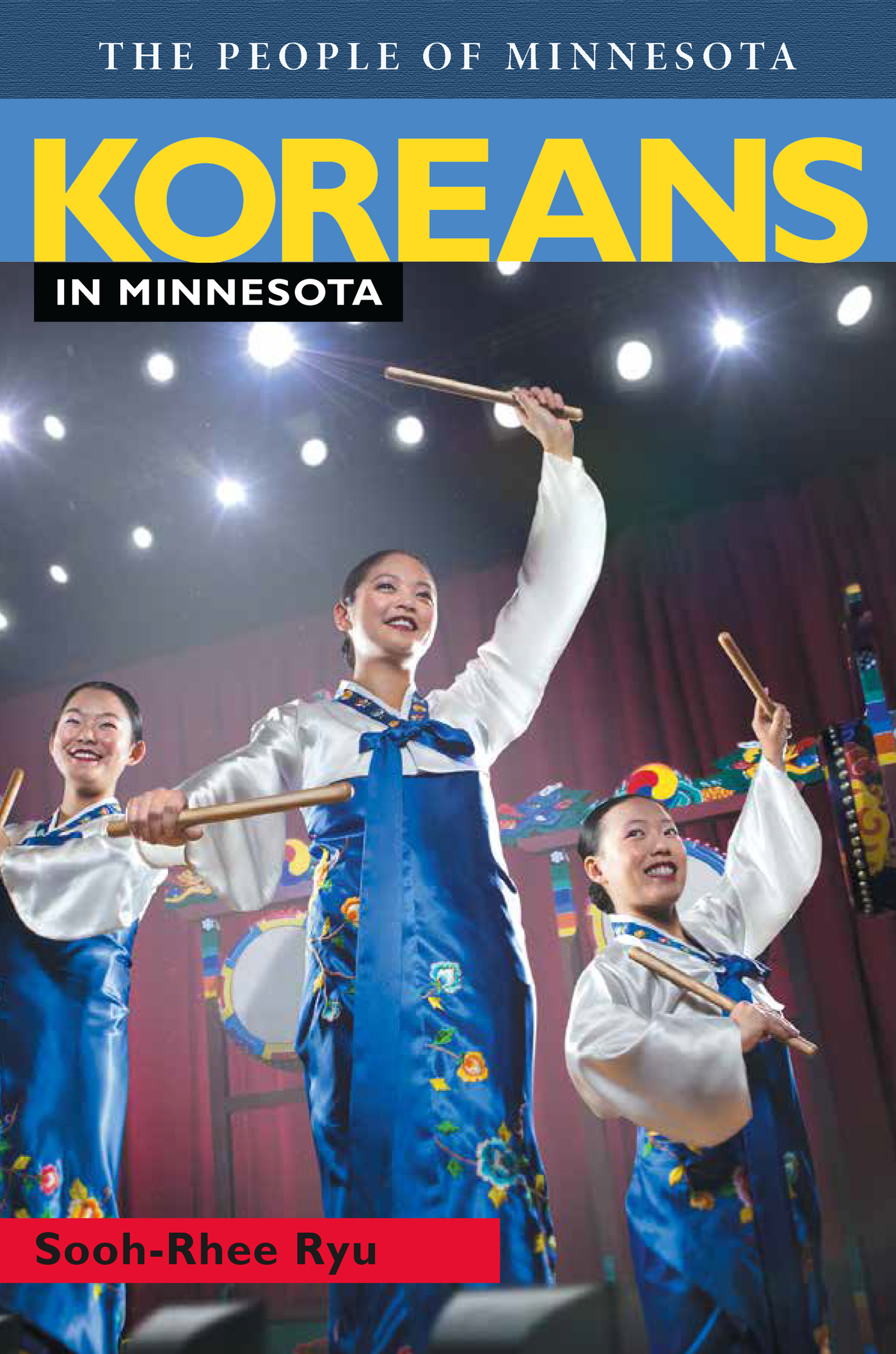

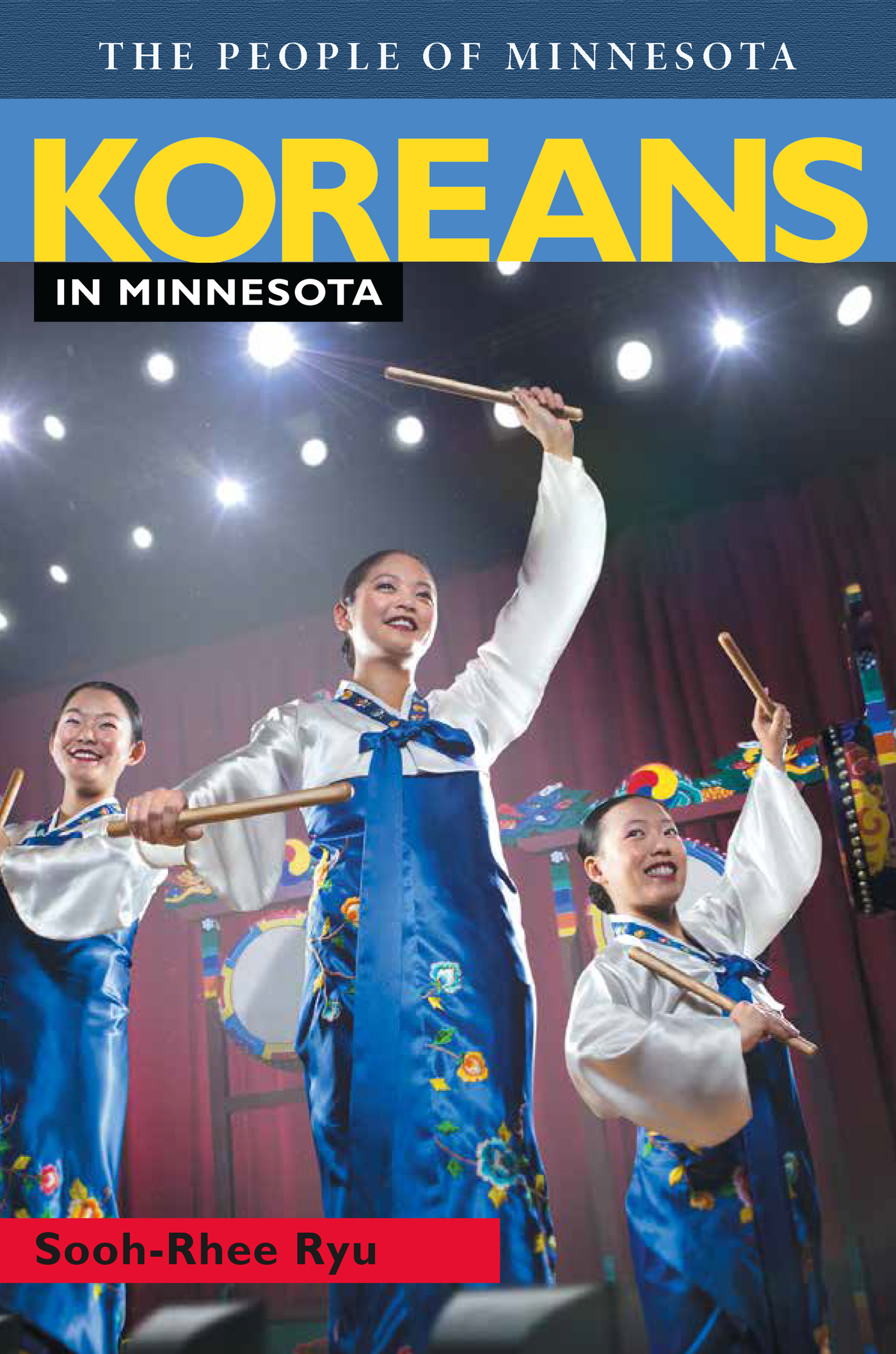

THE PEOPLE OF MINNESOTA

Koreans

IN MINNESOTA

Sooh-Rhee Ryu

Copyright 2019 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 55102-1906.

mnhspress.org

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN: 978-1-68134-133-0 (paper)

ISBN: 978-1-68134-134-7 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ryu, Sooh-Rhee, 1979 author.

Title: Koreans in Minnesota / Sooh-Rhee Ryu.

Description: St. Paul, MN : Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2019. | Series: People of Minnesota | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019019604 | ISBN 9781681341330 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681341347 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: KoreansMinnesota. | Korean-AmericansMinnesota. | ImmigrantsMinnesota.

Classification: LCC F615.K6 R98 2019 | DDC 977.6/1004957dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019019604

This and other Minnesota Historical Society Press books are available from popular e-book vendors.

Front cover: Photo by Kevin Kamen

Back cover: Photo by Stephen Wunrow

Cover design by Running Rhino Design.

Book design and composition by Wendy Holdman.

