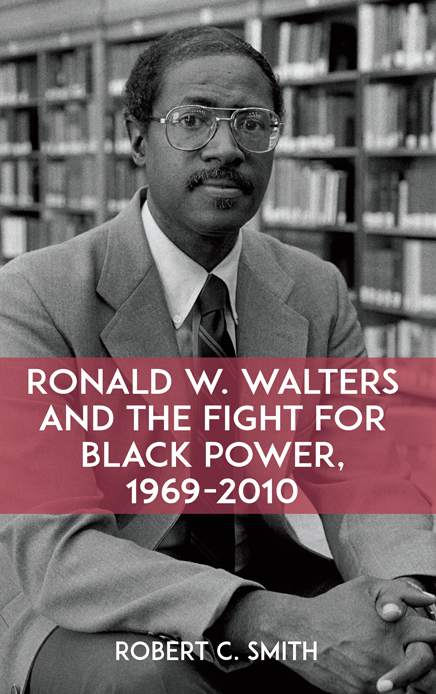

RONALD W. WALTERS

AND THE FIGHT FOR

BLACK POWER,

19692010

SUNY series in African American Studies

John R. Howard and Robert C. Smith, editors

RONALD W. WALTERS

AND THE FIGHT FOR

BLACK POWER,

19692010

ROBERT C. SMITH

Cover photo provided by the Ronald and Patricia Walters Family Archive (all photos

in the book from Walters Family Archive).

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2018 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Diane Ganeles

Marketing, Anne M. Valentine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Smith, Robert C. (Robert Charles), 1947 author.

Title: Ronald W. Walters and the fight for Black power, 1969-2010 / Robert C. Smith.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, 2018. | Series: SUNY series in African American studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015614 (print) | LCCN 2017015952 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438468686 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438468679 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Walters, Ronald W. | African American political activistsBiography. | Black powerUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Black powerUnited StatesHistory21st century. | United StatesRace relations.

Classification: LCC E185.97.W1343 (ebook) | LCC E185.97.W1343 S65 2018 (print) | DDC 322.4092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015614

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Greyson Robert Rutland

Contents

Chapter 11 Black Power and Democracy in America:

The Ultimate Paradox

Chapter 12 Ronald Walters and the Long Black

Intellectual Tradition

Acknowledgments

This book could not have been written without the assistance of two women. First, Mrs. Ronald Walters, who not only allowed me to stay in her house and review her husbands papers, but engaged in multiple email correspondences and telephone conversations that enhanced my understanding of Rons life and work. She was also indispensable in helping me arrange the interview with Reverend Jesse Jackson. The second indispensable person was my wife, Scottie. As with all that I have written, she was the careful critic, editor, and typist. I am much obliged to both of these extraordinary women.

Partly because of my closeness to Walters and concerns about my objectivity, I asked an unusually large number of persons to review the manuscript. I am grateful to the following good colleagues for their time and critical analysis and useful suggestions: David Covin, John L. Johnson, Mack H. Jones, John R. Howard, Wilmer Leon, Sekou Franklin, Marion Orr, Errol Henderson, and William Strickland. The anonymous reviewers were knowledgeable of Walterss work and made critical comments and suggestions that were valuable in the revisions. Michael Rinella and the editorial and production staffs at SUNY did their usual exceptional work in arranging reviews of the manuscript and preparing it for publication. Finally, I should like to thank Dr. Elsie Scott, the Director of the Ronald Walters Leadership and Public Policy Center at Howard, for reading the manuscript and writing the foreword.

I dedicate this book to my thirteen-month-old grandson, hoping that when he reads it he will be inspired to contribute to the liberation of black people and to become a perfect Black Power man.

Foreword

Ronald W. Walters and the Fight for Black Power, 19692010 is a political and intellectual biography rather than a traditional personal biography. Robert Smith probably chose not to make this biography a personal biography because Walterss political and intellectual lives were so much a reflection of him as a person. Although the book is not a personal biography, Smith gives background on Walterss family to help the reader understand the foundation for Walterss activism and independence.

Smith is the person most qualified to write about Walters as a political and intellectual being because he was not only a student of Walters, but some say he was Walterss favorite student. Patricia, Walterss wife, has remarked that Smith knew the intellectual side of Walters better than anyone. In addition, Smith and Walters collaborated on several projects, including the seminal book, African American Leadership , published in 1999.

This book tells Walterss story by walking the reader through a history of black intellectual life and the black movements from the Civil Rights era through the election of the first African American President of the United States. It is a valuable read for those who lived through this period of history, but it is invaluable in helping younger generations place more recent movements such as the Black Lives Matter Movement in context.

Walters, probably more than any other person, was an active participant in the intellectual debate, the organizational development and engagement, and the political movements and strategies of these periods. He was the go-to-guy when a journalist needed an analysis that would be understood by the public, when a black politician wanted a political strategy crafted, when a community organization wanted their issue highlighted, when a group of people wanted an organization built, or when students wanted to understand political theory and how it applied to everyday life.

Smith published We Have No Leaders: African Americans in the PostCivil Rights Era in 1996. In We Have No Leaders , Smith takes an in-depth look at the National Black Political Convention of 1972 and its aftermath, as well as at the 1984 and 1988 candidacies of Rev. Jesse Jackson for president of the United States. In this biography, Smith has expanded the body of knowledge about these events by discussing Walterss role in each. By looking at Walterss engagement in and analysis of what occurred, the reader learns about what happened at the Gary Convention and why the Black Political Assembly did not survive. It helps, for example, to understand why, with the best efforts of Walters, the Gary Convention could not realize its theme of unity without uniformity.

The reader gains an inside look at the Jesse Jackson presidential campaigns and the limitations of presidential elections in elevating the status of black people or, as Walters would term it, in the liberation of black people. Smith also discusses Walterss reflections on the limits of a black president during and after President Obamas election.

The history of university Black Studies departments is not well known beyond those who lived it. Walters had an intimate role in the development of Black Studiesbeing one of the first directors. The reader learns about disagreements concerning the direction and content of the programs that developed between professors such as Walters and some of the more radical Black Movement activists.