In the Name of the People

Liaisons

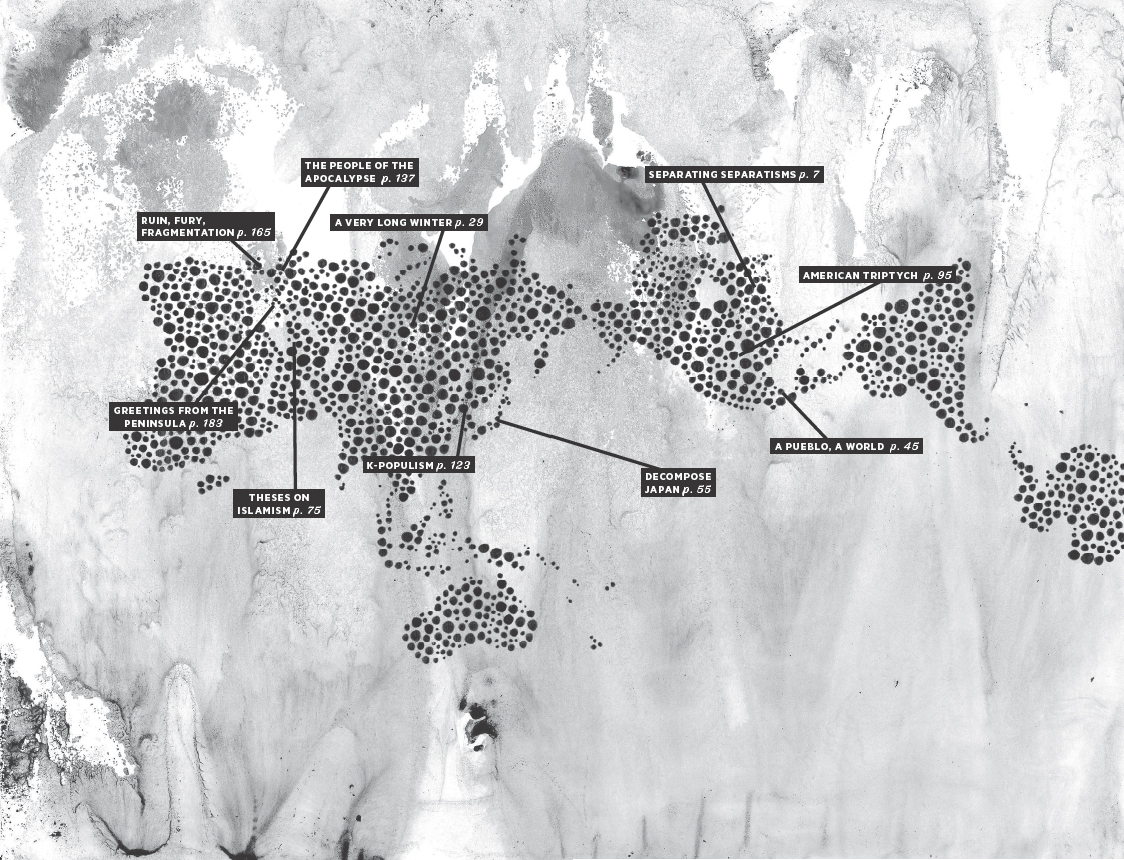

Transoceanic Partisan Research

This edition 2018 Common Notions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

ISBN: 978-1-942173-07-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018944086

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Liaisons

In the Name of the People features a number of paintings (19921993) by Ben Morea, publisher of Black Mask (19661968) and a member of the Up Against the Wall/Motherfuckers (19681969).

Common Notions

314 7th St.

Brooklyn, NY 11215

www.commonnotions.org

Cover design by Josh MacPhee/Antumbra Design

Layout design and typesetting by Morgan Buck/Antumbra Design

www.antumbradesign.org

Printed in the USA by the employee-owners of Thomson-Shore

www.thomsonshore.com

I n Liaisons, an old dream reemerges from the depths. After years of elaborations, debates, connections, and political artifacts, our transoceanic endeavor takes form. We have found friends with whom we share a sensibility and a similar way of asking questions: How can we construct alliances without compromising what we hold close? How can we make room for different sensibilities without succumbing to moralism? How can we hold together urban struggles and rural autonomy? Certain subterranean affinities demanded a common place, a sounding board, a planetary reverberation.

The very hour the world returns to us as a dramatic unity through its own dissolution, the horizon of a humble international takes form. This is recognizable by way of a series of familiar developments: the multiplication of riots against the police, the generalized desertion of institutions, the blockade of nuclear and gas infrastructures, the proliferation of zones to defend, and the commoning of the means of life and resistance. Everywhere an awakening of political vitality and strategic perception, everywhere wanting to have it out once and for allno longer with the world, but with its end.

