Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2012 by James W. Erwin

All rights reserved

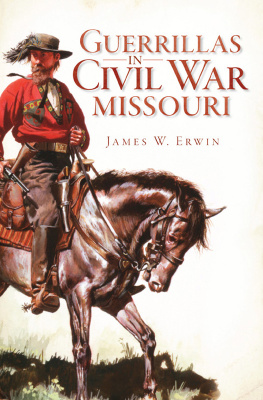

Front cover: Quantrills Guerrillas, Missouri Partizan Rangers, 1863, by Don Troiani.

www.historicalimagebank.com.

First published 2012; e-book edition 2012

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.61423.362.6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Erwin, James W.

Guerrillas in Civil War Missouri / James W. Erwin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-388-2

1. Missouri--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Underground movements. 2. Missouri--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Commando operations. 3. Missouri--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Campaigns. 4. Guerrilla warfare--Missouri--History--19th century. 5. Guerrillas--Missouri--History--19th century. I. Title.

E470.45.E78 2012

977.803--dc23

2011050227

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Preface

During the Civil War, Missouri was in constant turmoil from raids by heavily armed bands of marauders loosely affiliated with the Confederate army. Federal troops fought more than one thousand battles in Missourimostly with these guerrillas. But the numbers mask the level of violence because they do not include attacks on civilians. Ordinary persons felt the dread of uncertainty when riders approached their homes. Were they Union soldiers or guerrillas in blue coats taken off soldiers they had ambushed? Sometimes it did not matter. Either side might kill the men and burn their buildings if dissatisfied with the response to their demands for information, food or horses. Entire counties were reduced to ruins.

A Civil War clich is that the war pitted brother against brother. No doubt that must have happened, but Missouris civil war was personal on another level. As General John Pope wrote, it was a frequent occurrence for a party of bushwhackerswith fierce oaths and loud threats of burning his house to demand that a man or (more likely during the war) his wife provide food, horses and money. The guerrillas and their victims were not strangers. They were neighbors from the family down the road. And the guerrillas families could expect the same treatment from other neighbors who were members of the Missouri militia or, worse, Jayhawkers from Kansas.

There were few set-piece battles in Missouri. It was left to the armies in the other theaters to provide the dramatic charges and heroic defenses. In Missouri, a soldier may be shot riding down a seemingly peaceful road. A guerrilla unlucky enough to be captured would somehow always be reported as shot trying to escape.

After the war, the former antagonists debated who was responsible for the escalating cycle of killing, retribution and revenge that became ever more savage as the war continued. Who was the first to scalp the dead enemy? Who was the first to mutilate the bodies of the dead? Once it began, however, the origins no longer mattered. Postwar author John N. Edwards wrote of Jesse Jamesbut it could have been applied to any man caught up in the guerrilla warHe did what he did. But it was war.

This was Missouris guerrilla war: a war of retaliation, savagery and few prisoners.

Acknowledgements

My debt to the historians listed in the bibliography is evident. I hope that this introduction to the guerrilla war in Missouri will make the reader want to learn more about the subjects these authors have explored in depth.

I want to acknowledge the assistance of Sara Przybylski at the State Historical Society of Missouri at Columbia, Missouri, and Dorris Keeven-Franke at the St. Charles Historical Society for their help in obtaining photographs and illustrations for this book. I also want to thank Colter Sikora for the excellent maps.

Finally, I must give the most credit to my wife, Vicki. Without her encouragement, suggestions and, yes, prodding, this book would never have been conceived, let alone completed. Thanks, Vicki, I love you.

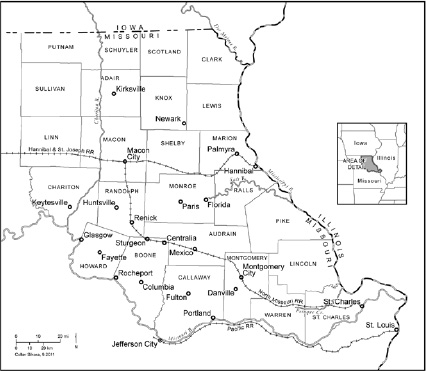

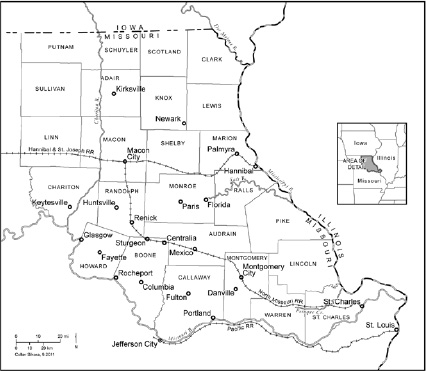

North central and northeastern Missouri. Little Dixie extended from Callaway County on both sides of the Missouri River to Jackson County. Map by Colter Sikora.

