Shades of Blue and Gray Series

Edited by Herman Hattaway, Jon L. Wakelyn, and Clayton E. Jewett

The Shades of Blue and Gray Series offers Civil War studies for the modern readerCivil War buff and scholar alike. Military history today addresses the relationship between society and warfare. Thus biographies and thematic studies that deal with civilians, soldiers, and political leaders are increasingly important to a larger public. This series includes books that will appeal to Civil War Roundtable groups, individuals, libraries, and academics with a special interest in this era of American history.

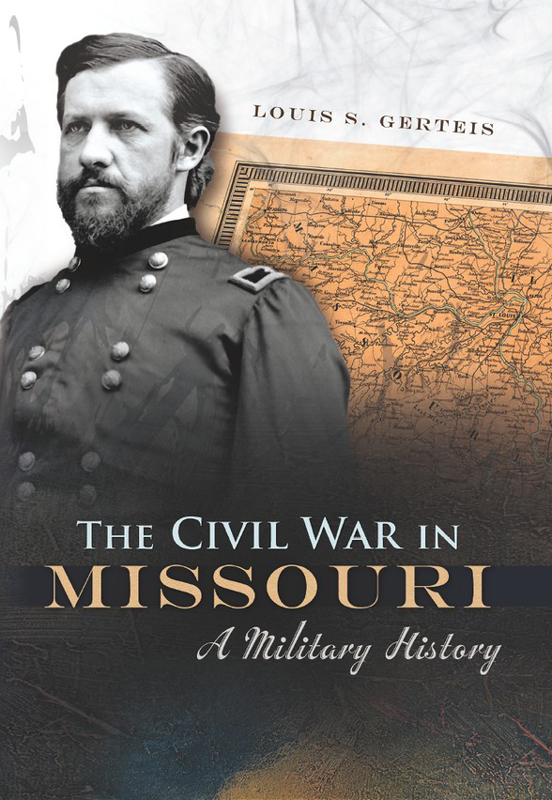

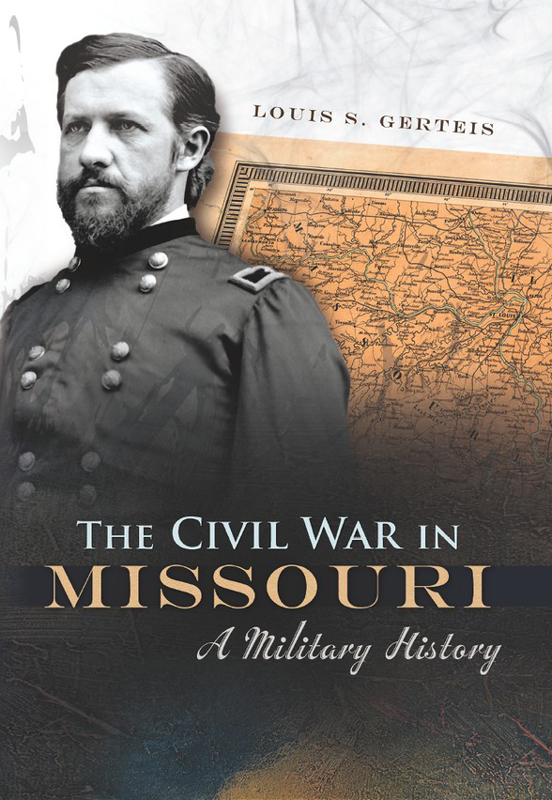

THE CIVIL WAR IN MISSOURI

A Military History

LOUIS S. GERTEIS

UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI PRESS

COLUMBIA AND LONDON

Copyright 2012 by

The Curators of the University of Missouri

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

5 4 3 2 1 16 15 14 13 12

Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8262-1972-5

ISBN 978-0-8262-7274-4 (e-book)

This paper meets the requirements of the

This paper meets the requirements of the

American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Design and composition: Jennifer Cropp

Printing and binding: Thomson-Shore, Inc.

Typefaces: Inscription, Minion, Engravers, and Trajan

IN MEMORY OF

JAMES NEAL PRIMM

MENTOR AND FRIEND

CONTENTS

PREFACE

In the history of the United States nothing rankles more than the tensions and enmities of the Civil War. In this military history of the war in Missouri, I have tried to offer a balanced account of the conflicts triumphs and defeats. At the same time I recognize that all histories are shaped by the perspectives and experiences of the historians who write them. Perhaps some observations about my own background will help to locate this work in a usable context.