We came of age in an age of separations, prisoners of an end-nearing time. Our political heritage is preceded by no testament, and this is all the more true of a world being devastated to the last gram. In the sixteenth century, one spoke of disaster to designate the loss of a connection with the stars, as both points of reference and of influence. A few centuries later, D.H. Lawrence would make of this the cause of his and his contemporaries solitude. They had, he wrote, lost the cosmos. We lack neither humanity nor personality; what we lack is cosmic life, the life of the sun in us and the moon in us. The stars, by all appearances, have only dimmed since then. We find ourselves today thoroughly de-starred, ds-astrs.

In this context, the last of possible disasters is to believe they could all somehow be overcome. Such is the mirage of the populist, who comes to bring the situation under control, and just in time. Everyone was surprised by the victory of Trump, while Putin, Berlusconi, Erdogan, Modi, and Netanyahu have reigned for years in the same register. Whether they hail from popular roots or have just acquired the style, this group exhumes that so-called alliance between the sovereign and his People. They create the appearance of a gap on the other side of which the elites take refuge, huddled together under the obscure light of the deep state. These new populists won hearts with the promise to safeguard all that, in the People, is identical to itself, in order to raise it, in unison, against the menace of the ethnic, sexual, or political minoritya gesture which often seems to extend to the point of including, at one moment or another, almost everyone. From the entrails of these masses long wandering in the neoliberal desert, they resurrect a new People of resentment.

We seem to have passed from a regime of war through pacification to one of war itself, almost without knowing it. Such a situation threatens to remove us from the agenda of things to come, of what counts or not, of what polarizes or evokes indifference. The enemy, no longer confined to capitalist dispossession, set foot at our door, threatening to pull the rug out from under our feet. The enemy sought to capture the very energies of opposition to the liberal order, to put them at the service of a governmental machine uninhibited of any sense of social acceptability. Far from bringing the refined techniques of governance of the society of control to an end, the new autocrats merely added a new helping of brutality. Justice openly conspired with the alt-right to shut down antifascists in the United States, the image of antifascist resistance was mobilized to maintain a hyperreal war in the Ukraine, and emergency laws were even established to suspend the French constitution. And all this happened in the name of the People.

In the face of this convocation of the people at the altar of the Nation, the movements that rise up in response are also characterized as popular, for want of more clear determinations. It is nevertheless clear, for example, that the effervescence of the Arab Spring or the French movement against the El Khomri law were largely due to the decay of unions and other classic organs of mobilization. Even at the podium of Nuit Debout in France, as with the Spanish indignados or Occupy in the United States, the meticulously articulated, formally democratic call to the People, crying out in the name of a totality, finally shattered through its own exhaustion.

We have seen, once the winds of the movement of the squares ran out of breath, new leftist populist machines rush onstage in a last attempt to save the good from the bad people. We have seen the capture and channeling of popular angerfor the benefit of a kingdom without foundation nor imaginationcollapse in real time. And the enthusiasm evoked by Syriza, Podemos, or Bernie Sanders for the prospect of a People supposed to suddenly awake from its anomie, take hold of itself again and reconstitute a heroic figure by bringing down the rising fascist beastwe have seen all this perish in a simple vote. Once again, the People have spoken.

All this makes one wonder whether the figure of the People still has anything to say to us, or if we should finally let it die in peace. For Marcello Tar, the People will remain absent as long as this present is in force. For now, the breach opened by revolt offers one of the few ways in which this lack can appear in the world, if only for the duration of a flash. It is really only these brief flashes, short durations of enthusiastic contagionwhere the cruel absence of something like a People becomes the most glaringthat keep us from the postmodern cynicism so pleasurably proclaiming the end of every possibility.

If revolution is important to us, it is not in hopes of a new redistribution of riches or territorial control. Far from any discourse on political method, the age hardly leaves any choice but to think a revolutionary existence without subject, project, or heritage, including that of the people. In a certain way, it consists of recognizing the failure of politics as we have always known it, even the politics we have loved. But an admission of failure is not an admission of impotentiality. Power designates that which has not yet come to light, and is up to us to bring into being. Liaisons desires to contribute to this task by opening a plane of transoceanic, partisan research. For Friedrich Schlegel, a dialogue is always a chain or garland of fragments, and the intimate alterity of distant friendships is undoubtedly the best means of finding oneself againby way of another.