Teaching Palestine on an Israeli University Campus

Teaching Palestine on an Israeli University Campus

Unsettling Denial

Daphna Golan-Agnon

Photographs Jack Persekian

Translation Janine Woolfson

Anthem Press

An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company

www.anthempress.com

This edition first published in UK and USA 2021

by ANTHEM PRESS

7576 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8HA, UK

or PO Box 9779, London SW19 7ZG, UK

and

244 Madison Ave #116, New York, NY 10016, USA

Copyright Daphna Golan-Agnon 2021

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020946305

ISBN-13: 978-1-78527-501-2 (Hbk)

ISBN-10: 1-78527-501-1 (Hbk)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78527-504-3 (Pbk)

ISBN-10: 1-78527-504-6 (Pbk)

This title is also available as an e-book.

in memory

of Stanley Cohen,

a mentor and dear friend

Contents

I am grateful to all the students who shared their stories with me and allowed me to share them with you. Aaron Back, representing the Ford Foundation, lent support to the Human Rights Fellowship program. He is also a close and generous friend who encouraged me to write this book. I am thankful for the ongoing support of the Minerva Center for Human Rights at the Hebrew University, and especially grateful to the Executive Director Danny Evron. Special thanks to the wonderful research assistants: Hala Mashood, Maya Vardi and Jiries Elias. I owe gratitude to the many colleagues and friends teaching, researching, evaluating, reflecting, acting and expanding Campus-Community partnerships and to our mentor Jonah Rosenfeld who led us down this path and graciously taught us to learn from success. To Rema Hammami, many thanks for years of advising me on this book, for showing me how queer theory can be helpful when considering the legal situation of Palestinians in East Jerusalem, and for suggesting the title. The photography tour with Jack Persekian allowed me to discover new perspectives on, and from, the Mount Scopus campus where I have worked for some 30 years. I look forward to more joint trips. Thank you Janine Woolfson for a meticulous and sensitive translation, in which I can hear my own voice. Many thanks to the team of the Anthem Pressit has been a pleasure working with you.

Thank you Amotz Agnon, my lifelong partner. Thanks to my brilliant scholar-activist children Gali and Uri. I am so proud of you. It is my fervent wish that my wonderful grandchildren grow up to live in a land of peace and justice.

In the second class of the year, a student named Tal asked me, Why doesnt anybody talk about the war thats going on out there? I redirected her question to the other students. We were sitting at a round table in a classroom on the Hebrew University of Jerusalems Mount Scopus campus. The lesson hadnt begun yet and I was chopping cucumbers and helping set up the meal that one of the students had brought to share with the class. My students take turns preparing these suppers, which are always interesting and meaningful and, in most cases, delicious. Why is nobody talking about the war thats going on out there? I repeated. Is there a war? Who isnt talking about it?

The Minerva Human Rights Fellowship program in the Hebrew Universitys Faculty of Law admits outstanding students from across the universitys departments. It was November 2000, the al Aqsa intifada was beginning, but not one of the 16 students in the cohort had ever heard a lecturer mention, even in passing, the war going on out there. The students were final year undergraduates or graduate students in international relations, law, Jewish thought, education, social work, and computer science. The disturbing events taking place off campus had not been acknowledged, let alone discussed, in any of their department.

I asked the students if they wanted to talk about it.

Six of the students in the group were Palestinian citizens of Israel. Just a few weeks earlier, 13 Palestinian citizens of Israel had been killed at a rally in support of the Palestinian popular uprising in the Occupied Territories. The conversation was slow to begin and palpably cautious. Given that the students in this diverse group did not yet know one another, the round table dictated the order of discussion, with each student speaking in turn. On that day, the Palestinian students asked if they could skip their turns.

The Jewish students expressed fear and frustration. They had come to Jerusalem from various parts of the country and they felt foreign in the cold, labyrinthine halls of this hilltop campus in the heart of East Jerusalem, far from the center of town. They spoke of feeling confused and of not having a space on campus in which to process this confusion. They all expressed a desire to hear from the Palestinians. When the Palestinian students were eventually persuaded to speak, theirs was a story of twofold fear: the fear of bus bombings, which they shared with everyone, and the fear of being recognized as Arabs by other bus passengers terrified of bombings.

