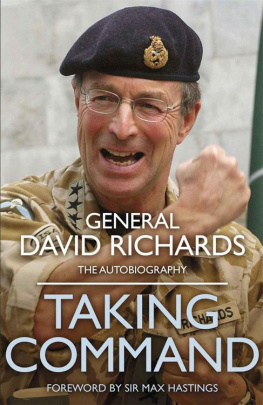

PROLOGUE

BREAKFAST WITH THE PM

It was a Saturday morning in early December in Ottawa and I was late. Again. Not a good start to a job interview with the Prime Minister of Canada.

The interview was to determine if I was to become the next Chief of the Defence Staff. The process had commenced in the fall of 2004, when Eugene Lang, Chief of Staff to Minister of Defence Bill Graham, approached me in the last week of November and asked, on the Ministers behalf, whether I wanted to be considered for the Chiefs appointment.

I had met the Minister several times, had briefed him extensively on the situation in Afghanistan immediately after I relinquished command of the NATO mission in Kabul (the International Security Assistance Force, or ISAF) and had travelled with him to Quito, Ecuador, to participate in a Defence Ministers of the Americas conference. During that trip we had discussed, in some detail, the state of the Canadian military, the kind of forces needed for the threats we faced and the changes we would have to begin to launch us on the road to building those forces. I had drawn a series of diagrams to illustrate my ideas during the six-hour flight to Quito, and we chewed over many of the problems those necessary changes would both cure and cause.

I had come to appreciate the tremendous character that Graham brought to his appointment, and we had certainly established a rapport early during his tenure as Minister. We were comfortable with each other, we spoke frankly and both of us enjoyed the funnier side of events and focused on the serious issues as well. I was confident that if I did become Chief, he and I would work well together.

My response to Genes approach was pretty quick and, I thought, clear. Yes, I was willing to throw my hat into the ring, but even if the government offered me the job and the promotion to full general that followed, I would not necessarily accept it. In short, I told him that if I was to take the job, it had to be a two-way contract, with direct support from the Prime Minister, the Minister of Defence and the entire Cabinet. They also had to commit to financial support in future federal budgets for the changes I wanted to introduce. I was not about to take on responsibility for the enormous changes that the Canadian Forces required on my own. I truly believed that all Canadians had to be a part of this rebuilding of their armed forces if it was going to be successful. Our business involved putting men and women in areas of high risk, from the high seas to search-and-rescue missions to combat operations in faraway lands, so once we started down that road of change we could not afford to fail.

The first step in the process of selecting the new Chief was an interview with the Minister, with Gene present as well. I knew that at least five other officers, including one recently retired general, were also being considered and that there was considerable support for some of them within military and government circlesand little for me. Part of the reason was a memorandum that I had written to the current Chief of the Defence Staff, General Ray Henault, a few months previous, that had not made me popular. I had suggested that the Canadian Forces focus on coherently and cohesively delivering a strong punch in limited geographical areas while concentrating on major centres of population both in Canada and overseas. The memo had been widely distributed (one of my first lessons on how leaky National Defence Headquarters was) and had found its way to the media. That memo had engendered much backlash and emotion, not so much because of what it said as because of what many people, in our survival mentality, read into it.

In the backwards-looking, bureaucratic, cumbersome and risk-averse Canadian Forces that we had become, no one encouraged the ability to work as one organization, and any suggestion of strategic change was fought tooth and nail by almost all concerned. I wrote the memo out of frustration that the Canadian Forces did not appear to know where it was going, and with fear that catastrophic failure was looming for all of us. My words, however, were used to paint me as a narrow-minded, land-oriented army officer who would use any increases in the defence budget to rebuild the army at the expense of the navy and air force. There was, therefore, much nervousness in military circles at the prospect that I would be chosen as the new Chief, a position that some presumed I would use to promote only the land component of the Canadian Forces. There was also some nervousness elsewhere that I would be impossible to control if appointed as the senior military officer in Canada.

The interview was scheduled for 4 p.m. on November 23, 2004, immediately following that days parliamentary session, in Bill Grahams office. Since the selection committee was working in confidence to keep speculation to a minimum, essentially all I was told was the date and time of the interview. My office as army commander was on the nineteenth floor of National Defence Headquarters, in the centre of Ottawa, and the Ministers was directly beneath me on the Executive Floor (which happened to be the thirteenth floor but was never referred to as such, whether out of tradition or superstition I was never sure). I planned to be there right on time and came off the elevator at the Ministers floor about one minute before the scheduled interview. It was only then that I was told that the meeting was scheduled for the Ministers parliamentary office, in the Centre Block on Parliament Hill. Fortunately, the corporal who was Grahams driver was on hand and immediately offered to drive me over to the Centre Block and escort me through the time-consuming rings of security, a necessary evil in government buildings. Still, I was thirty minutes late for my first interview as a potential CEO. In an organization in which punctuality and timeliness are virtues, this was clearly not a good start.

The interview, however, went fine; it wasnt a great job interview, but it wasnt a bad one either. In Grahams badly lit office, equipped with the most uncomfortable chairs imaginable and in the depressing darkness of an early Ottawa winter, we discussed the potential missions for the CF, international and domestic, the changes needed to execute those missions successfully, the importance of international relationships, particularly those within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and our relations with the United States and other allies. I think Graham had already perceived my enormous disdain for the inept and inflexible institution that I believed that NATO, the Western military alliance, had become since the end of the Cold War. I didnt hold back, and told him as clearly as I could what I believed had to be done and why, what the priorities had to be and what it would all cost. Gene Lang took some notes and did not say a word.

The last item we discussed was my idea of a two-way contract. Clearly, Gene had passed this on to Graham, and the Minister seemed intrigued. What did I mean by that? he asked. I explained, again, that it was pointless to ask any one person to take on the task of making changes of such magnitude and importance, and that if we tried to put it on one persons shoulders, we could expect failure. A Chief of the Defence Staff without clear government support in the form of actions, not just speeches and policy statements, was doomed to preside over an organization on its way to irrelevance, just as the country needed us most. As Walt Natynczyk, my eventual successor as Chief, used to say, the Canadian Forces had become a self-licking ice cream cone, too big to be cheap and too small to do much more than administer itself. I had no intention of presiding over that kind of army, navy and air force and told Graham so. I said that if the Government of Canada wanted to do something for its armed forceshopefully, changes along the lines of what I had proposedthey might want to consider me as one of the candidates for Chief of the Defence Staff. If not, I told him, I was clearly not their man and had no interest in the job.