Also by WAYNE FANEBUST

Brigadier General Robert L. McCook and Colonel Daniel McCook, Jr.: A Union Army Dual Biography (McFarland, 2017)

Major General Alexander M. McCook, USA: A Civil War Biography (McFarland, 2013)

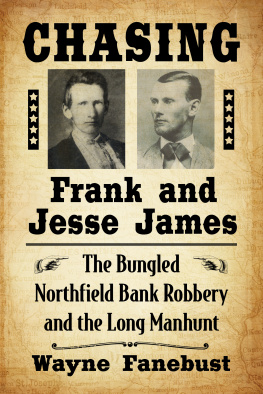

Chasing Frank and Jesse James

The Bungled Northfield Bank Robbery and the Long Manhunt

WAYNE FANEBUST

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3189-9

2018 Wayne Fanebust. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover images of Frank James (Clay County, Missouri, Photograph Collection [P1112]. 023962. State Historical Society of Missouri, Photograph Collection) and Jesse James, ca. May 22, 1882 (Library of Congress)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Preface and Acknowledgments

From 1865, the year the Civil War ended, to the 1880s when the last of the JamesYounger gang had been killed, imprisoned, or had simply disappeared, there was a tension among the people of Missouri between the need for law and order and the desire to protect certain outlaws, their comrades, the last Rebels. The James brothers and their cohorts were the products of the Confederacy and the war it fought against the Union in defense of secession and slavery. The defeat of the Southern army created lasting bitterness in the South and a burning desire to right the wrong, so to speak.

At the same time the James gang was robbing banks, stagecoaches and trains, others were busy re-writing history, creating the myth of the Lost Cause, a false picture of the Confederacy and the Civil War. The never-say-die outlaws played into that narrative by refusing to lay down their guns and put their shoulders to the plow. Instead they attacked Yankee banks and committed other acts of violence to remind the less daring Southerners that the war was not really over.

The bandits were sticking it to the authorities in a manner that some men admired but could not bring themselves to act out. So they watched the violence from the sidelines, secretly or openly supporting the criminal acts of the James gang, including the Younger brothersall heroes in the minds of the grim and melancholy Southern patriots, the believers in wholesale redemption. The lack of effort from law enforcement was a re-enforcement of the public apathy or sympathy for the outlaw. It was plain to the casual observer that little or nothing was being done to capture or kill the outlaws. And when they were not out freebooting, robbing, and killing, the outlaws moved freely and openly from place to place almost as if flaunting their lawlessness, seemingly daring someone to make a move against them.

When the Civil War ended, the James brothers and Cole Younger, all former guerrillas under the vicious William Clark Quantrill and William Bloody Bill Anderson, were denied amnesty, but it is not certain that they would have accepted it had it been offered. Instead they turned to a life of crime, using the refusal of amnesty as an excuse. From 1866 to 1876, they were successful in robbing, killing and spreading terror and escaping punishment. From the Missouri governor on down, there was very little enthusiasm for rounding up the criminals and putting an end to the robbery and murder. The state government at Jefferson City was seemingly out to lunch, with a blind eye toward the crime and carnage, and the cost in lives and money.

But while Missouri, sneeringly dubbed the Robber State or the Bandit State, was at best ambivalent in its attitude toward putting a stop to the crime epidemic, the northern states were firm in their denunciation of outlawism, and they offered no sympathy, nor did they look upon the banditti as bold, daring heroes. To people outside of the South, the James brothers and their associates were bad people, criminals who committed terrible crimes, men who deserved hanging. They were recognized as being very good at their line of work, but not invincible.

So it was a huge mistake for the JamesYounger gang to venture forth into Minnesota, looking for fat bank to rob. It was extremely arrogant of the Missouri outlaws to think that the hard-working farm and business people of the northern prairie would simply run away once the shooting started. And when the shooting started at Northfield, Minnesota, the townspeople offered stiff and brave resistance, exchanging gunfire with gunfire. When the shooting stopped, two outlaws lay dead in the street, and the rest were shot up and sent riding for their lives. Two citizens of Northfield were killed in shocking crime that set in motion, one of the greatest and most exciting manhunts in American history.

This book is about that manhunt, that great escape by Frank and Jesse James through southwestern Minnesota, southeastern Dakota Territory, and thence into Iowa and finally back home in Missouri. The bank robbery itself and capture of the Younger brothers will also be explained in some detail, but the meat of the book will be an account of the mile by mile, day by day escape by the James brothers, both of whom were wounded and in need of medical care. That they were able to keep out the grasp of the numerous bands of man hunters, find food at homesteads, get directions from kind but unknowing settlers, cross rivers and creeks and steal horses when needed, until at long last, they reached Clay County, Missouri, their home base, has to rate as one of the most unlikely and sensational accomplishments in the history of the American West.

But it is a subject the James brothers never talked about, or if they did, the discussion never found its way into print. And yet the Northfield raid and the great escape combined to form the vehicle that sent the James brothers speeding into history, riding an express train of unparalleled popularity and notoriety. Books, stage presentations, Wild West shows, re-enactments, and finally movies and television, all tell their story with varying degrees of accuracy and truth. But it matters not, for Frank and Jesse James are Americas most famous outlaws. They earned the award the hard way, and in the American mind, they have a strong and lasting grip on the trophy.

One day while talking to some friends about my writing projects, I mentioned that I was working on a book about Frank and Jesse James. Not surprisingly, I was questioned about the subject: What could I possibly write about them that was not already in print? Good question, of course, but I replied that the great escape from Northfield was the one part of their lives that others have ignored or glossed over, and yet, to my thinking, it was the greatest and most singular achievement of their outlaw careers. So I forged ahead with the project and I now lay it before the reading public, armed with the thought that there is room on the bookshelves of America for one more book about the James brothers.

The research and writing of this book was a mission of pleasure, made relatively easy by the newspaper archives in the Library of Congress. The digitizing of millions of newspaper pages, and the ease with which one can access the site called Chronicling America, has brought to light a vast number of newspapers that had seemingly disappeared from memory long ago. Having the resource available allowed me to find useful and relevant information that has never before appeared in print.

Next page