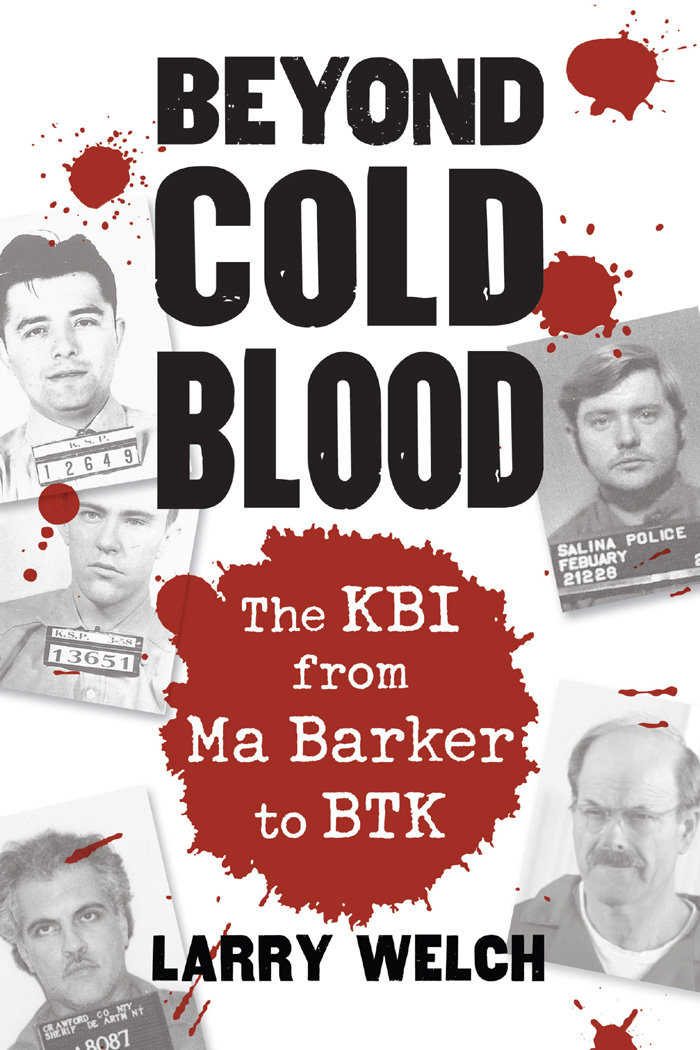

Beyond Cold Blood

Beyond Cold Blood

The KBI from

Ma Barker to BTK

Larry Welch

University Press of Kansas

2012 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Welch, Larry.

Beyond cold blood : the KBI from Ma Barker to BTK / Larry Welch.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7006-1885-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7006-2016-6 ( pbk : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2057-9 (ebook)

1. Kansas Bureau of InvestigationHistory. 2. Law enforcementKansasHistory. 3. CriminalsKansasHistory. I. Title.

HV8145.K2W45 2012

363.2509781dc23

2012016528

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481992.

The wicked flee when no man pursueth,

but the righteous are bold as a lion.

Proverbs 28:1

To all the lions and Shirley

Contents

Preface

The Kansas Bureau of Investigation (KBI) is a collection of fewer than 300 professional men and women positioned across the state of Kansas to serve the criminal justice systems of both the state and nation. They are assigned to nationally accredited forensic laboratories in Topeka, Kansas City, Pittsburg, and Great Bend; field offices in Overland Park, Great Bend, Wichita, and Pittsburg; or the headquarters in Topeka. They are ordinary men and women who do extraordinary things in pursuit of criminal justice, as others before them have done since 1939.

I have always believed that leadership is best defined as the privilege of directing the actions of others, with the emphasis on privilege. No better example of such privilege exists than the directorship of the KBI. From July 18, 1994, when I was appointed the tenth director of the KBI by Kansas Attorney General Robert Stephan, until June 1, 2007, when I retired as the second-longest-serving KBI director, four attorneys general and almost thirteen years later, that great privilege was mine.

