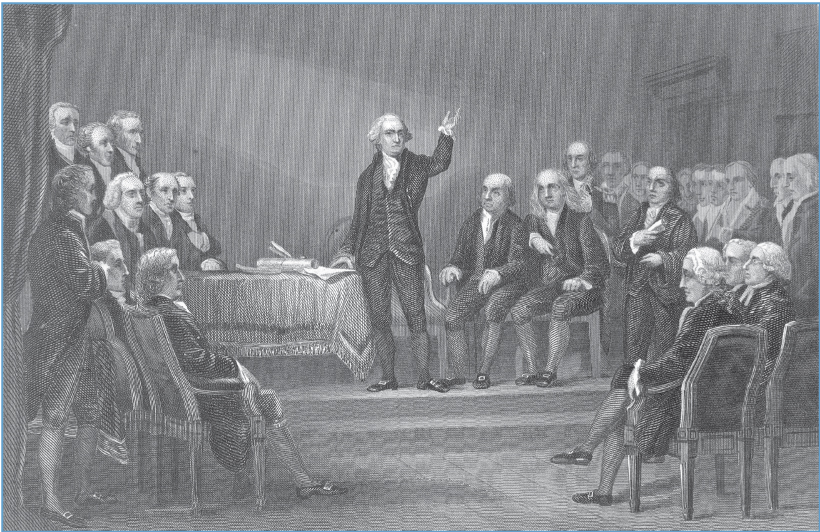

Future first President George Washington (178997) presides over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 1787.

The Constitution was written during the summer of 1787 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, by 55 delegates to a Constitutional Convention that was called ostensibly to amend the Articles of Confederation. The Constitution was the product of political compromise after long and often rancorous debates over issues such as states rights, representation, and slavery. Delegates from small and large states disagreed over whether the number of representatives in the new federal legislature should be the same for each stateas was the case under the Articles of Confederationor different depending on a states population. In addition, some delegates from Northern states sought to abolish slavery or, failing that, to make representation dependent on the size of a states free population. At the same time, some Southern delegates threatened to abandon the convention if their demands to keep slavery and the slave trade legal and to count slaves for representation purposes were not met.

Eventually, the framers resolved their disputes by adopting a proposal put forward by the Connecticut delegation. The Great Compromise, as it came to be known, created a bicameral legislature with a Senate, in which all states would be equally represented, and a House of Representatives, in which representation would be apportioned on the basis of a states free population plus three-fifths of its slave population. The new Constitution was submitted for ratification to the 13 states on September 28, 1787.

T he first constitution of the United States was known as the Articles of Confederation. The Articles were written in 177677, after independence from Great Britain had been declared and while the American Revolution was in progress. As a constitution, the Articles had a short life. The document was not fully ratified by the states until March 1, 1781, and it remained in effect only until March 4, 1789the date on which the present U.S. Constitution went into effect. Under the Articles, Congress was the sole organ of government.