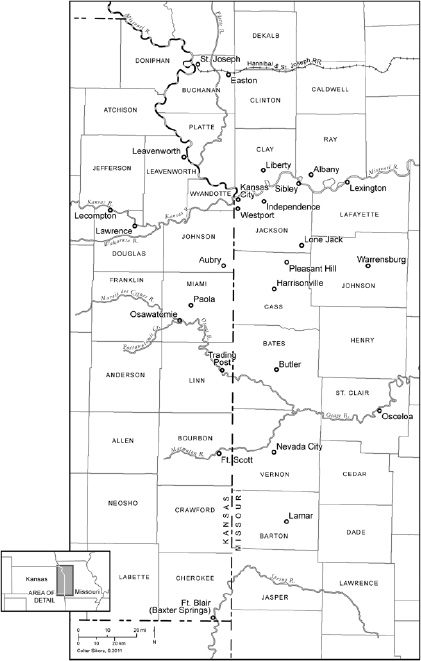

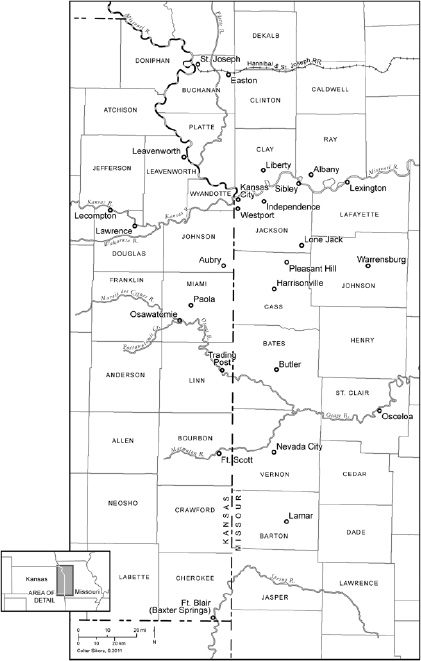

Western Missouri and eastern Kansas. The area affected by Order No. 11 was Jackson, Cass, Bates and the northern third of Vernon Counties. Most of Missouris slaves lived in Little Dixie, the counties along the Missouri River. Map by Colter Sikora.

Chapter 1

The War Before the War

THE KANSAS-NEBRASKA ACT

The roots of the guerrilla war in Missourilike the Civil War itselfcan be traced to the issue of slavery in the territories.

Missouri was part of the Louisiana Purchase. While the states application to become a state was pending, Alabama was admitted as a slave state, making the number of slave and free states equal. The impasse was broken by an agreement to admit Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. The Missouri Compromise settled the question of allowing slavery in states created from the Louisiana Territory, at least for the time being, by prohibiting it north of the 3630' parallel, the southern boundary of Missouri.

Few were satisfied, but the arrangement maintained sectional balance and kept the question of slavery in newly acquired lands from further dividing the country. Thomas Jefferson rightly considered that the slavery issue was hushed indeed for the moment, but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. [A] geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.

And indeed, the question of the extension of slavery erupted after the United States again acquired considerable territory, this time as a result of the Mexican War. The dispute raged for four years until Congress approved the Compromise of 1850. Under this agreement, Texas was admitted to the Union, all of California (even the part south of the 3630' parallel) was admitted as a free state, a stronger Fugitive Slave Act was passed and slavery was preserved in the District of Columbia. But the Compromise of 1850 was doomed to last only four years.

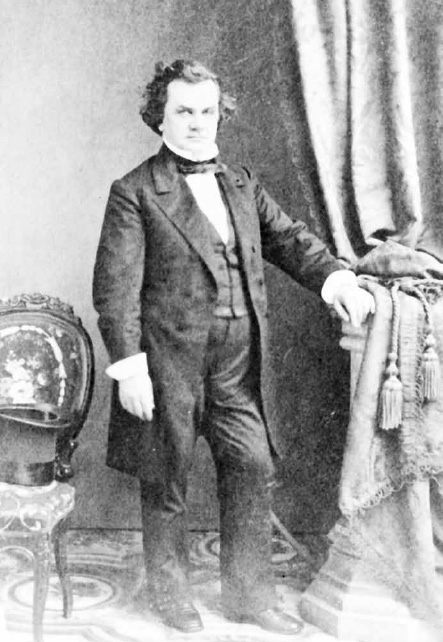

Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas, author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 and Democratic candidate for president in 1860. Library of Congress.

Senator Stephen A. Douglas thought he had the solution to the political turmoil that had racked the country for decades over slavery and threatened to divide his Democratic Party: popular sovereignty. Let the people decide. In January 1854, he introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which proclaimed that the questions pertaining to slavery in the territories, and in the new states to be formed therefrom, are to be left to the decision of the people residing therein, through their representatives.

Next page