Separation of Powers in the American Political System

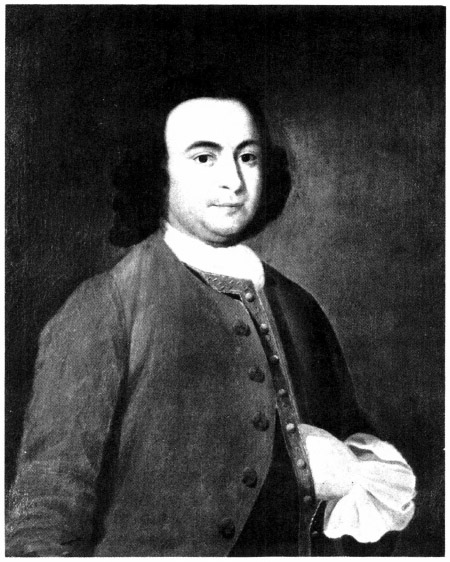

GEORGE MASON

Painted in 1811 by D. W Boudet, after a lost portrait by John Hesselius.

(Courtesy of the Virginia Museum, Richmond.)

Copyright 1989 by George Mason University Press

4400 University Drive

Fairfax, VA 22030

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

British Cataloging in Publication Information Available

Distributed by arrangement with

University Publishing Associates, Inc.

4720 Boston Way

Lanham, MD 20706

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU England

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Separation of powers in the American political system / edited by Barbara B. Knight.

p. cm. (The George Mason lectures)

Includes bibliographies.

1. Separation of powersUnited States. I. Knight, Barbara B. II. Series.

JK305.S48 1989 320.4'04'0973dc20 8911760 CIP AC

ISBN 0913969265 (alk. paper)

All George Mason University Press books are produced on acid-free paper which exceeds the minimum standards set by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.

Introduction

by

Barbara B. Knight

Associate Professor of Government George Mason University

Separation of powers is considered one of the most fundamental and unique of the American constitutional principles and at the same time seems to be one of the most misunderstood. Debate continues concerning the original nature and intent of this framework and whether or not the separation of powers as it currently exists in the United States government remains true to the original intent. Two persistent questions are: what is the relationship, if any, of American separation of powers to the older concept of mixed government and what is the connection between the governmental organization of separated powers and the political goal of checks and balances? Underlying both these questions is the basic issue of how the constitutional framers thought limited government and protection of liberty could best be achieved.

This introductory essay will approach these questions by examining important aspects of the theoretical and normative assumptions of the concept of separation of powers. The four essays which follow analyze contemporary separation of powers in the American political system from the perspective of the historical separation and of the place of each of the three branches of government, legislative, executive and judicial, within the overall framework.

In order to understand separation of powers as a means to limit government, particularly in its relation to mixed government and checks and balances, it is useful to begin by comparing and contrasting the conceptual models and normative assumptions from which they are derived.

The Early Development of the Concept of Mixed Government

The theory of mixed government seeks to allocate political authority on the basis of social classes, mixing within one government several types of government. Whatever form the mixture takes, all versions of the mixed regime have intended to create a balance to provide for political stability and to protect against abuses of governmental authority. Institutions, social classes and principles believed to be inherent within these classes were combined in the hope of achieving a judicious balance. Central to the balancing was the provision for law to prescribe the relationship of the classes within the constitutional structure and the role of each class within the governing process.

In contrast to the more modern concept of separation of powers, mixed government derives from classical Greek, Roman and medieval thought. In an early version, the mixture proposed in Platos Lawscombined monarchy and democracy. Aristotle presented the mixed regime, or polity, in the Politics as a solution to the problem of discovering the best practicable form of government. He sought to discover a regime in which justice could most fully be obtained, one in which the good man could also be a good citizen because of a coincidence of qualities that were both ethically and politically appropriate. In addition, he believed that this mixed regime would not deteriorate into a perverted form of government, since it was the pure form of government which eventually became perverted.

Aristotle claimed to have discovered a way for citizens to rule in the interest of all: a combination, or mixture, of two classes, oligarchs and democrats, the few rich and the many poor but free. Both classes and principles on which legitimate claims to rule are based, wealth and numbers, were thus combined within one government. A goal was to achieve political stability, halting the cycles of political decay. Power to govern was thus mixed, not divided, in this model.1

As Martin Diamond has pointed out, Aristotle believed that in this regime each class contained such radically different human elements from those in other classes that for stability the political system had to include their basic diversity. According to this arrangement each class possessed complete governing power. Each acted as if it alone had final political decision-making power and so could absolutely veto the other element. Hence, in mixed government there is no give and take of checks and balances in the way that this arrangement works within a separation of powers framework. In addition, each class was believed to contribute its particular and partial idea of justice to the benefit of the whole community.2

While Aristotle wrote of functions of government in the Politics, he did not conceive of these in terms of legislative, executive and judicial, the contemporary familiar trio. Instead, he described deliberative functions, those performed by magistrates, and those by judges. Nor were these functions parcelled out to distinct branches of government; magistrates and the assembly might share deliberative functions, for example.

In the Greek historian Polybius presentation of a mixed regime the tripartite combination clearly appears. Confronting what he perceived to be the natural cycle of constitutions, from kingship to tyranny, from aristocracy to oligarchy and from democracy to mob rule, Polybius proposed a solution based upon the Spartan model. The only way out of the vicious natural cycle of constitutional deterioration was to adopt a mixed regime combining monarchy, aristocracy and democracy.

It has been suggested that Polybius was the first to combine the concept of the mixed constitution, initially developed by Plato and Aristotle, with a division of power, new with his theory. Aristotle had combined oligarchy and democracy, two forms of government, by concentrating political power in the middle class. This was the group within the society which was believed to be the most moderate. Its members were neither very rich nor very poor and therefore could be counted on to enact only moderate measures. An aim of this regime was to achieve moderation within the government. Here, Aristotle believed, the good man could also be the good citizen.

Polybius mixture, as he attempted to diagnose the strength of Rome, consisted of elements of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. Each was to share in the power of the state as each was connected to a particular institution of government. Monarchy was linked to the consulate, aristocracy to the senate, and democracy to the assembly.3 It is instructive to note the importance of the division of legislative power into two parts, senate and assembly, here, since this early bicameral mixture points the way to the central role of the two-house legislature in the work of the eighteenth century Frenchman Montesquieu to achieve balanced government.