While the authors have made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the authors assume any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication.

Most Tarcher/Penguin books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchase for sales promotions, premiums, fund-raising, and educational needs. Special books or book excerpts also can be created to fit specific needs. For details, write Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Special Markets, 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin a member of

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

www.penguin.com

Copyright 2003 by Center for Media and Democracy

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rampton, Sheldon, date.

Weapons of mass deception : the uses of propaganda in Bushs war on Iraq / by Sheldon Rampton and John Stauber.

p. cm.

Includes index.

Msr ISBN 0-7865-4591-7

Aeb ISBN 0-7865-4592-5

Making or distributing electronic copies of this book constitutes copyright infringement and could subject the infringer to criminal and civil liability.

book design by lovedog studio

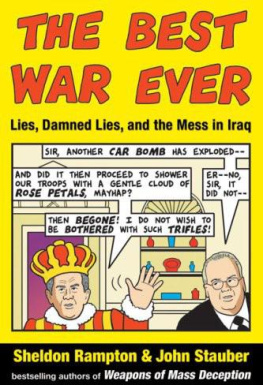

A LSO BY S HELDON R AMPTON AND J OHN S TAUBER

T RUST U S , W E RE E XPERTS !

T OXIC S LUDGE I S G OOD FOR Y OU !

M AD C OW U.S.A.

We thank our employer, the nonprofit educational organization Center for Media & Democracy, and the individuals and nonprofit foundations that have supported its work since 1993. This book is part of the Centers unique mission of investigating propaganda as it is waged by corporations and governments. For information on the Center, visit its website at www.prwatch.org, or contact its office: 520 University Avenue, Suite 310, Madison, Wisconsin, 53703; phone: (608) 260-9713.

Many thanks to our wonderful colleague Laura Miller, the associate editor of the Centers quarterly PR Watch, who has been like a third author of this book, contributing research and writing, especially in the chapters War Is Sell and Doublespeak.

Thanks especially to our editor Mitch Horowitz for his invaluable advice, encouragement and good sense. Thanks also to publisher Joel Fotinos of Jeremy P. Tarcher for the opportunity to write it. We thank John Kelly Groves, Tarcher/Penguin publicist, and Tom Grady, our wise agent and adviser.

The following organizations and individuals have helped us with ideas, comments, research and other support: Grant Abert, Asif Agha, Harriet Barlow, Aarick Beher, Laura Berger, Gordon Brand, Bob Burton, Joe Davis, Pamela Frorer, Grodzius Fund, Edward Goldsmith, Earl Hood, Linda Jameson, Jim Kavanagh, Oliver Kellhammer, Donna Balkan Litowitz, Robert Litowitz, Kevin McCauley, Laiman Mai, Marianne Manilov, Joe Mendelson, Dave Merritt, The Middle East Research and Information Project, David Miller, Gretta Wing Miller, Tim Nelson, Dan Perkins, Scott Robbe, Abby Rockefeller, Andy Rowell, Debra Schwarze, Paul Alan Smith, John H. Stauber, Chris Toensing, Nancy Ward, the Winslow Foundation, Walda Wood and Margie Zilic.

John thanks his colleague Sheldon for shouldering most of the burden of writing this book. John dedicates it to three activist friends who have passed on but whose inspiration remains: Alex Kurki, Billee Shoecraft and Tom Saunders.

A S U.S. TANKS stormed into Baghdad on April 9, 2003, television viewers in the United States got their first feel-good moment of the wara chance to witness the toppling of a giant statue of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

Americans channel-flipping over breakfast among Fox, CNN and CBS all saw the same images, broadcast live from Baghdads Firdos Square. For those who missed it in the morning, the images were continually replayed on cable news throughout the day, and newspapers carried front-page color photos.

A crowd of jubilant Iraqis had climbed onto the statue, thrown a noose around its neck and tried to pull it down. A man with a sledgehammer began pounding at its concrete base. Others took turns, but the statue was too big and the base too massive, so the U.S. Marines moved in with an armored vehicle and a chain. The soldiers had brought along an American flag, which they passed up to Private Ed Chin, the soldier working to affix the chain around Saddams neck. Chin draped the flag over Saddams face, but the gesture stirred a ripple of the wrong kind of feeling from the Iraqis. An Iraqi flag was found to replace the American flag. The crane began to pull, and Saddams statue first bent from its pedestal and then snapped completely, to roars of approval from the crowd, which surged forward to stomp on its remains, kicking and spitting on the rubble. Whooping, they dragged its head through the street.

In the months leading up to the invasion, pro-war commentators had predicted that the people of Iraq would greet American soldiers as liberators, and this scene seemed to prove them right. U.S. defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld compared the day to the collapse of the Iron Curtain. Saddam Hussein is now taking his rightful place alongside Hitler, Stalin, Lenin, Ceauescu in the pantheon of failed brutal dictators, and the Iraqi people are well on their way to freedom, he declared. Media commentators were also quick to assign iconic significance to the statues tumble, ranking it alongside the fall of the Berlin Wall, the protesters facing down tanks at Tiananmen Square and other great events caught on TV.

NBCs Tom Brokaw compared the event to all the statues of Lenin [that] came down all across the Soviet Union.

Iraqis Celebrate in Baghdad, reported the Washington Post .

Jubilant Iraqis Swarm the Streets of Capital, said the headline in the New York Times .

It was liberation day in Baghdad, proclaimed the Boston Globe .

USA Today ran a photo of the event on its front page, accompanied by an interview with Private Ed Chins sister, Connie. Its just amazing, were just so proud of him, she said.

If you dont have goose bumps now, gushed Fox News anchor David Asman, you will never have them in your life.

The Clash of Symbolizations

But there was also a self-conscious and forced quality to the images, observed the Boston Globe . Whenever the cameras pulled back, they revealed a relatively small crowd at the statue, wrote Globe reporters Matthew Gilbert and Suzanne Ryan. Los Angeles Times reporter John Daniszewski, who was on the scene to witness the statues fall, caught an aspect of the days events that the other reporters missed. Most Iraqis were indeed glad to see Saddam go, he wrote, but he spoke near the scene with an Iraqi businessman, who warned that Americans should not be deceived by the images they were seeing.

A lot of people are angry at America, the businessman said. Look how many people they killed. Today I saw some people breaking this monument, but there were peoplemen and womenwho stood there and said in Arabic: Screw America, screw Bush. So all this is not a simple situation.

The visual images, of course, are what most people will remember. Most Americans, including the 300,000 soldiers who risked their lives, genuinely believed that Operation Iraqi Freedom was a noble cause and that they were helping make the world a better, safer place for themselves and their loved ones. But it is worth asking whether the toppling of the statue of Saddam was as spontaneous as it was made to appear. If this scene seemed a bit too picture-perfect, perhaps there is a reason. Consider, for example, the remarks made by public relations consultant John W. Rendonwho has worked extensively on Iraq-related projects during the past decade on behalf of clients including the Pentagon and the Central Intelligence Agencyon February 29, 1996, before an audience of cadets at the U.S. Air Force Academy.

Next page