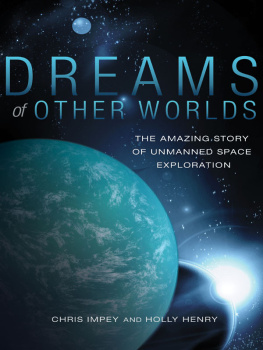

UNMANNED SPACE MISSIONS

AN EXPLORERS GUIDE TO THE UNIVERSE

UNMANNED SPACE MISSIONS

EDITED BY ERIK GREGERSEN, ASSOCIATE EDITOR, ASTRONOMY AND SPACE EXPLORATION

Published in 2010 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2010 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2010 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Erik Gregerson: Associate Editor, Astronomy and Space Exploration

Rosen Educational Services

Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Nicole Russo: Designer

Introduction by Corona Brezina

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Unmanned space missions / edited by Erik Gregersen.1st ed.

p. cm.(An explorers guide to the universe)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-052-5 (eBook)

1. Space probesPopular works. 2. Space flightsPopular works. I. Gregersen, Erik.

TL795.3.U56 2010

629.43'5dc22

2009036103

On the cover: The ability to collect samples and take photographs in inhospitable environments makes unmanned spacecraft, such as NASAs Mars rovers, highly valuable when exploring the universe. AFP/Getty Images

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

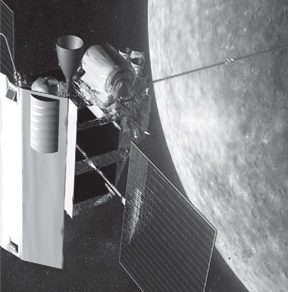

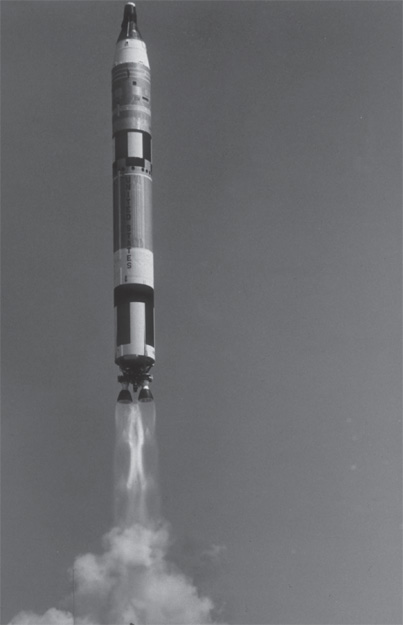

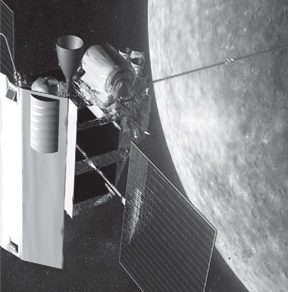

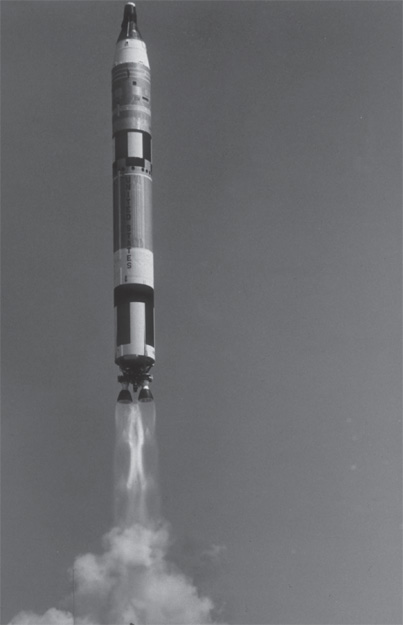

The development of rocket launchersa later version of which propelled this United States Gemini missionmade sending unmanned spacecraft into orbit a reality as early as the 1950s. Space Frontiers/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

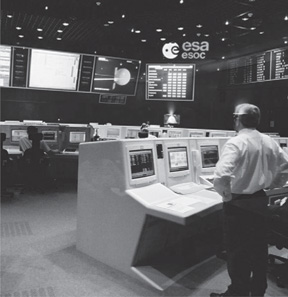

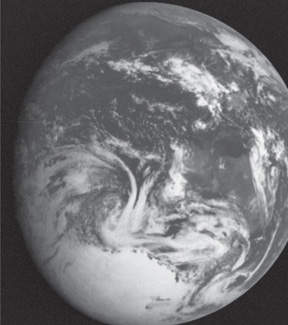

C urrent estimates indicate there are more than 900 functioning satellites orbiting Earth, collecting information and improving telecommunications around the globe on a continuous basis. In a way, these satellites are the enduring legacy of all the unmanned space missions that have come before, when humans sent technology out into the universe in their stead.

