Poll Power

JUSTICE, POWER, AND POLITICS

Coeditors

Heather Ann Thompson

Rhonda Y. Williams

Editorial Advisory Board

Peniel E. Joseph

Daryl Maeda

Barbara Ransby

Vicki L. Ruiz

Marc Stein

The Justice, Power, and Politics series publishes new works in history that explore the myriad struggles for justice, battles for power, and shifts in politics that have shaped the United States over time. Through the lenses of justice, power, and politics, the series seeks to broaden scholarly debates about Americas past as well as to inform public discussions about its future. More information on the series, including a complete list of books published, is available at http://justicepowerandpolitics.com/.

Poll Power

The Voter Education Project and the Movement for the Ballot in the American South

Evan Faulkenbury

The University of North Carolina Press CHAPEL HILL

2019 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in MeropeBasic by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Faulkenbury, Evan, author.

Title: Poll power : the Voter Education Project and the movement for the ballot in the American South / Evan Faulkenbury.

Other titles: Voter Education Project and the movement for the ballot in the American South | Justice, power, and politics.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2019] | Series: Justice, power, and politics

Identifiers: LCCN 2018043542| ISBN 9781469651316 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469652009 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469651323 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Voter Education Project (Southern Regional Council) | Voter registrationSouthern States. | Civil rights movementsSouthern States.

Classification: LCC JK 2160 . F 38 2019 | DDC 324.6/40975dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018043542

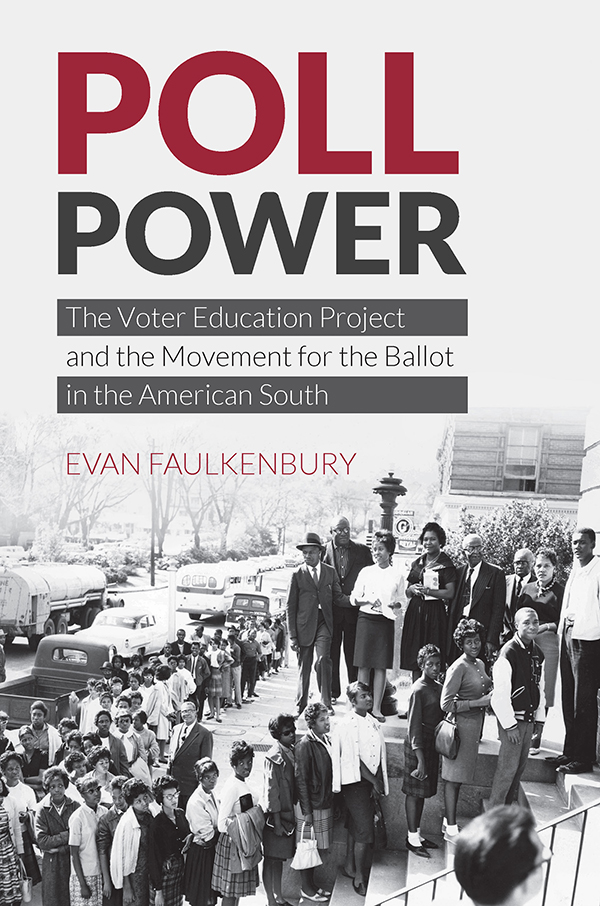

Cover illustration: Large crowd standing in line waiting to vote, circa 19601964. Voter Education Project Organizational Records, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library.

Portions of this book were previously published in a different form as Preventing a Second Redemption: The Voter Education Project and Black Elected Officials, 19661968, Southern Historian 36 (Spring 2015): 2434.

For Alex and Clara

Contents

Abbreviations in the Text

CIC

Commission on Interracial Cooperation

COFO

Council of Federated Organizations

CORE

Congress of Racial Equality

DOJ

U.S. Department of Justice

ICC

Interstate Commerce Commission

IRS

Internal Revenue Service

MFDP

Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

MIA

Montgomery Improvement Association

NAACP

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

NCVEP

North Carolina Voter Education Project

NUL

National Urban League

SCLC

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

SNCC

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

SRC

Southern Regional Council

SVREP

Southwest Voter Registration Education Project

VEP

Voter Education Project

VOTE

Voters of Texas Enlist

Mapping the Voter Education Project

The Voter Education Project supported hundreds of projects across the American South, and most did not make it into this book. Instead of dozens of tables and graphs within these pages to identify each one, I decided to create an online map representing each VEP-backed campaign between 1962 and 1970. Designed by AUUT Studio, this digital public history map displays as much data as I could find. In ways that words cannot do alone, this map illustrates the scale and impact of the VEP on the southern black freedom movement. I hope this map will lead to additional research. Most local projects have yet to be explored and written about in depth. http://mappingthevep.evanfaulkenbury.com

Poll Power

Introduction

In 1962, James McPherson, a retired postmaster in his late seventies, helped start a registration movement in Orangeburg County, South Carolina. It would be fair, wrote Randolph Blackwell, the field director for the Voter Education Project (VEP), to say that Mr. McPherson is effective in what he is doing.

Meanwhile, as the Orangeburg movement organized, VEP headquarters buzzed with activity. Within a small space on Forsyth Street in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, a handful of staff managed hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants from philanthropic foundations. The VEP collected and disbursed the money to voter registration projects across the American South. Inside the VEPs office, typewriters clacked while stacks of mail came in and out each day. A complex filing system tracked the finances and registration figures from community projects in almost a dozen states. The executive director oversaw a small team of researchers and office staff that solicited philanthropic funds, managed bank accounts, reviewed grant applications, mailed checks, visited projects, and compiled data on black disfranchisement. VEP staff regularly communicated with leaders from dozens of projects. To receive VEP money, organizers had to account for expenditures and report back to the VEP about how many people had registered or tried to register within a period. And grant recipients shared storiesnarrative reports of their battles against registrars, police, politicians, vigilantes, and everyday white southerners who knew that black voting would fracture the racial caste system. Day after day, month after month, the VEP aided grassroots freedom movements, like in Orangeburg, and in return, the VEP compiled information about voting rights, white supremacist resistance, strategies that worked, and tactics that did not. If a visitor had walked into the VEP office in Atlanta on any given day, the view would have been unremarkable: an average, cramped office with desks, chairs, telephones, typewriters, filing cabinets, coffee pots, and stacks of paper covered with tables, numbers, and percentages. But within this office existed the behind-the-scenes engine of the southern freedom movement, an organization hidden from popular view in order to work efficiently without media attention, to finance as many voter registration projects as possible, to study the causes of black disfranchisement, to find remedies and strategies to fight Jim Crow at the ballot box, and to win back black political power.

Dr. Charles H. Thomas Jr., an economics professor at South Carolina State College in Orangeburg, applied for his communitys first VEP grant in the summer of 1962. He knew that the desire to vote was strong in his county, though few black citizens had been able to register. African Americans had limited resources to orchestrate a prolonged freedom movement. While churches passed offering plates and the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) chapter held fund-raisers, sustaining a blitz on the registrars office proved time consuming and costly. Fuel for vehicles required money. Paying bills, rent, speaker fees, and salaries added up. To implement a successful drive, one that could maintain the energy of Orangeburgs black community against the countys intractable white political structure, money was crucial. On August 19, Thomas received good news that the VEP had awarded $5,000 for a three-month registration operation in Orangeburg.