Contents

Koreans

IN MINNESOTA

From early arrivals who laid the groundwork for a Korean community, to Korean adoptees exploring their identity and finding friendship, to Korean women immigrating with their American husbands and adjusting to a new way of life, to so many others experiencing everyday joys and struggles, Koreans in the North Star State have many stories to tell. With more than twenty thousand Koreans living in Minnesota, and close to one and a half million in the United States, Koreans are a vibrant part of Americas colorful cultural mosaic.

Korean Immigration to the United States

In 2003, Korean Americans celebrated the hundredth anniversary of Korean migration, marking the 1903 arrival of the first Korean plantation workers in the Hawaiian Islands, then a US territory. Today, Koreans are the fifth-largest Asian group in the United States, comprising almost ten percent of the Asian population. As Koreans continue to settle in the land of opportunity, many different stories have led them to cross the Pacific Ocean.

The First Wave (19031905): Hawaii Pineapple and Sugar Plantation Workers

In the late nineteenth century, foreign powers such as the United States, Russia, and Japan put the empire of the Chosun dynasty (13921910) under great pressure to modernize. Then, turbulent political times and a nationwide famine brought great hardship to many ordinary Koreans. Given the opportunity to find employment in Hawaii, the first Korean immigrants mustered the courage to voyage to America. Between 1903 and 1905, eleven different ships made sixty-four voyages to Honolulu with Koreans on board.

The first wave of Korean immigration during this time consisted of 7,226 Koreans, including 637 women and 541 children. The S.S. Gaelic carried the first 102 Korean migrant workers (including twenty-one women and twenty-five children), who would make up for a labor shortage on Hawaiis pineapple and sugar plantations. Yankee planters had begun sugar production in Hawaii in the 1830s but struggled to recruit enough native Hawaiians to work the plantations. Since the 1850s, the Royal Hawaiian Agricultural Society had been recruiting Chinese migrant workers to fill the need for foreign labor; they began to bring in Japanese workers in 1868.

Hawaii was annexed to the United States in 1898 and was made a US territory two years later, at which point the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) made Chinese laborers illegal in Hawaii. The plantation owners encountered a major labor shortage. While Japanese workers became the main workforce in the plantations, they also tended to strike frequently. As a result, the Hawaiian government started to actively recruit Korean workers.

The Korean migration to Hawaii was largely the result of the efforts of Horace Newton Allen, an American Protestant missionary to Korea. Allen acted as an intermediary to convince the Korean king to send Koreans to Hawaii to strengthen relations with the United States. Allen published advertisements recruiting Korean workers in the Hwangsung newspaper. This effort to send Korean workers to the United States was facilitated by David W. Deshler, an American who was looking for business concessions in Korea and recognized the importance of Allens political capital. As a partner of the American Trading Company in Korea, Deshler helped build local offices in major Korean ports to recruit workers nationwide.

These early immigrants to Hawaii were mostly both farming and non-farming workers. A few were former soldiers, policemen, and woodcutters from cities in the northwestern province of Korea, and a small number were students who hoped to save enough from the plantation wages to continue their studies in the United States. But not all worked on the plantations. About seven thousand Koreans were scattered among different islands, and many worked in Honolulu as clerks, gardeners, cooks, and grooms and in other positions where the pay was steady.

Most of them were Christians, some coming to Hawaii for religious freedom as well as for a better economic life. American Presbyterian and Methodist missionaries had

The work conditions on the plantations were difficult. Korean laborers worked more than ten hours a day to earn seventy-five centsabout sixteen dollars a month. Within twenty-five years, 90 percent of the Korean workers left the plantations and found work in non-farming jobs, as shopkeepers, peddlers, and restaurant workers, for example.

But the influx of Korean migrant workers did not last long. After defeating Russia in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, Japan made Korea a protectorate, shaping its governments major policy decisions. The Japanese halted Korean workers emigration to protect their own laborers in Hawaii.

In addition to the sugar plantation workers, eleven hundred Koreans were brought to Hawaii as picture brides between 1910 and 1924. Most of the Korean laborers were single men between the ages of twenty and thirty, creating a gender imbalance that inspired these arranged marriages, made through the exchange of photographs.

These picture brides were mostly daughters of poor families in farming villages, their marriages arranged by an elder in their family. Matchmakers were also involved, many of them female relatives from the brides home village. Other brides had their own reasons to move to Hawaii, such as to escape poverty and patriarchy. The picture bride system was supported by the plantation owners, who expected the male laborers to settle down once they had started a family.

Most Korean picture brides were Christians; some were educated in American missionary schools before coming to Hawaii. Usually Korean picture brides had group marriage ceremonies at the First Korean Methodist Church in Honolulu alongside those who had arrived on the same ship.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.