Copyright

Copyright 2016

By Larry Wood

All rights reserved

The word Pelican and the depiction of a pelican are

trademarks of Pelican Publishing Company, Inc., and are

registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

ISBN: 9781455621569

E-book ISBN: 9781455621576

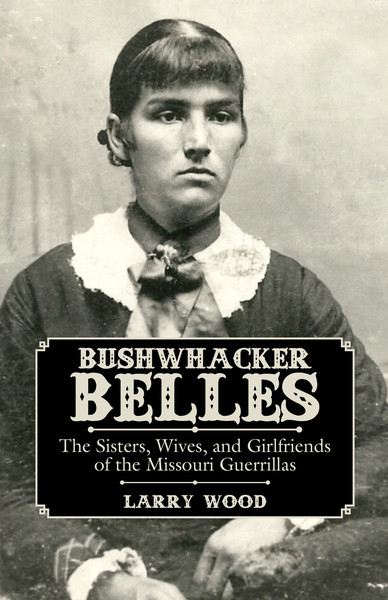

Eliza Gabbert photo courtesy of Bushwhacker Museum.

Printed in the United States of America

Published by Pelican Publishing Company, Inc.

1000 Burmaster Street, Gretna, Louisiana 70053

War has historically been considered the purview of men, but women have played significant roles in many of Americas conflicts. This, of course, has been particularly true of recent wars, as females increasingly perform combat functions previously reserved for males. However, even during the Civil War over a century and a half ago, women played crucial parts. Occasionally they disguised themselves as men, donned uniforms, and fought alongside men. More often, they supported the war effort by performing auxiliary functions. Some served in official capacities as nurses, cooks, and washer-women, while others acted covertly as spies and messengers.

For the first one hundred years or more after the Civil War, little attention was paid to the role that women played in the conflict. Scholarship over the past half-century has largely filled the void. Mary Elizabeth Masseys 1966 work, Bonnet Brigades (later republished as Women in the Civil War ), was one of the first serious studies of women in the Civil War. Massey found that most women participated in the war unintentionally, and hers was a study of how the war affected women, not how women affected the war.

Subsequent work, on the other hand, tends to focus on the role the Civil War played in empowering women, examining the endeavors women undertook during the war as avenues of liberation. For example, Victoria E. Bynums 1992 book, Unruly Women: The Politics of Social and Sexual Control in the Old South , explored how the disorderly behavior of poor, powerless women in North Carolina during the Civil War gave them a voice in the public arena and threatened to disrupt the male-dominated social order. Laura F. Edwards Scarlett Doesnt Live Here Anymore , published in 2000, showed that the struggles of poor, Southern women during the Civil War era had political implications, even though the women were not consciously striving for power or independence. In 2002, DeAnne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook, in They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War , provided a wide-ranging and fascinating look at women who donned uniforms or otherwise disguised themselves as men and fought as soldiers. Published in 2010, Stephanie McCurrys Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South built on the work of Bynum and others to show that, although women were considered outside politics and war, the Civil War forced both Confederate and Union authorities to deal with them.

Perhaps no other state saw a greater proportion of its women involved in the Civil War, especially in covert roles, than the slave-holding border state of Missouri. Although Missouri stayed in the Union, the sentiments of its citizens were sharply divided. The state was soon drawn into a bitter guerrilla conflict marked by sabotage, raids, and personal vendettas. The war in their own back yard drew the states civilians, including women, into the conflict. Neighbor was often pitted against neighbor. Southern-sympathizing women with guerrilla family members or close friends often fed and sheltered the partisan fighters in their homes.

Other Southern women in Missouri took an even more active role in helping the Rebel cause by spying and carrying information to bushwhackers or to Confederate soldiers. Because of the virulent and personal nature of the guerrilla warfare, more women in Missouri clashed with Union authorities during the Civil War than in almost any other state. Many were arrested, some accused of what the Union considered serious offenses and tried by military commission.

Countless books and articles have been written about the guerrilla warfare in Missouri, chronicling the lives and military careers of many of the individual guerrillas. In fact, some of their stories, such as that of William Quantrill, have been told repeatedly. Yet historians and writers have paid little notice to the role played by family members of the guerrillas, particularly their female loved ones. A few generally unreliable accounts of some of the supposed exploits of the female abettors of Missouri guerrillas were published during the late nineteenth century. These paint the women as either romantic heroines or depraved she-devils, depending on which side the author identified with. During the early twentieth century, a few old women who had been associated with the guerrillas as girls wrote reminiscent accounts that perpetuated the idea, first promulgated during the war, that women had little role in the conflict except as victims of a cruel Union Army.

Michael Fellmans 1989 work, Inside War : The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War , was one of the first scholarly works to look beyond the military narrative and examine the social and psychological impact of the guerrilla warfare in Missouri. It contained a chapter dealing specifically with women. While allowing that women sometimes willingly participated in Missouris guerrilla conflict, Fellman overall accepted the portrayal of the females as victims of barbarous warfare in the state. Most subsequent scholars explore the part played by women in the guerrilla conflict in Missouri only incidentally within the larger context of examining the role and influence of women in the Civil War in general.

Only a few authors besides Fellman have looked at Missouri women during the war. Joseph Beilein, Jr., in his 2006 masters thesis, The Presence of These Families Is the Cause of the Presence There of the Guerrillas: The Influence of Little Dixie Households on the Civil War in Missouri , examined a few female-headed households along the Missouri River that served as places of refuge and support for guerrillas. Countering the idea that Missouri women during the Civil War were primarily victims, Beilein expanded on Bynums concept of unruly or disorderly women to argue instead that the women acted with agency and freewill to affect the outcome of the war. However, Beileins study was limited to a handful of subjects. In 2006, Confederate Heroines by Thomas Lowry profiled 120 Southern women, including a number of Missouri women, tried by Union military proceedings during the Civil War. However, Lowry presented some of the stories as illustrative sketches rather than thorough accounts; several of the remarkable cases he chronicled involved women who were not arrested for aiding guerrillas but rather for offenses such as smuggling mail into St. Louis prisons. In addition, many interesting cases of women arrested for aiding guerrillas never came to trial and were therefore not included in Lowrys study.