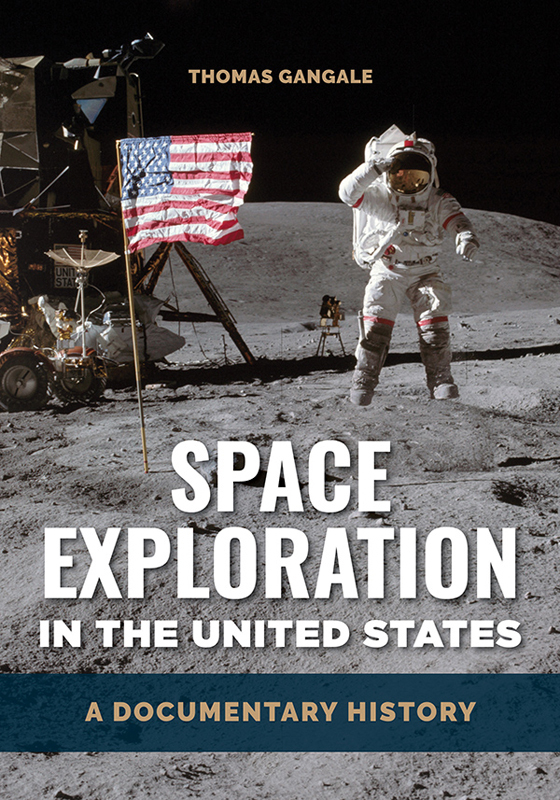

Space Exploration in the

United States

Space Exploration

in the United States

A Documentary History

THOMAS GANGALE

Copyright 2020 by ABC-CLIO, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gangale, Thomas, editor.

Title: Space exploration in the United States : a documentary history / [edited by] Thomas Gangale.

Description: Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019020193 (print) | LCCN 2019021916 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440871658 (eBook) | ISBN 9781440871641 (hardcopy : acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: AstronauticsUnited StatesHistorySources. | AstronauticsGovernment policyUnited StatesHistorySources. | Outer spaceExplorationUnited StatesHistorySources. | Speeches, addresses, etc., American.

Classification: LCC TL789.8.U5 (ebook) | LCC TL789.8.U5 G36 2020 (print) | DDC 629.40973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019020193

ISBN: 978-1-4408-7164-1 (print)

978-1-4408-7165-8 (ebook)

24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available as an eBook.

ABC-CLIO

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

147 Castilian Drive

Santa Barbara, California 93117

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

This collection of historical documents provides insight into the history of the United States in its pursuit of the peaceful uses of outer space, with emphasis on the manned space program of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration as well as on commercial American activities supporting human spaceflight in the early 21st century. Of course, the early history cannot be entirely understood without some reference to German rocketry in the 1930s and 1940s and Soviet space efforts in the 1950s through the 1980s, just as the later history cannot be entirely understood without some reference to Russian space activities since the 1990s. Also important to the understanding of this collection of historical documents is knowledge of the domestic American politics that influenced the course of Americas space program. The introductions to the individual chapters seek to provide some of this context.

The reader will note that the author uses the adjectives manned, piloted, crewed, and human interchangeably in the chapter introductions. In the early decades of the space age, the term manned was used exclusively, as reflected in the documents of those years; thus, the author uses that adjective more when discussing this period, while the gender-neutral adjectives are more often used for the later years, as language has changed.

Rocketry and space technology have served several goals throughout the Space Age: pure research, as well as applied research for national security, national prestige, and commercial profit. There have been various agents of this research as well: individuals supported by philanthropists as well as governments, intergovernmental organizations, international consortiums, and for-profit corporations. So, when the question is asked, Why go into space? there are many answers: to make money for our investors, to promote the general welfare, to provide for the common defense, or to explore strange new worlds.

However, the present volume focuses on space exploration, and in particular, human space exploration, so the question to consider is Why should humans go into outer space? It is difficult to summon a pragmatic argument, and it is for this reason that military manned space projects have come to very little; putting man in the loop did not appear to be worth the expense. On the other hand, the science journalist Jules Bergman pointed to the repairs to the Skylab space station in 1973 as proving the utility of humans in space. Similarly, correcting the Hubble Space Telescopes mis-figured optics was beyond the ability of machines of the 1990s; it took humans to accomplish that and save the HST from being a billion-dollar debacle. During the first decade of spaceflight, automated systems were crude and unreliable, and whereas humans required additional systems for their survival in the lethal environment of space, they could be readily trained to perform a variety of missions, and they possessed the flexibility to adapt to unexpected challenges, which automated systems lacked. For instance, in the 1960s and 1970s, 2 of the 7 U.S. attempts to land automated spacecraft on the Moon failed, and 7 of the 15 Soviet automated spacecraft that attempted landings on the Moon crashed. In contrast, all 6 Apollo missions, which attempted lunar landings, succeeded. Their pilots could observe and judge the treacherous terrain in real time and make the necessary adjustments to save the missions from disaster. In particular, an automated landing at the Apollo 11 site, which was chosen for its supposed safety, surely would have crashed in a boulder field.

In contrast, the two Chinese attempts to land on the Moon in the 2010s have succeeded; a perfect record so far. Robotic systems have become more reliable. The record of attempts to land automated probes on Mars in the course of the past half century supports this. In the 1970s, only two of six attempts succeeded; in the 1990s, one out of two, but in the 21st century, five of seven landing attempts have succeeded. Advances in robotics later in our century may enable machines to perform all the useful activities that humans now perform in space; if so, the question of why humans should be out there at all may become ever more difficult to answer in the positive.

If there is little practical purpose for humans venturing into space, what is left other than that which makes us most human, which distinguishes us both from other life-forms and from machines: the sense of wonder, the desire not only to acquire new knowledge but to experience new realms; perchance to dream, perhaps to touch the face of God. Is it possible that this is the practical purpose for humans going out there?

To set foot on the soil of the asteroids, to lift by hand a rock from the Moon, as the Russian mathematician Konstantin Tsiolkovsky described it more than a century ago, is only the beginning of the human experience. Stepping out of that cradle of the mind that he called Earth has afforded a new perspective, one that has been called the Overview Effect, the overwhelming sense of human unity, and indeed, the planetary unity of all of Earths life-forms, which one experiences when looking down at a world without borders from hundreds of miles above. For the dozen men who walked on the surface of the Moon, Earth was a small blue marble in the black sky, blotted out by simply holding up ones thumb, so alone, so precious, so fragile, containing all of us in our billions. The poet Archibald MacLeish wrote during the Apollo 8 mission, which orbited the Moon on Christmas Eve 1968, that we are riders on the Earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal coldbrothers who know now they are truly brothers.