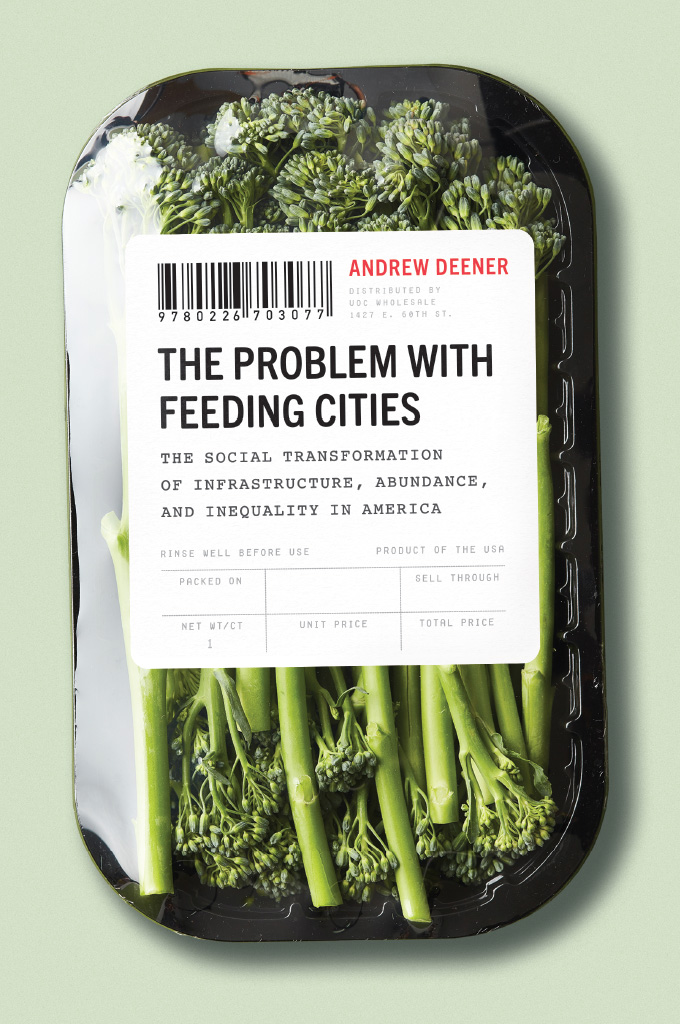

The Problem with Feeding Cities

The Problem with Feeding Cities

The Social Transformation of Infrastructure, Abundance, and Inequality in America

Andrew Deener

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-70291-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-70307-7 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-70310-7 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226703107.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Deener, Andrew, author.

Title: The problem with feeding cities : the social transformation of infrastructure, abundance, and inequality in America / Andrew Deener.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020008790 | ISBN 9780226702919 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226703077 (paperback) | ISBN 9780226703107 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Food supplyUnited States. | Food securityUnited States. | Food consumptionUnited States.

Classification: LCC HD9005 .D37 2020 | DDC 338.1/973091732dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020008790

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Alana, Azalea, and Echo

Contents

My family visits the same supermarket every week and purchases many of the same products on each visit. We keep a list on our phones to remind us of the things we want to replace. We also think about the week ahead as we search through the aisles and make our choices. What special ingredients are necessary for dinners during the weekdays, what do our kids want as snacks, and what will they bring to school for lunch?

As we make our selections, we look at the prices of comparable products. For some of the packaged goods, we look at the ingredients too. We evaluate the color and texture of the fresh foods in front of us. We rarely find something so unfamiliar that we have not seen it before. More often, we find a twist on an already established product that we try outa new cereal or a different apple variety. We pile the stuff into our shopping cart. It is an exercise of mundane knowledge: recognizing whether the lettuce looks wilted; understanding how the aisles are organized so we can find the exact products and brands; unloading the objects from the shopping cart onto the conveyor belt at the checkout station; paying with a debit card that automatically transfers money from our bank account to the stores account; and bagging up the groceries to take home.

When we explore the sea of products found throughout the aisles, we do not think about how or why all those items are there with such reliability. For most of us, the supermarket is just there, filled with all the stuff we are looking for. This book is, in part, about how that remarkable system of abundance and convenience came into beingthe social organization of a high-volume and high-variety market infrastructure.

Yet the rise of this kind of vital infrastructure has also created unexpected consequences. When I started conducting research in Philadelphia in 2010, I met Cynthia Watson, a woman in her early sixties, who has lived in various West Philadelphia neighborhoods for most of her life. The neighborhood where Cynthia currently resides has dozens of vacant lots and poor housing conditions. As a young black girl growing up in this segregated city, Cynthia walked to a range of nearby shops: a green grocer owned by one of her neighbors and an independently owned grocery store and pharmacy. All of that commerce is gone. The only food shopping option in walking distance from her home is a corner store.

The small shop on Cynthias block is packed from floor to ceiling with chips, soda, candy, cereal, bread, diapers, cleaning supplies, and other household items. The couple that owns the store tried carrying different fruits and vegetables to fulfill requests of some residents. They purchased cases of bananas, apples, and oranges, and sometimes avocados and potatoes, at a wholesale market. However, difficulties mounted up. Without proper refrigeration or quick turnover, they could not sell most of the product before it rotted. While some residents, like Cynthia, purchased the fresh produce on occasion, the price point was higher than at supermarkets, variety and choice were much more limited, and the quality was poorer.

However, the problems facing this neighborhood and its residents are more complicated than inadequate food shopping options. Cynthia helps to support and feed her grandchildren, preparing most of their dinners. With limited economic resources, she and her family rely on her churchs food cupboard for canned vegetables, boxes of rice, and loaves of bread sent over from Philabundance, the citys food bank. For other foods, Cynthia takes a train, bus, or sometimes a taxi several miles to the Reading Terminal Market, the famed vending market and one of Pennsylvanias largest redeemers of Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, formerly called food stamps. There, Amish bakers and local sandwich-makers sell their specialties alongside fish mongers, Italian butchers, and discounted produce stalls.

My experience and Cynthias experience represent different sides of the food distribution equationone side defined by abundance and convenience, the other by economic insecurity, limited transportation options, and lack of accessibility. Yet the more I learned about healthy food access and local responses to it, the more I questioned whether my starting point in neighborhoods was the right choice for understanding the problem. Even though abandoned properties and a lack of grocery stores are visible indicators of racial and economic disparities throughout Philadelphia, healthy food access is a broader national and global problem related to building the vital infrastructure.

Rather than continuing on this track of how people live, shop, and eat in the city, I started seeking out different parts of the food system to better understand their interconnections. I investigated how markets and cities were developed, how distribution relationships between production, storage, transport, and consumption were constructed, how organizational actors coordinated and evaluated food supplies, and how these factors contributed to problems like limited access to healthy food, disruptions of market abundance and convenience, and the entanglements between the prominent market dynamics and the nonprofit organizations managing food insecurity.

Figuring out how an infrastructural system fits into or excludes the local environment was one part of my investigation. But I also wanted to trace the infrastructure backward in time to better understand how different food varieties and qualities were made into high-volume supply chains. The history of industrial food processing built on staple commodities was well documented, but it was less clear how perishable foodsthose that public health officials and nutritional experts deemed the healthiest, like fruits and vegetablesbecame incorporated into the infrastructure of mass consumption. My hunch was that if the policy concerns about food access were really about access to healthy food, then it was necessary to trace the historical links between the healthiest foods and the mass-merchandising system.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).