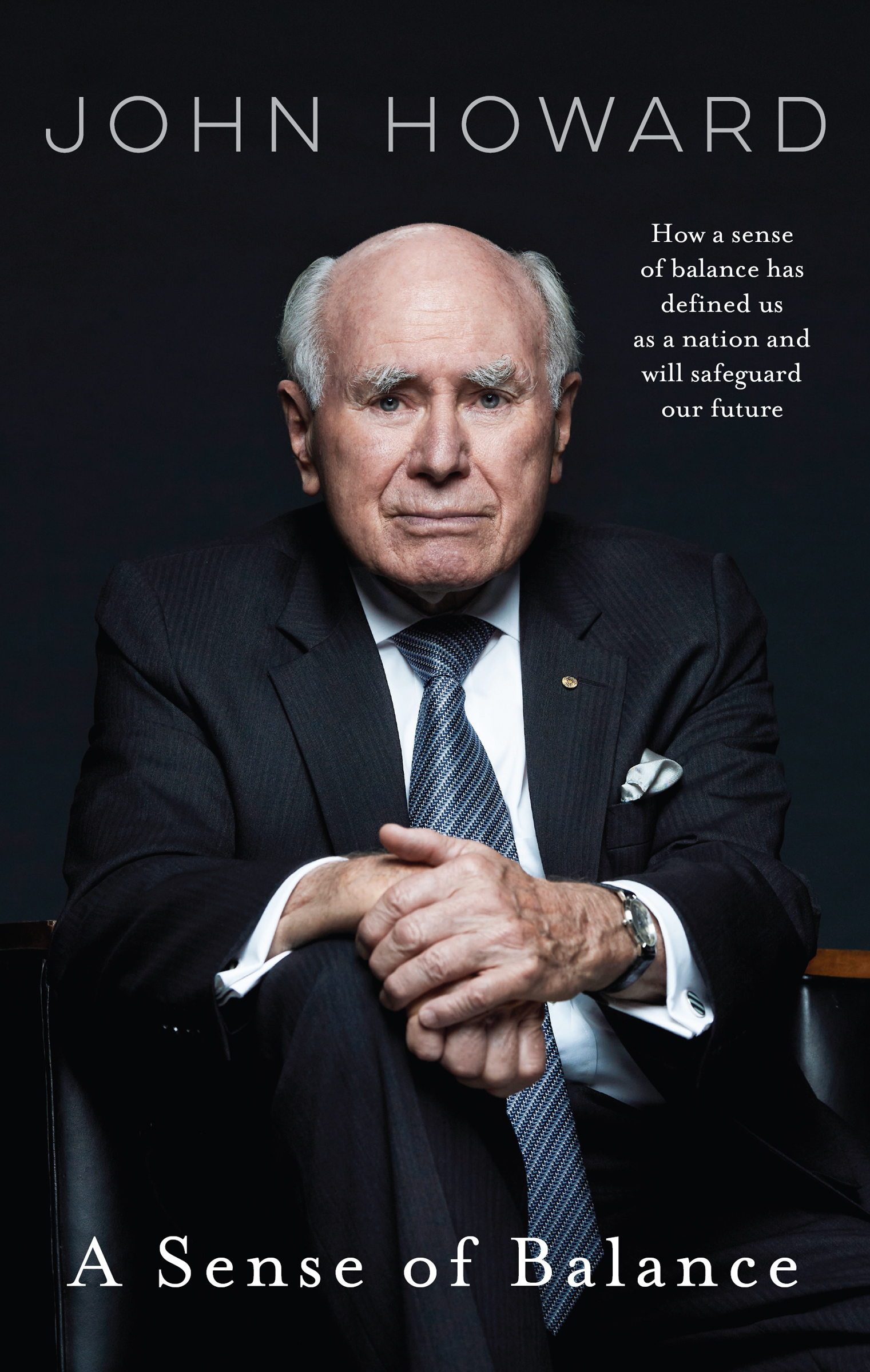

John Howard - A Sense of Balance

Here you can read online John Howard - A Sense of Balance full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Sense of Balance

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sense of Balance: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Sense of Balance" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

John Howard: author's other books

Who wrote A Sense of Balance? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

A Sense of Balance — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Sense of Balance" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To my grandchildren, with the hope that Australia is

as good to you as it has been to me

Australia has been kind to me, as it has to almost all who have been born in this blessed country, or have chosen to live here.

It is not white triumphalism to celebrate The Australian Achievement. That was the designation assigned by the Fraser Government in 1981 to the bicentennial celebrations due to take place in 1988. It was a way of expressing quiet pride in what our nation had become: an essentially classless, economically self-reliant, wholly independent liberal democracy. A nation that sat comfortably at an intersection of history, geography and culture: profoundly Western in its civilisational background; increasingly immersed in the politics and economics of its immediate neighbourhood; warmly embracing its relationship with its major ally the United States, but always a citizen of the world that had long practised an open and non-discriminatory immigration policy. With the passage of time, I have grown ever more comfortable with The Australian Achievement as a positive and eloquent, yet not overblown, description of our nation.

