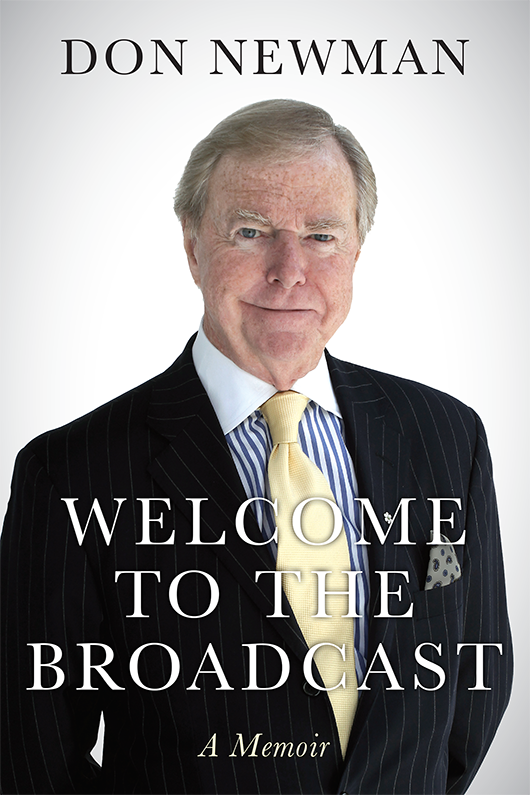

No Time-Outs in Politics

O UTRAGE COMES NATURALLY to him. But on the morning of Thursday, December 6, 2008, John Baird was ready to outdo himself.

We will go over the heads of MPs, we will go over the head of the Governor General We will go to the people, Baird fumed, telling me this face to face, one on one, on live television across the country.

The transport minister and I were in the foyer of the House of Commons, inside a small rectangle marked off by CBC camera crews and set up as an area for interviewing and reporting live to the CBC News Network. The atmosphere was electric. The foyer was full of reporters, camera crews and politicians.

Over the years, at different times, I had hosted a weekly and a daily political program from the foyer, and broadcast throne speeches, budgets and other big events from right outside the House of Commons chamber. But never had the atmosphere been like this. Because that morning, history seemed about to be made: for the second time since Confederation, it was likely that a government was going to be replaced after a non-confidence vote in the House of Commons without there first being a general election. And if that did happen, the new government was going to be in office for at least a year and a half. Only one thing could prevent that: the agreement of Governor General Michalle Jean to a request by Prime Minister Stephen Harper to end a session of Parliament that had only been running for two weeks, and leave a break before starting a new session.

We need a time-out, Baird said, and then claimed that was what Canadians in general wanted.

You get time-outs in football, I challenged him. This is politics, not football. There are no time-outs in politics.

While Baird and I were talking in the foyer, Stephen Harper was a couple of miles away at Rideau Hall, the Governor Generals residence, making his case for why, after beginning a new, first session of Parliament, he now wanted to end the session and take a break of almost two months.

How had we suddenly reached such a curious state of affairs? Harper and his Conservatives had blundered. In a financial update a few days earlier, Finance Minister Jim Flaherty had not only painted a financial scenario everyone knew was much too optimistic, but the Harper government had also announced it was planning to end public funding for political parties. The Conservatives could prosper without public funds. The Liberals, New Democrats and Bloc Qubcois could not.

Pretending that their own financial future was not their primary concern, the Opposition claimed it was concern for the economy that forced them to band together, agree to defeat the government in a non-confidence vote a few days later, and then present to the Governor General a signed agreement creating a LiberalNDP coalition government. The separatist Bloc Qubcois would not be in the government, but would support it on confidence votes for at least eighteen months, meaning the coalition would last at least a year and a half.

Only once before, in 1926, when Britain still sent governors general to Canada, had a request for an election coming from a prime minster defeated on a confidence vote in the House of Commons been refused. Lord Byng thought it proper that he first invite the Conservatives, led by Arthur Meighen, to try and win the confidence of the House, and said no to Liberal prime minister Mackenzie Kings election request. At the time, the Conservatives had more seats in the House of Commons than the Liberals, and King had been abandoned by his voting partners, the Progressives.

Byngs decision created a constitutional crisis in 1926. Now it seemed Canada was on the edge of another one. Would Michalle Jean agree to Harpers request to end the parliamentary session (known as prorogation)? And if she did not, and the Conservatives were defeated on a confidence vote, would she agree to the new election that Harper would obviously ask for? Or would she give the coalition the government?

All that was on the line as John Baird and I began our conversation, seen live across the country.

Baird was thenand still isthe governments designated hitter. Over six feet tall, burly, with a shock of hair cut short that apparently used to be red enough to earn him the nickname Rusty, his bellicose, loud and aggressive style of answering questions in the House of Commons has some reporters referring to him as Bombastic Bushkin. Away from the House, he is more genial. A bachelor, he often escorts the prime ministers wife, Laureen, to the National Arts Centre or other events in Ottawa.

In the foyer of the House that December 4, he was neither genial nor bombastic. He was determined. On a repetitive message track obviously worked out with the Prime Ministers Office, he kept pushing the idea that, in minority governments, coalitions are somehow illegitimate, and saying the Conservatives would go over the heads of Parliament and the Governor General, calling for a campaign of civil disobedience.

I was so amazed at this approach that at one point I told him: I cant believe it. You are a Conservative, in the British parliamentary system, and you want to go over the heads of MPs You are saying that MPs and the Governor General arent important.

Of course they are important. They are elected to come here and represent their constituencies, Baird responded, knowing full well that MPs come to Ottawa to vote their partys instructions and that the Governor General is appointed to exercise constitutional powers, not represent any constituents.

But they are not important if they dont do what you want them to? I inquired.

Baird then turned on what the Conservatives thought was the weakness of the coalition dealthe agreement of the Bloc Qubcois to support the LiberalNDP coalition on confidence votesalthough he claimed incorrectly, as others in his party did, that the separatists were actually going to be part of the government.

This, of course was wrong, and Baird knew it. Still, he said it because it was an argument that resonated with many Canadians outside of Quebec, even though it flew in the face of two facts. First, as Opposition leader following the 2004 election that put the Paul Martin Liberals into a minority, Stephen Harper had signed a similar letter with the same leaders of the Bloc and the NDP to make an arrangement for a coalition government after a Liberal confidence defeat. And second, as a minority government, the Conservatives had a number of times stayed in power only because they were supported in confidence votes by the Bloc Qubcois.

So, with that in mind, I asked Baird, Does that mean if your government remains in power and you bring in a budget, and if that budget passes, but only with the votes of the NDP supporting you, it will be an illegitimate budget?

It will be a budget with a maple leaf on it, he quickly countered, completely ignoring the point because he couldnt answer it.

Baird also obfuscated on how the Conservatives would go over the heads of Parliament and over the head of the Governor General. But since government supporters were already demonstrating outside of Rideau Hall while Harper was meeting inside, I had some idea of what he had in mind. I recalled demonstrations in Ukraine a few years earlier that had overturned the results of an election.