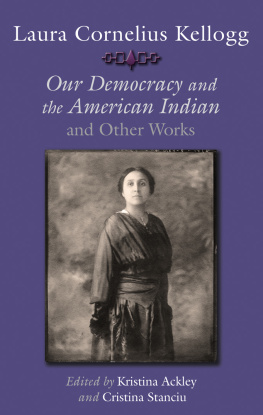

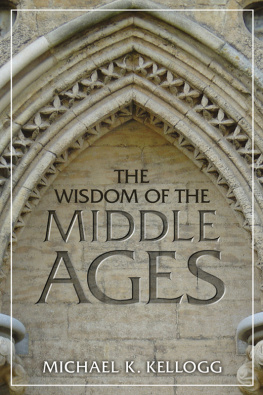

Frontispiece, first edition,

Our Democracy and the American Indian

(Burton Publishing, 1920).

All royalties from the publication of this book will go to the Cultural Heritage Department, Oneida Nation in Wisconsin.

Parts of the introduction originally appeared as Laura Cornelius Kellogg, Lolomi, and Modern Oneida Placemaking by Kristina Ackley and An Indian Woman of Many Hats: Laura Cornelius Kelloggs Embattled Search for an Indigenous Voice by Cristina Stanciu in a special issue on the Society of American Indians, American Indian Quarterly 37, no. 3: 11738; SAIL: Studies in American Indian Literatures 25, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 87115. Reprinted with permission of University of Nebraska Press, publisher of both journals.

The introduction contains unpublished material from the Ernie Stevens, Sr. Collection, located at the Division of Land Management, Oneida Nation in Wisconsin.

Overalls and the Tenderfoot, originally published in The Barnard Bear 2, no. 2 (March 1907). Reprinted with permission of Barnard Archives and Special Collections.

Copyright 2015 by Syracuse University Press

Syracuse, New York 13244-5290

All Rights Reserved

First Edition 2015

15 16 17 18 19 20 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

For a listing of books published and distributed by Syracuse University Press, visit www.SyracuseUniversityPress.syr.edu.

ISBN: 978-0-8156-3390-7 (cloth) 978-0-8156-5314-1 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Available from publisher upon request.

Manufactured in the United States of America

For our parents, children, and the Oneida Nation

Kristina Ackley, PhD, is a tenured member of the faculty in Native American studies at The Evergreen State College. A citizen of the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin, she received her PhD in American Studies from the State University of New York at Buffalo, and her MA in American Indian law and policy from the University of Arizona, and was a postdoctoral fellow in American Indian Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Kristina has published her work in American Indian Quarterly, Studies in American Indian Literature, American Indian Culture and Research Journal, and edited collections. She generally teaches in programs that prepare students for work in the fields of education, government, law, social services, and public history. Kristina is at work on a book manuscript on Oneida placemaking.

Cristina Stanciu is an assistant professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University, where she teaches courses in American Indian studies, US multi-ethnic literatures, and critical theory. Her work has appeared and is forthcoming in American Indian Quarterly, Studies in American Indian Literatures, MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States, College English, Wicazo Sa Review, Intertexts, Film & History, Chronicle of Higher Education, and edited collections. Cristinas research on her current book projectThe Makings and Unmakings of Americans: Indians and Immigrants in American Literature and Culture, 18791924has been supported by fellowships at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, and the Newberry Library, Chicago.

Contents

Contents

Guide

Illustrations

Foreword

L aura Miriam Cornelius was born in 1880 in a log home on a trail in the center of the Oneida Indian Reservation. The trail was to become Old Seymour Road and Laura was to become known as Laura Minnie Kellogg. It was a time of extreme conflict between the Oneida Nation and the United States of America on the issue of allotment, a process of allotting parcels of tribal property previously held in common to individuals of the tribe. Therefrom sprung confusion and conflict among various parties of Tribal members, who held strong opinions as to their future survival. Laura grew up surrounded by family members, friends, and leaders in the Oneida Community who were in constant debate as to what course of action would be in their best interest.

Now, at long last, 135 years from her birth, we have this opportunity to view her thoughts and motives. There is much in her work to review and contemplate, for her words and inspirations may be as appropriate now, or even more so, than they were at the time she wrote or said them.

Cristina Stanciu and Kristina Ackley have reviewed her works and recognized her genius, with the consideration that Laura is a Native American woman of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when womenespecially Native womenwere not recognized throughout the general population for national and worldwide leadership qualities.

Laura Minnie Kellogg did everything in her power to assist her own tribe, the Oneidas, to overcome all the diseases, effects of wars, removal from their homelands, and loss of homes and large land masses. She urged her fellow tribesmen and women to learn the system available to them to address their grievances and wrongs. She did this eloquently.

It is time, now, thanks to the research and editorial work of professors Stanciu and Ackley, to learn what Laura Kellogg is continuing to teach us, Native people as well as non-Natives: that the improved welfare of certain original populations of this land prevails and elevates the status of us all.

This work is timely in that tribal members need to reflect on their histories to come to grips with their present circumstances. One area among many current difficulties relates to the need for tribal populations to escape desperate poverty and to obtain regular incomes, and the need to replace structures lacking running water and electricity with adequate and livable housing. Those having difficulty in their present circumstances can look to Laura for words of encouragementwords they can live by 100 years later.

January 14, 2014

Loretta V. Metoxen

Oneida Tribal Historian

Preface

Senator Curtis, I want to ask: What is the objection to keeping an Indian an Indian provided he is a better Indian than he is a white man?

Laura Cornelius Kellogg to

Senator Charles Curtis, 1916

L aura Cornelius Kelloggs astute and politically loaded questionwhy not keep an Indian an Indian?evokes, in many ways, her legacy as an Oneida leader and as an American Indian intellectual of the early twentieth century, a time when Native people in the United States faced incredible pressures to assimilate as individuals into American society. The largest barrier to the agenda of assimilation was the common land base that sustained a tribal sense of identity and which represented the most visible sign of Native persistence. Allotment, which broke up the reservations into individual landholdings and opened any surplus land to sale and development, was reaching its zenith at this time; a parallel movement followed, signaling the failures of the policy and working on behalf of tribal communities to determine their futures. Native people did not universally agree on the best way to achieve this goal. Some believed that emancipating the Indian from federal supervision (many would say paternalistic control) would foster self-sufficiency and would alleviate social dysfunction and economic challenges that plagued many reservations; others argued for an increased emphasis on tribal identities, with extensive resources directed toward the reservation to combat the same problems.