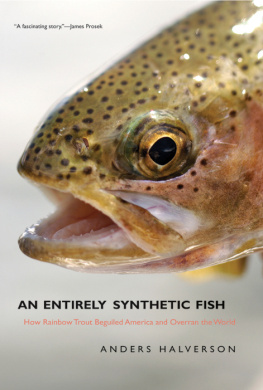

An Entirely Synthetic Fish

An

Entirely

Synthetic

Fish

How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America and Overran the World

Anders Halverson

Yale University Press

New Haven and London

Published with assistance from the Louis Stern

Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2010 by M. Anders Halverson.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part,

including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying

permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright

Law and except by reviewers for the public press),

without written permission from the publishers.

Designed by Sonia Shannon

Set in Palatino type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.,

Durham, North Carolina.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Halverson, Anders, 1969

An entirely synthetic fish : how rainbow trout beguiled

America and overran the world / Anders Halverson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-14087-3 (alk. paper)

1. Rainbow trout. 2. Introduced fishesUnited States.

3. Rainbow trout industryUnited StatesHistory.

I. Title.

QL638.S2H187 2010

639.3757dc22

2009036200

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO

Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Ginna

Contents

Foreword

PATRICIA NELSON LIMERICK

Complaints are everywhere heard that the public good is disregarded in the conflict of rival parties, founding father James Madison wrote in a passage that sounds as if he planned a second career as an environmental policy analyst. When Madison expressed this thought in The Federalist Papers, however, he did not have recreational fishermen, advocates of biodiversity, state and federal resource managers, or business owners in resort communities to cite as his examples. But if we could summon Madison for a twenty-first-century site visit to any popular trout-fishing stream, he would arrive with a well-designed conceptual framework ready to apply. As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, Madison wrote, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his self-love, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other. And with reason and self-interest thus entangled, Madison concluded, the latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man.

The qualities of human nature that worried Madison have come to thrive in environmental disputes today. And yet, facing off against the generous and open spirit of Anders Halversons An Entirely Synthetic Fish, faction and its comrade-in-arms, unreasoned passion, back down and come close to apologizing for all the trouble they have caused. Tracing the massive enterprise that produced rainbow trout in hatcheries and dispersed them worldwide, Halverson explores a case study full of implication for hundreds of other environmental matters. In truth, his approach sets a model for taking on topics of contention and conflict. This book combines a respectful and empathetic exploration of the beliefs and attitudes that guided this extraordinary project in the rearrangement of nature with a well-informed and clear presentation of scientific findings on the projects consequences.

With that combination, this book rewards readers in two equally significant ways. First, it entertains us with stories of intrinsic interest and even mind-stretching improbability. Second, it invites us to be smarter and more congenial citizens, more inclined to think productively about our environmental challenges and dilemmas, and more prepared to rise above faction and return to regarding the public good.

The stories are indeed extraordinary. Post-Civil War transporters of fish eggs endured exhausting railroad trips, denied sleep for a week as they added ice and water to keep the eggs alive. After World War II, the California Department of Fish and Game took the practice of fish transportation in an even more improbable direction, populating the once fish-free lakes of the Sierra Nevada by acquiring surplus military planes and launching cascades of fish in free fall into the water. Then, after years of purposeful stocking of hatchery fish, alarm over the threat posed to endangered native fish led, in many locations, to an about-face, with fish eradication projects diametrically reversing the meanings of success and progress. And, in the most intriguing plot twist of all, the fish have taken over the action, as native fish and introduced fish get down to business and produce a new kind of fish: hybrids whose muddled DNA challenges laws and policies designed to deal with a considerably more predictable and tractable material world. Never a simple matter, the goal of preserving an endangered species becomes dramatically more complicated when the species itself does not hold still and retain a steady identity.

And, at this point, Halversons stories begin their own move toward hybridity, emerging as factually accurate recountings that also present the DNA markers of parables and fables. While readers who simply want to savor and enjoy the ride will have a fine time, the stories are ready to deliver a much greater and more consequential reward. People can treat this book as exercise equipment for the intellect and imagination, a device to strengthen and stretch the minds powers to reflect and to analyze in the most useful way.

Heres an example of the usefulness I have in mind.

In the early 1990s, I spoke at the annual conference of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies and met a memorable group of professionals. In truth, with his very biodiverse ark, Noah could be cast as the father and founder of this particular profession. The audience was made up of state officials charged with managing a vast range of diverse creatures: furred and scaly, colorful and dull, charismatic and unnerving, endangered and abundant, game and non-game. In the late afternoons, a good-hearted person, who himself seemed to be a hybrid of sociologist and therapist, conducted sessions to help these managers reduce the stress and tension of dealing with the most vexing and trying organisms of all: the human constituents (a.k.a. factions) whose dreams, desires, and demands made the professional lives of the managers so challenging.

At the beginning of one session, our sociologist-therapist-hybrid leader instructed us to draw pictures of vicious circles that characterized our professional lives. Professors are not bereft of material for such an assignment, and I sketched my own poignant diagram of one recent loop of escalating university miscommunication. But then, as we settled in to contemplate one anothers diagrams, my companions troubles trumped and dwarfed my own. Their vicious circles all followed a path of initial constituent demands, to which the managers responded as helpfully as they could. From there, the circles diverged between successful responses to demands that then led the constituents to believe that they could get what they wanted (usually a robust population of game fish, deer, or wildfowl) and thus led them to demand even more, or, unsuccessful responses that threw the dissatisfied constituents into a frenzy of escalating demands. Either way, with each turn of the circle, the professional lives of the wildlife managers ratcheted up another notch or two in tension and vexation. And, as the managers tried to respond to the demands of one particular faction, the demands of many other factions came at them at an unrelenting pace, as, for instance, environmental groups questioned the whole project of letting the preferences of hunting and fishing advocates set the priorities of wildlife management.

Next page