I have dedicated this book to my late colleague James Neal Primm, an economic historian with a particular interest in banking policy. His knowledge of Missouri history was deep and wide, and in the arena of Civil War disputes and historiography, he was as surefooted as anyone I have known. Primm was from a Unionist family in Edina, in northeast Missouri, a region where proslavery and pro-southern sentiments clashed harshly with the free labor and northern-oriented interests of the regions commercial farmers and merchants. In the Unionist view, Missouri was not a southern state but an essential national corridor linking East and West. After World War II, Primm entered graduate school at the University of Missouri and studied history at a time when Revisionist historiography dominated interpretations of the Civil War Era. Among the most influential of the Revisionists was Avery O. Craven of the University of Chicago. Craven and the Revisionists generally downplayed the importance of slavery as a cause of the Civil War. More important were the irresponsible zealots on both sides of the sectional divide and the pandering politicians who empowered them. It was an interpretation of the Civil War that Primm understood but never accepted: he always knew that slavery was the cause of the war because his father told him that it was.

So it is with me. My interest in history and my understanding of the past are shaped by family memories. I was born in Kansas City, Missouri. Neither of my parents had immediate family ties to the Civil War, but the war was never very distant from our lives. My fathers German ancestors immigrated to the United States immediately after the Civil War and eventually settled in eastern Kansas. My mothers family moved into southwestern Missouri after the Civil War and settled in Neosho. My parents met and married in Kansas City where, I suspect, they believed they had left behind the parochial concerns of a distant sectional conflict. With the outbreak of World War II, my family moved to Arlington, Virginia, and my father began working for the federal government. In Arlington, the Civil War emerged from the landscape, and sectional identities informed social relationships. In the woods surrounding our apartment complex overgrown earthworks revealed the remains of the Civil War defenses of Washington, DC. Arlington House, Robert E. Lees mansion overlooking the Potomac, was close at hand, and the sites of the battles of Balls Bluff and Bull Run revealed the magnificent Potomac River valley and the rolling hills of the Virginia Piedmont rising to the distant Blue Ridge Mountains. My schoolmates who were native Virginians offered me a degree of acceptance because I came from a slave state. They were southern in sentiment and pointed out with pride that Baileys Crossroads (still a crossroads at the time) was the location of a skirmish during a daring raid by the Confederate partisan John Singleton Mosby.

During summers, my family frequently made automobile trips back to Missouri and Kansas. During one trip we visited friends of my mother in Neosho (at some point I learned that the town had been the Confederate capital of Missouri) before driving into eastern Kansas to visit an elderly aunt of my father. My great-aunt had been a longtime member of the Unitarian Church in Lawrence, Kansas, and remembered the congregations somber annual observance of William Quantrills murderous raid of August 1863. From her youthful memory my great-aunt retold terrifying stories shared with her by survivors. Before we left, I think it was at my mothers suggestion, my sisters and I sang to her what we knew of the Battle Hymn of the Republic.

My formal study of history began at Antioch College in 1960 and continued at the University of Wisconsin to 1969. For me the study of history coincided with the centennial of the Civil War and with the civil rights movement. I studied with historians who actively rejected Revisionist historiography and worked to recover a long-suppressed abolitionist narrative of the Civil War Era. It was in this intellectual climate that I had the opportunity to hear a lecture delivered by Avery O. Craven, retired from the University of Chicago at this point. At Wisconsin he offered a series of undergraduate lectures as a visiting professor. The topic of his lecture was the sectional bifurcation of the Democratic Party at its nominating convention in Charleston, South Carolina, in late April and early May of 1860. It was a critical moment in history, Craven said: if the Democratic Party could have maintained its institutional unity, in all likelihood Stephen A. Douglas would have been elected president and the Union would have been preserved. Tragically it was not to be. Craven constructed vivid descriptions of the passions of the moment as moderate men of sound principle were undone by zealots. Douglas failed to secure the requisite two-thirds majority of delegates after dozens of ballots. In frustration and anger, the partys northern and southern delegates dispersed. Craven lectured brilliantly but, for me, unconvincingly. For Craven the Civil War was an unmitigated tragedy that should have been avoided. In my experience the war was a catharsis: a bloody, brutal, epic, heroic struggle that changed the character of the nation. Writing about the war in Missouri has given me a fresh appreciation of the reasons the Civil War continues to rankle, and to fascinate.

Louis S. Gerteis

St. Louis, Missouri

January 6, 2012

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work began after a conversation some years ago with Clair Willcox, editor-in-chief of the University of Missouri Press. Willcox had long wanted to publish a one-volume military history of the Civil War in Missouri. The approaching sesquicentennial of the war seemed to offer a propitious occasion for such a project, and he asked me if I would be interested in undertaking it. I agreed, and as the project progressed I have benefited from the involvement of a number of individuals.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of the

This paper meets the requirements of the