Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2013 by James W. Erwin

All rights reserved

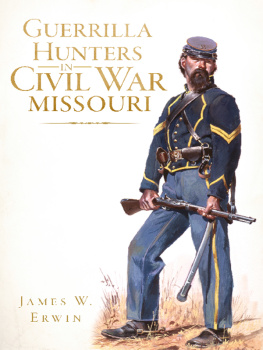

Cover image: painting by Don Troiani, www.historicalimagebank.com.

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.61423.899.7

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.60949.745.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Ben Gibson and everyone at The History Press for the opportunity to realize a dream I have had since I was eight years old: to write about the Civil War. In the preparation of this book, I have received valuable assistance from, in no particular order: Dorris Keeven-Franke at the St. Charles County Historical Society; Sean Visintainer, curator, Herman T. Pott National Inland Waterways Library at the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of MissouriSt. Louis; and Deborah Wood, museum curator, Wilsons Creek National Battlefield. I owe a debt to Veronasorry I did not get your last namewho told me of a story that, serendipitously, was confirmed by documents from Margie Heppermann Summers. Peter Cauchon provided valuable books and encouragement. And I cannot thank my mapmaker, Colter Sikura, enough for producing maps on a short deadline.

I also wish to acknowledge my parents, Juanita and Charles Erwin. My profound regret is that they did not live to see the book published. Mom instilled a love of reading and research. Dad patiently drove a kid all over southwest Missouri and northwest Arkansas looking for battlefields years before they were marked, armed only with a musty history book and a state highway map.

Finally, my wife, Vickiby the example of writing her own booksshowed me the dedication and hard work necessary to bring this work to fruition. I owe her so much more than I can put into words.

Prologue

Amanda Sawyer was almost home. She boarded the Hannibal & St. Joseph train early that morning in Palmyra, Missouri, on the other side of the state. It was now almost 11:00 p.m., and the train had left Easton, just a few miles from St. Joseph. She would be home in Kansas tomorrow. It would be good to be home, as well as to get back to teaching.

Also on the train were Barclay Coppoc and Sidney Clarke. Coppoc, a lieutenant in the Kansas infantry, had been a member of John Browns band that attacked Harpers Ferry in 1859. He had been left at the base to guard the groups supplies and escaped the post-attack pursuit. Clarke was a personal secretary to Kansas senator (now General) James H. Lane, a prominent antislavery politician and a leader of the Jayhawkers in prewar Kansas.

The Hannibal & St. Josephs service had been intermittent at best over the last few months. Armed men had taken shots at passing trains, and service to St. Joseph was suspended altogether the weekend before this trip because it was unclear who exactly, Unionists or Secessionists, controlled the city. But federal troops there had been ordered to Lexington to oppose General Sterling Price, and on August 30, Secessionists rushed in to occupy St. Joseph. That very evening, their commanders were being fted at the Patee Hotel.

What Sawyer, Coppoc, Clarke and the others on the train did not know was that a group of a dozen armed men had been scouting the railroad for days, and on this day, September 3, 1861, the men decided to strike.

First, the guerrillas chased away the railroads section hands, who were supposed to keep watch over the bridge and track to make sure that it was in good repair. They also threatened the local residents, who might have given the alarm that something was afoot. Then the guerrillas set fire to the supports of the bridge. It weakened them to the point that the bridge would collapse, but the engineer could not see thatespecially at nightuntil it was too late.

The locomotive got about halfway across the 160-foot bridge before the supports gave way, and it crashed into the Platte River thirty-five feet below. The freight, mail and baggage cars plunged down, and the two passenger cars followed, piling one on top of the other. Quicker than I thought, Clarke recalled, I found myself buried beneath a mass of ruins. The passengers were thrown into a heap at the front of the cars, some crushed by the bridges timbers, others cut by jagged glass and others still trapped in the debris. Amid the shrieks of pain and screams of terror, Abe Hager, a baggage man, one of the few uninjured, tried to pull those who were still alive onto the banks of the river. After rescuing as many as he could from the bloody scene, Hager made his way to St. Joseph to summon assistance. According to witnesses, three or four armed men watched silently from above on the western abutment but offered no help.

Fifteen passengers, including Coppoc, and five trainmen were killed. Sawyer and Clarke survived, among the dozens who were injured.

Up to this point, the bridge burning and a few shots fired into trains constituted a relatively low level of violence. The attacks could be justified as being against military targets. The Union commanders were concerned with them, but the public was more focused on the activities of the conventional armies at Wilsons Creek (and at Bull Run in the East). But this tragedy on the Platte River was the first to involve a large loss of civilian lives. It dispelled any notion that civilians could remain neutral in the war or that guerrillas could be defeated by moral suasion or threats to confiscate noncombatants property.

To combat this threat, Governor Hamilton Gamble needed reliable troops who were capable of hunting down the guerrillas. He found them in men like George Wolz, Aaron Caton, John Durnell, Thomas Holston and Ludwick St. John. You have likely never heard of them. They are not listed among the heroes of the Civil War. They did not lead any famous charges or win any medals. They did not get to march in the Grand Army of the Republic parade in Washington, D.C., after the defeat of the Confederacy.

These men served as privates in a cavalry regiment. They spent most of their time in camp and on scouts looking for guerrillas. It was a hard life, and over three years of the war, these boys (for most were in their teens and early twenties) became hard men. Combat, when it came, was often short, sharp, brutal and unforgiving. In Missouri, neither side showed much mercy for defeated foes.

The guerrillas who terrorized Missouri during the Civil War were colorful men dressed in gaudy guerrilla shirts and plumed hats. Their daring and vicious deeds brought them a celebrity never enjoyed by the Federal soldiers who hunted them. Many books have been written about the exploits of William Quantrill, Bloody Bill Anderson, George Todd, Tom Livingston and other noted guerrillas. But in the end, men like Wolz, Caton, Durnell, Holston and St. John killed Anderson, Todd and Livingston and defeated the rest. They were just five of the anonymous thousands of Union soldiers who fought in the guerrilla war, whose participation has largely been forgotten with the passage of time. This is their story.

Chapter 1

The Wolf by the Ears

Next page