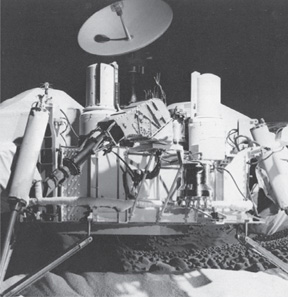

This book examines unmanned space missions, from the launching of the former Soviet Unions Sputnik in the 1950s to the extensive exploration of the solar systems planets conducted by Voyager spacecraft and the Mars Exploration Rovers. These pages describe the history of unmanned spaceflight, speculate about what the future holds, examine the scientific and practical applications of unmanned spaceflight, and profile some of the missions that have been launched into Earths orbit and that have navigated the solar system.

The story of unmanned spaceflight begins with the fundamental achievement of transporting a craft into Earths orbit, beyond the pull of gravity. There is only one vehicle that delivers the necessary thrust and that also operates both in the atmosphere and in spacethe rocket. The first rockets were fired by the Chinese in the 13th century. Rocketry was later refined using a propulsion system based on the fundamental physical principles outlined in the 17th century by Sir Isaac Newton. By the 19th century, rockets were being used in warfare, as the delivery system for exploding warheads.

The development of a rocket capable of space travel proved to be a lengthy and costly process, interrupted by frequent setbacks. The first person to propose rockets as a means of space travel was Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a Russian teacher and visionary. His groundbreaking theories on spaceflight, especially the 1903 work Investigation of Outer Space by Reaction Devices, outlined the potential advantages and disadvantages of rockets operating in space. His theories were proved by American physicist and inventor Robert Goddard who, like Tsiolkovsky, recognized that in order to reach space, a rocket must be propelled by a liquid form of fuel. In 1926, Goddard successfully launched the first liquid-fuelled rocket, an event credited as marking the beginning of the Space Age.

The U.S. government showed little interest in supporting Goddards work on rockets, but the situation was different in Germany. During the 1940s, the rocket engineer Werner von Braun led a team that developed a series of experimental rockets. The project culminated with the V-2 rocket, which was used as a weapon during World War II.

After the war ended in 1945, political tensions shifted as United States and the Soviet Union entered the Cold War. Both nations began an arms race and established massive programs to develop new weapons arsenals. Both nations recruited German rocket scientists, and within two years, they each had tested their own V-2 rockets.

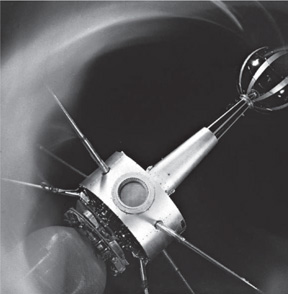

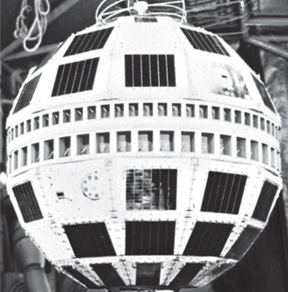

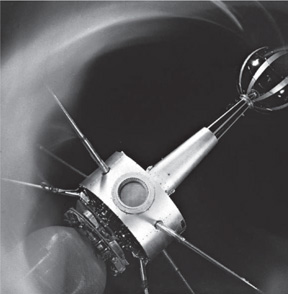

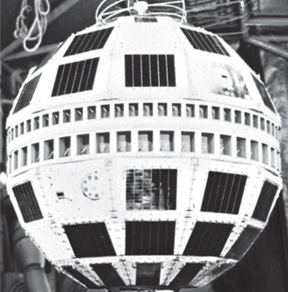

In 1957 the Soviets launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite to orbit Earth. Launched using a modified intercontinental ballistic missile, Sputnik was an 83-kilogram (184-pound) sphere that communicated information such as temperature readings to a ground station by shortwave radio. The launch became a symbol of Soviet technological progress in the Cold War. In response, the United States scrambled to accelerate its own space program. In 1958, a Jupiter-C rocket designed by von Brauns team blasted into space with the first American satellite, the Explorer 1.

Next page