Published in 2019 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2019 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2019 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Alex Ward: Editorial Director, Book Development Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor Michael Hessel-Mial: Editor Greg Tucker: Creative Director Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Earth 2.0: the search for a new home / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York : New York Times Educational Publishing, 2019. | Series: Looking forward | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642821314 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642821307 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642821321 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Extrasolar planetsJuvenile literature. | Habitable planetsJuvenile literature. | Life on other planets Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC QB820.E378 2019 | DDC 523.2'4dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

On the cover: An artist's rendering of Kepler-452b, the first nearEarth-size planet orbiting in the habitable zone of a sun-like star; NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech/T Pyle.

Contents

Introduction

when people invoke the phrase Earth 2.0, more questions are raised than answered. Will Earth 2.0 be a planet nearly identical in size to our own, orbiting a star like ours? Can it be slightly smaller, like Mars or the moon? Must it be habitable when we get there, and if not, can we find ways to create breathable air and a livable biosphere? Last and most important of all, where is it, and how will we get there? Until we find answers to these questions, Earth 2.0 is more remote than Alpha Centauri, itself 4.4 light-years or about 25 trillion miles away.

By the measure of human spaceflight, our progress appears to have stalled. When NASA astronauts first set foot on the moon in 1969, it was undoubtedly a win for the United States in the space race against the Soviet Union. But after the last visit to the moon in 1972, this ambitious period of deep space human spaceflight came to an end, as NASA directed its focus to the space shuttle program, Earth-orbiting space stations, space probes through the solar system and space telescopes. As the shuttle program came to an end in 2011 and President Obama canceled preparations for another trip to the moon, it would appear that broader interest in space has waned.

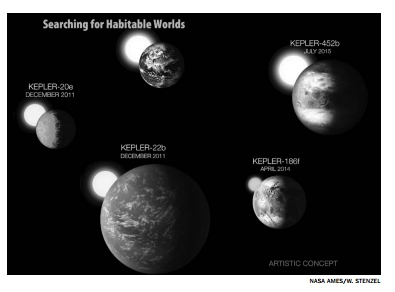

However, in the last three decades our understanding of what makes a habitable world has surged. It started when we learned how to look for them. Since the first confirmed exoplanet (planet orbiting a star that is not our own) in 1995, we have discovered nearly 4,000 planets in a variety of forms: hot Jupiters, mini-Neptunes, superEarths and the rare planet close in size to our own, an Earth analog. Scientists have used a variety of methods, including measuring minute gravitational distortions and flickers of light caused by planets orbiting their stars, and found Earthlike planets to be remarkably common.

Improvements in space telescopes have allowed for more fine-tuned searches, allowing the discovery of hundreds of planets in the habitable zone where liquid water may allow life to flourish. While we have yet found no evidence of life outside of Earth, weve learned more about how it may occur, how solar systems form and the most common types of planets.

While researchers have enjoyed a golden age of exoplanet exploration, developments on Earth and in our solar system have been significant. While NASA remains the largest space agency in the world, leading in technological development, it has seen competition from emerging powers and for-profit space enterprise. Emerging powers such as China and India have developed their space programs to build national prestige. Meanwhile, companies SpaceX and Blue Origin, founded by Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos respectively, have shifted space enterprise from the earlier space tourism model to developing technology and services for public space agencies. While these changes are rooted in national competition and the search for profits, space research remains a work of international cooperation, sharing information and expertise. This work has led to the European Space Agency landing a probe on a comet, the burgeoning Indian Space Research Organization successfully launching a Mars probe on its first attempt, and the discovery of methane on one of Saturns moons, Enceladus a possible sign of life.

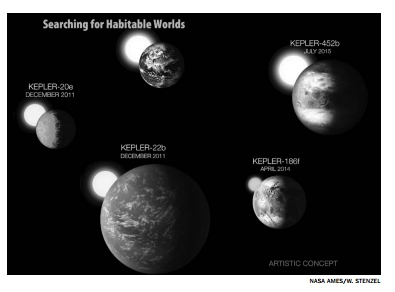

An artists rendering that shows the sweep of the NASA Kepler missions search for planets within the habitable zone.

As diverse fields of space research expand and converge, one planet maintains its hold on the public imagination: Mars. The so-called Red Planets habitability has been a source of speculation for centuries, and many dream of one day living there. On both of those fronts, we have moved closer. SpaceX founder Elon Musk asserts that the longterm plans for his rocket technology involve sending space colonists to Mars, while researchers examine how the planets iron-rich soil might accommodate agriculture. More concretely, the newest generation of Mars rovers have discovered evidence of flowing liquid water, which may host microbial life. If life exists on Mars, the next decades explorations may have the tools to discover it.

The search for Earth 2.0, like other space research, invites skepticism. Why waste resources to find a habitable planet trillions of miles away when there are so many pressing issues on our own planet? Some of those views also appear in this book, as a part of the broader conversation about what Earth 2.0 means in the context of a warming planet and growing social inequality. As other reflections in this book demonstrate, the exploration of our universe by telescope, by space probe and by terrestrial laboratory research helps us better understand our own planet and the life it fosters.

Chapter 1

A Golden Age of Exoplanet Research

In 1995, exoplanet 51 Pegasi b was discovered the first confirmed planet orbiting a star like our own. By the middle 2010s, space telescopes like Kepler had discovered thousands of widely varying exoplanets: hot Jupiters, super-Earths, mini-Neptunes and others that revealed new rules for the formation of solar systems. With them, the occasional habitable Earth-sized planet raised questions: Does life exist there? Could humans visit? While both questions remain unanswered, these discoveries raised the profile of space research.

In a Golden Age of Discovery, Faraway Worlds Beckon

BY JOHN NOBLE WILFORD | FEB. , 1997

standing outside the dome of Lick Observatory on this lofty summit, two astronomers gazed beyond the foothills to the far horizon where California meets the Pacific Ocean. As the solid world at their feet rotated east, the great red sphere of glowing hydrogen seemed to sink perilously close to a doomsday collision, only to slip harmlessly out of sight in the west.