Yet in 1988, Australia still struggled to find the right way to honourably place its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within the mainstream of the nation. There was a largely united view that the First Australians were a disadvantaged group, and that more had to be done to remedy this. They had suffered prejudice and discrimination, which represented the greatest blemish in our national story. There were those who subscribed to what I would later call practical reconciliation. Their focus was on improving the educational, health and housing opportunities for Indigenous people, thereby achieving a quantum lift in their employment outcomes. In this way they could truly become part of mainstream Australia. Others were obsessed with re-adjudicating the past. To them it was all about guilt and dispossession.

Those different approaches largely continue. Most Australians then (as now) wanted to improve the lot of Aboriginal people; consistent with that, they valued the fact that they were part of Western civilisation, and knew that but for British settlement the modern, vibrant and free nation they loved and enjoyed would not have come about.

In the 18th century, colonisation of the Australian mainland by a European power was next to inevitable. The British colonisation of Australia had many flaws, yet there is much in the assertion that the best thing that ever happened to Australia was to have been settled by the British.

We owe a lot to our British origins: the commonality of institutions, language, legal systems, press freedoms, sporting passions, in some respects our sense of humour, and so the list goes on. Yet we drew the line very early. Australians rejected class distinctions or any semblance of an aristocracy. These things were judged to be out of step with the distinctive society we had begun to build. Respect was never to morph into deference. Australia had chosen the good bits of our British inheritance, but rejected the bad bits, and the bits that were simply not fit for purpose.

This was an early illustration of what would grow to be one of the defining characteristics of our nation, and that was a sense of balance. I have chosen this phrase as the title of this volume, because it deals with topics in our current national discourse in which that sense of balance shines through.

The Hawke Government was in power when the bicentennial celebrations finally took place, and in an early act of cancel culture an unknown expression in the 1980s it discarded The Australian Achievement in favour of the empty and limp tag of Living Together. Not entirely clear about what the bicentenary should be celebrating, the government replaced a positive affirmation of what Australia had achieved in 200 years with a meaningless banality.

The major formal event of the 200th-anniversary party was at Sydney Cove on 26 January, addressed by the PM and Prince Charles. Right on song, it was interrupted by the arrival of the First Fleet re-enactment, which by then had become a private-enterprise venture. The government could no longer handle the sponsorship of what had begun as an official re-enactment of Phillips epic First Fleet voyage that inaugurated modern Australia.

Some Aboriginal people objected to the bicentennial commemoration, consistent with their argument that Australia had been invaded. Wishing to accommodate Aboriginal opinion, and goaded by leftist apologists, who seemed ashamed of what Australia had become, the government separated itself from the re-enactment, secure in the knowledge that plenty of Australians, proud of what we had achieved, would pitch in to ensure that the expedition would not fail. But in a final act of hypocrisy, the official program for the day was arranged so that there was a gap to accommodate the arrival of the First Fleet re-enactment. Neither out of sight nor out of mind, but certainly out of official acknowledgement. Little was made of this at the time. Australians knew there was plenty about their country to celebrate.

Debate about 26 January as Australia Day continues. In this context it is worth noting that, in its historic Mabo judgement four years later, widely hailed as a landmark in achieving proper recognition of the First Australians, the High Court of Australia did not question that Australia had been settled, as distinct from being either conquered or ceded. Mr Justice Toohey stated, inter alia: There is no question of annexation of the [Murray] Islands by conquest or cession, so it must be taken that they were acquired by settlement even though, long before European contact, they were occupied and cultivated by the Meriam people.

During the years that I served in the national parliament I came to further understand the special character of our country; to appreciate its strengths and weaknesses; and most importantly to respect that sense of balance in the formulation of public policy that has long defined us as a people.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the area of social-welfare provision, where Australia well and truly occupies the sweet spot. Our treatment of the genuinely disadvantaged both avoids the harshness of the American approach and eschews the paternalism adopted in many European countries, which discourages self-reliance and robs labour markets of the flexibility so important for economic efficiency.

One expression of this sweet spot is found in how the government and private sectors interact with one another in relation to both health and education. A feature of Australias very successful response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been the relatively seamless way in which the public and private elements of our health system have joined forces. It was starkly obvious from the beginning that the success of contact tracing would be crucial in the fight against COVID, so state public health authorities have masterminded on-the-ground responses. The relative success of New South Wales in this endeavour speaks volumes for the efficiency of its decentralised yet tightly coordinated health system. Private hospitals stood ready to provide additional care capacity when needed.

Vaccination has been carried out with like cooperation. GPs and pharmacists have provided the willing community backbone, augmented by mass vaccination hubs. Governments have controlled the procurement of vaccines and provided control and guidance as to priority groupings.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Sense of Balance»

Look at similar books to A Sense of Balance. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Sense of Balance and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.