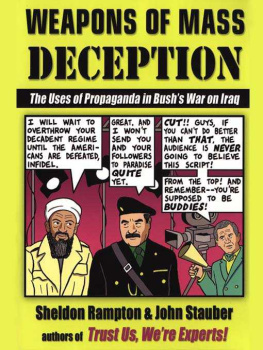

I F IT IS TRUE that generals have a tendency to fight the last war, so too do antiwar protesters. While there was certainly room for serious debate about the wisdom of engaging in war with Iraq, many observers were struck by the incongruity of some of the positions taken in opposition to the war. On the one hand there was the frightening, if unfounded, image of indiscriminate U.S. bombing causing thousands (or even hundreds of thousands) of civilian deaths; on the other hand it was rarely acknowledged that the existing state of peace already entailed very real civilian suffering, without any hope of relief, as well as a substantial (and widely resented) U.S. military presence in the Persian Gulf region that could not be withdrawn until the threat had been eliminated.

Most striking, however, was the easy dismissal, on the part of many commentators as well as protesters, of the idea that U.S. policy-makers might have serious concerns about an Iraqi threat, either imminent or long-term. President George W. Bushs commitment to disarming Iraq was seen as reflecting (pick one): his cowboy mentality; or his ties to big oil; or the pernicious influence of his hawkish neoconservative advisers. The war against Iraq was treated as a distraction from the war on terrorism, rather than as a key element of it.

Dismissing the Threat

S OME OF THE criticisms had the quality of wishful thinking. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace assured us that we neednt fear biological or chemical terrorism because Saddam could be counted on not to share his crown jewelshis weapons of mass destructionwith terrorist agents. Along the same lines, others held that he would unleash such weapons only if he faced certain military defeat.

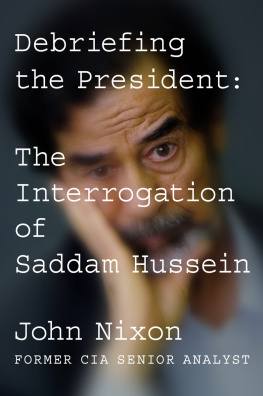

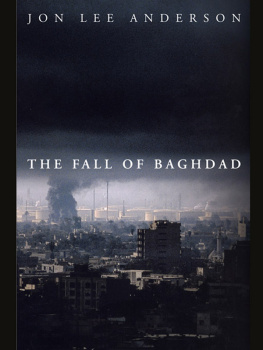

It is hard to imagine any president staking the security of American cities on reasoning of this sort. For President Bush, the first duty of the office was to protect the countrys security. He certainly did not have the option of ignoring the strategic landscape: Saddam Husseins project included his unrelenting push to develop and conceal weapons of mass destruction; his use of chemical warfare during the 1980s; his successful drive to end weapons inspections in the 1990s; his blatantly imperialist aspirations, invading first Iran and then Kuwait and threatening Saudi Arabia too (not to mention raining thirty-nine missiles down on Israel); and his avowed hostility to the United States throughout the period since the 1991 Gulf War.

Nor could any policy-maker, particularly after September 11, 2001, disregard the possibility of innovative, nonmilitary methods of delivery of chemical or biological weaponsbotulism, smallpox, or deadly nerve agents such as sarin, mustard gas, or VX. Anthrax, after all, had arrived through the mail, and passenger planes had become deadly missiles.

This seems an obvious enough point, so obvious that its difficult to understand why so many commentators not only dismissed such concerns, but also could not fathom that anyone actually took them seriously.

The Party Is So Over

I TS HARD TO RECALL just how giddy and dizzying the 1990s were. We had won the 1991 Gulf War handily, finally laying to rest (it seemed) the ghost of Vietnam. The Soviet Union, our great antagonist, suddenly collapsed from its own inner weakness. Bill Clinton ranand wonon the slogan Its the economy, stupid, and the longest period of sustained economic growth in U.S. history followed. America had peace and prosperity.

Both the peace and the prosperity contained elements of illusion, we now recognize. The security bubble burst in one day, with the attacks of September 11, 2001. The economic bubble was already deflating, more gradually. The stock market decline, which began in 1999, deepened over the next year and a half; the dramatic rebound of the second half of 2001 turned to a full rout at the beginning of 2002, no doubt exacerbated by the economic fallout from the terrorist attacks. The bankruptcies of such established companies as Enron and WorldCom introduced the term creative accounting into the American lexicon and shook our faith in U.S. business leadership, as did the evidence that a number of prestigious Wall Street brokerage firms had been flogging overvalued shares of the corporations they brokered, making hefty commissions at the expense of their credulous clients.

The illusory peace bubble had something in common with this inflated impression of prosperity. As well see in , many of the members of U.S. government foreign policy agenciesthe bureaucracies-tend to serve interests as narrowly defined as those of the Wall Street brokerage firms. The interests of the public must be championed by elected officials, since such interests rarely register on the radar screens of unelected bureaucrats.

Where Were the Checks?

I N SOME WAYS, Americas Founding Fathers held a rather pessimistic view of human nature. Because they believed that power was bound to be abused, they established a system of government in which power is fractured, in a set of opposing forces we know as checks and balances. It is no great surprise to learn that some individuals or agencies in Washington have been prone to behavior comparable to Wall Streets sins of commissionand that such behavior can have an impact on the public interest and on national security. Ironically, though, individuals in the private sector are far more likely than those in government to be held to account for egregiously inappropriate behavior, even though the consequences of government officials actions can be much more damaging.

Everyone must do what he must do for his career, I was told by a highly regarded Middle East expert back in 1998. The times are very cynical, he claimed, and so behavior that was very self-serving became acceptable, irrespective of its possible implications for the countrys security. Like most of his colleagues at the time, he evidently shared the mentality of the now-disgraced Wall Street firms. And the cynically constructed policy analysis offered by most of the Iraq experts during the 1990s directly reflected the entrenched cynicism of the bureaucracies, which is where the greatest problem lay.

The Decision for War

T HE DECISION FOR WAR with Iraq was made soon after the September 11 attacks, far above the bureaucratic level.

On September 17, 3001, following a weekend meeting with his senior advisers at Camp David, Bush told a National Security Council meeting, I believe Iraq was involved, but Im not going to strike them now. I dont have the evidence at this point. Bush had already decided to target Osama bin Laden, al Qaeda, and the Taliban, but he also told the Pentagon to keep working on plans for attacking Iraq, and he signed off on the outline of a war plan that included Iraq.