Collectively, my nine predecessors and I served fourteen attorneys general. The KBI continues to be a unit of the office of the Kansas attorney general, as it was in 1939, and the director continues to serve at the pleasure of the attorney general, as he did in 1939. Attorney General John Andersons only instruction to Logan Sanford, when in 1957 he asked the agent to step up to director and move to Topeka was, You take over. You run it. If I have any objections, Ill let you know. That simple admonition has characterized the relationship between the attorney general of Kansas and the director of the KBI from 1939 to the present day. There has never been a signed contract between the two offices, and there has never been any guarantee of longevity for the director. There has always been a simple oath of office, a handshake, and subsequent confirmation by the Kansas senate.

Often understaffed, underfunded, undersized, and overassigned, the significant contributions of the KBI to the criminal justice system, state, and nation have always been disproportionate to the size of the agency. That was true in 1939 when the entire staff consisted of one director, nine special agents, and one secretary. It remains equally true today with the larger, but still insufficient, staff.

Despite a proud, scandal-free record of exceptional achievement in criminal justice and dedicated service to Kansas prosecutors, law enforcement, and crime victims and their families, no one has attempted to write a history of the KBI for public consumption. The closest effort was an internally prepared publication commemorating the agencys first fifty years, 19391989, printed in 1990 and distributed almost exclusively within the KBI family. In Cold Blood, Truman Capotes best seller, tells the story of one chapter in the KBIs history, an iconic chapter but nonetheless only one. The same can be said of KBI involvement in the infamous BTK case. Much has been written about the investigation to identify, apprehend, and prosecute Dennis Rader for the serial murders of ten citizens of Wichita from January 1974 to January 1991, and the KBIs proud participation in the Wichita Police Departments BTK Task Force, March 2004 to August 2005. Again, an essential chapter in KBI history, but merely one chapter in that story. Indeed, not a single KBI director preceding me wrote anything resembling a public memoir about his tenure. This book, then, is intended as an effort to reveal more of the history of a deserving agency.

The KBI has never been more important to the Kansas law enforcement community or the Kansas criminal justice system than it is today. The Kansas Law Enforcement Training Center, repository for Kansas law enforcement training records, reported on January 19, 2011, that 72 percent of all municipal and county law enforcement agencies in the state had ten or fewer full-time officers and that 50 percent had five or fewer full-time officers. Reliance on KBI resources, meager though they often are, necessarily follows.

Todays KBI employees are not dissimilar to their 1939 predecessors. They share a common mission: Dedication, Service, Integrity, the motto that has always adorned the beautiful KBI seal. The KBI has always striven to provide service to the law enforcement community and the criminal justice system with dedication and integrity. Excellence has remained the goal, and justice, not just prosecution, the objective.

As noted, the KBI began with just ten men and that would remain the number of agents for several years. Why ten? Probably for budgetary reasons, as well as a reflection of the reluctance of the legislature to create the agency in the first place. Perhaps, too, it was because another law enforcement agency with which the KBI was compared frequently at the time of its creation and in the years since, the Texas Rangers, also began with ten men. That, however, was in 1835, and the targets in that time and place were of the Apache and Comanche variety, not the gangsters, bootleggers, bank robbers, motorized cattle rustlers, and general lawlessness of the 1930s. Indeed, the creation of the KBI followed nearly a decade of lobbying efforts by the Kansas Bankers Association, the Kansas State Peace Officers Association, and the Kansas Livestock Association. Prior to 1939, law enforcement jurisdiction ended at the city limits and the county lines, and all responsibilities ended at the state line. The agencys creation changed that culture.

Born in that narrow corridor of time between the Great Depression and World War II, the bureaus earliest assignments reflected the interests of its original sponsors and the needs of the time: bank robberies, homicides, gangster activities, livestock theft, especially cattle rustling, and narcotics. Yes, narcotics, even then.

Over sixty years later, when I retired, the KBIs priorities, investigative and forensic, included narcotics, especially methamphetamine; violent crime, especially homicide and rape; and cyber-crime, especially child pornography and identity theft.