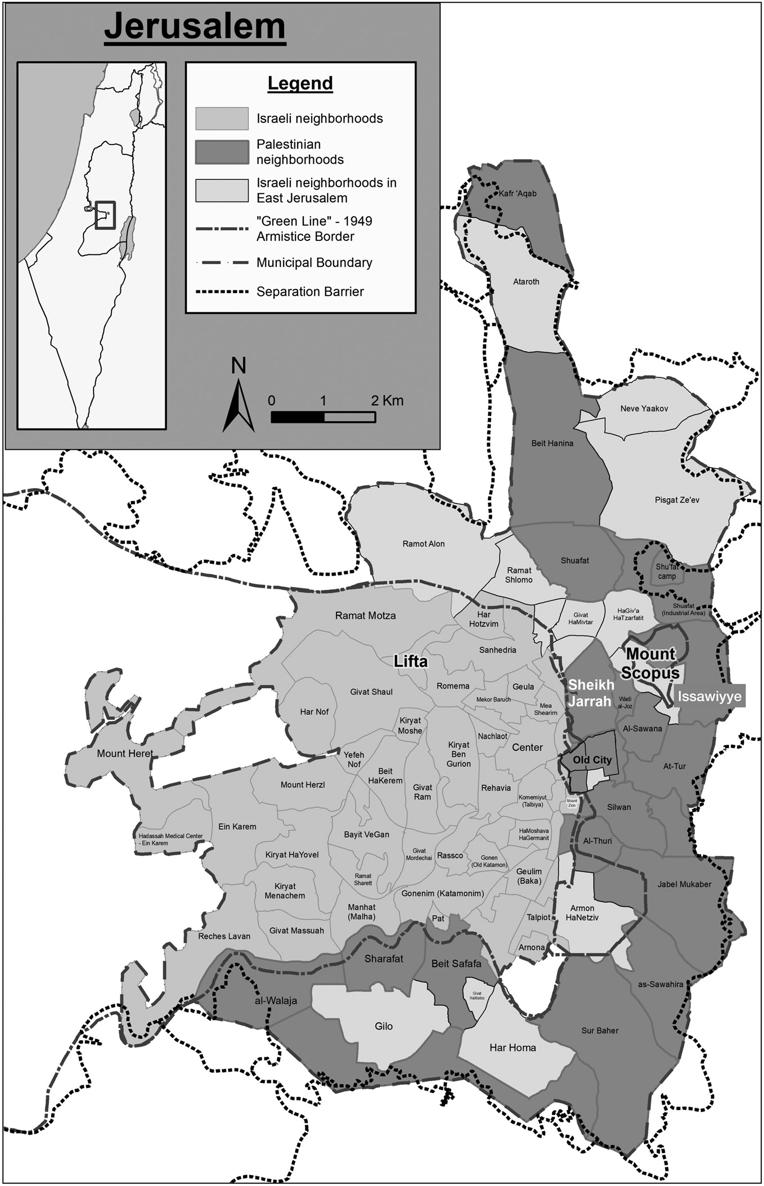

The question of why nobody discusses the war has arisen in every class since; the failure to acknowledge reality is pervasive, not unique to the Mount Scopus campus. This book will demonstrate the prevalence of political denial on all Israeli campuses. Nevertheless, the physical location of the Mount Scopus campus in the heart of Palestinian East Jerusalem makes this instance of denial particularly absurd. How on earth can reality be ignored when a student explains apologetically that she is late for class because the bus in front of the bus she was traveling on blew up, so they closed the road and I had to walk? How, when the smell of tear gas wafts into the classroom from in the nearby village of Issawiyye, can we carry on as if nothing is happening?

The campuses are political spaces and the decision not to address the war out there is as much a political statement as addressing it would be.

In spring 2017, at the behest of Education Minister Naphtali Bennet, Professor Assa Kasher published what he called an ethical code for academia, which prohibits political discourse in campus classrooms. University officials and academics condemned this violation of freedom of speech, flooding academic platforms with objections, explaining the problematic nature of every item in the code. In an op-ed published in Haaretz, I suggested that Professor Kasher should be thanked for instigating the stormy debate about freedom of expression currently taking place in Israeli academia.

Ironically, Kashers code also reinforces the BDS movements call for a boycott of Israeli academia because of its role in perpetuating the occupation. It envisions the self-censorship that already prevails on Israeli campuses being turned into an official ban. For years, Israeli academics have remained silent, for fear of saying something deemed inappropriate, and in doing so they have colluded with the disingenuous claim that the campuses are apolitical. Ministers and politicians regard the universities as leftist strongholds and endeavor to impose restraints on campus politics. As a result, the only political expressions permitted on campus at the moment are those in support of the government. In this absurd reality, inviting the Minister of Justice to speak at a graduation ceremony is not deemed a political act but mentioning the word occupation in the classroom most certainly is.