I n early 1991 I stood on a platform just north of Fort McMurray, Alberta, and surveyed what I suspected would mark the end of my career in the petroleum industry.

I was staring at an essentially malfunctioning industrial plant located in a stretch of northern boreal forest extending as far as the eye could see in every direction. The wilderness had a kind of majestic beauty often associated with the North, and it served as home to a few thousand First Nations residents, along with black bear, moose, beaver and various predators. The land had been carved and irrigated for millions of years by the Athabasca River, which originates in the Columbia Icefield within the Canadian Rockies straddling the continental divide and meanders north, eventually joining the Mackenzie River on its way to the Arctic Ocean.

The landscape was gently rolling, almost flat. There is a magnificence about such vast open country, even when it lacks dramatic landmarks, but this area appeared destined to remain unknown and unexplored, save for the bands of First Nations who have survived its harsh climate for a millennium or two. Lacking both mineral resources and tourist appeal, the land had little to offer the world beyond a habitat for those First Nations people and the fish and wildlife that sustained them. With one enormous exception.

Beneath the surface was an estimated 1.8 trillion barrels of crude oil, making it the largest resource of its kind in the world.

Unlike virtually all the other sources of petroleum tapped throughout the globe since the first commercial oil well was drilled in 1853, this did not await discovery and drainage like some massive subterranean swimming pool. The petroleum is suspended for the most part in a blend of sand, clay and water below ground and beneath a covering layer of shale. And its not even petroleum as we know it. It looks nothing like the amber-coloured, easily flowing oil that you may see being poured into your cars engine, or even the black gold spewing from the gusher oil wells depicted in movies.

In fact, its not oil. Its bitumen, a sticky black substance with the characteristics of thick, cold molasses. The nearest youre likely to get to bitumen in its raw form is when you drive on asphalt roads; asphalt is composed of bitumen that has been heated and mixed with fine gravel.

First Nations people encountered bitumen seeping out of the ground in various locations throughout this section of northern Alberta at least a thousand years ago, and they made practical use of it, applying the more fluid sources to the seams of their canoes to seal them from water. They also discovered that burning the substance in pots created a smudge to ward off the hordes of black flies and mosquitoes that clouded the skies.

These massive reserves of bitumen make up Canadas oil sands,Russia, Africa and the Middle East. The dream of recovering oil from Alberta bitumen on a commercial basis was born in the 1900s, when John D. Rockefeller was building Standard Oil into the giant that we now know primarily as ExxonMobil. (Standard Oil was broken into several companies in 1911.) The most appealing feature of the oil sands was the fact that they were there to be taken. Instead of cruising the world in search of oil hidden beneath ground and drilling ten dry wells for every one that proved successful, why not focus on the largest known source of oil?

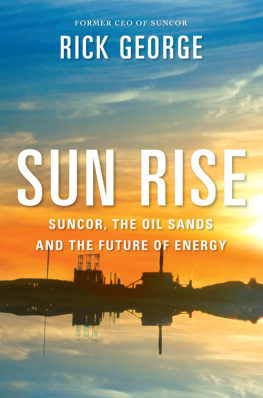

A lot of minds went to work on the idea over the years. A lot of money was spent to make it happen and a lot of companies invested millions of dollars in the dream. One of them was my employer at the time, Sun Oil, which began processing bitumen from the oil sands in 1967. After more than twenty years of unproductive effort, Sun recruited me to make the oil sands work where those before me had failed, although thats not how my assignment was viewed by others. Failure had been so deeply ingrained in the company over the years that many employees suspected I had been tapped to shut down the project entirely and cut Suns losses.

I could have turned down the job. In fact, there were times during my first few years in Canada when I wondered why I hadnt turned it down.

I had already achieved more than I envisioned for a guy from Brush, Colorado, population around five thousand people with maybe an equal number of cattle and horses. When the job offer arrived I was living in London, England, with my familywife, Julie; sons Zachary and Matt, thirteen and ten, respectively; and five-year-old daughter, Emily. We had been in Britain, moving between London and Aberdeen, Scotland, for ten years and, after something of a cultural adjustment, enjoying it. I was in charge of Sun Oils international operations on the upstream side, which included exploring for oil, developing reserves, producing the oil and transporting it to the customer. My responsibilities included operations in the North Sea, the Middle East and a few other regions beyond North America.

I enjoyed my work. At age forty I had spent my entire working life, including high school summer jobs, in the petroleum industry. Living in London with a young family, relatively free to make major decisions far from the interference of head office back in Philadelphia, I was satisfied with both my life and my career. Julie and I took our children for vacations in Europe, where we treated them to sights, cultures and experiences that enriched their lives as much as they did ours. London remained one of the worlds great vibrant cities, and the international petroleum industry was growing more dynamic in its range and challenges with every passing year. Alberta was not only far away geographically; it was far from my mind as well.

Yet as much as I find satisfaction in my work, I also enjoy tackling new challenges. In my position in London, these were as small as making a personnel change and as massive and complex as supervising the design and installation of the worlds first purpose-built floating production vessel to tap North Sea oil, a project that proved exceptionally successful and earned me the position of running Suns international operations.

When Tom Thomson, CEO of Suncor, Sun Oils Canadian arm, asked me to consider coming to Canada as his appointed successor, I had one reasonI was comfortable and settledfor saying no. I had two reasons for at least giving it consideration. One was Tom himself, a cultured man with high integrity and admirable values, whom I liked personally. His request was even more persuasive because I knew Tom was suffering from terminal cancer, and my selection would probably be his last major management decision.

The other reason was my inclination to look for new challenges. Taking over the reins at Suncor would mean making its oil sands operations profitable, something no one had managed to do so far. I suspected it would be the most demanding task I had ever assumed, and my optimistic outlook made me believe I could succeed.

Im no Pollyanna, but whenever Im faced with a problem, I tend to focus on the positive side rather than evaluating all the things that may go wrong. On the scale of the old Is the glass half empty or half full? clich, I tend to consider the glass completely full. This has inspired a lot of kidding from my children, who say Im the most optimistic person theyve ever known.