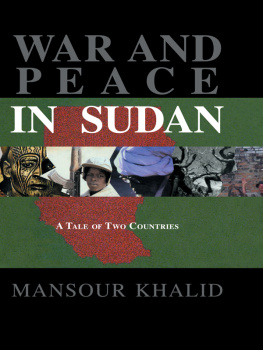

First published in 2001 by

Kegan Paul International

This edition first published in 2011 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Mansour Khalid, 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 10: 0-7103-0659-8 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-0659-3 (hbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

INTRODUCTION

How can one describe a man who all at the same time is a soldier, a political leader, a statesman, a human rights activist, a farmer and a peacemaker? A man who proclaims and demonstrates undying patriotism yet, at the same time, is an unrivalled ruthless critic of the state. Is it convincing that one who is trained to excel in military warfare could, on an even keel, be a leading advocate for peaceful solutions to violent problems?

Those are the sort of problems one faces when trying to pigeon-hole the person and character of General Olusegun Obasanjo. At first glance, Obasanjo is a labyrinth of contradictions. Jeremy Pope, a close friend of the General, while paying tribute to him, said, those who do not know him see only the contradictions. But it is only in the most refined of persons that such apparent contradictory traits of character are in essence a consistent exhibition of integrity. It is in a dimension beyond our mundane philosophy and myopic imagination that these traits intertwine to weave a pattern of human nature at its best. Once in a generation, such a character ascends through the ranks of politics in African society and affects the lives of many a people for years to come. Such notable personalities like Julius Nyerere and most recently Nelson Mandela have altered the thoughts and deeds of the societies in which they lived and bequeathed to the rest of the world a legacy of justice, freedom and human dignity.

General Obasanjo came to power, or rather catapulted into it, after the assassination of Nigeria's military ruler Murtalla Mohamed in 1976. With effortless simplicity and characteristic disdain for power, he saw his mission as that of relinquishing that power to where it belonged: the people of Nigeria. In the course of three years, he organized the peaceful transition to civilian rule resulting in the election of President Shagari. That daring act astounded many democratic-minded Africans I knew who share a common distrust for the military in politics, and a general despair of Nigerian military rulers. It even baffled me though I have had the dubious distinction of serving under a military ruler: Nimeiri. The military in many parts of post-independence Africa had behaved as if they were the nation's custodians. So Obasanjo's was not a mean achievement. The Obasanjo I know, however, is endowed with what military leaders of his ilk and many African politicians of his class do not have: a moral reserve to restrain political urges for assuming power at any cost, and an intellectual hinterland to retire to when the time has come for him to abdicate it. Oft-times, Obasanjo's advice to some of his peers who were unshakably glued to power and thinking of nothing better to do: there is life my friend beyond the State House.

Yet, contradictions are the most apparent facet of the General's character, and so too is obstinate insistence on basic values that have largely been discarded as inconvenient by many leaders. For instance, though being a career military man, he did not shy away from saying arms importation has no direct benefit, whatsoever, for African citizens. Most often than not, such arms are used to suppress and liquidate Africans within our different borders.1 He also said: The military has no business governing and if by accident they get sucked in, they should get out as soon as possible to face their traditional and constitutional duties of security and defense of territorial integrity.2 Those words fell on deaf ears in his country, where military coups continued for fifteen years with monotonous regularity.

Obasanjo's admonitions did not delight those who assumed that their right to rule is part of the natural course of history; his challenge to General Abacha's rule and the political farce that followed the annulment of the election of Basorun Abiola led to his condemnation for a life-term prison. Obasanjo's incarceration only enhanced his authority as a national leader and augmented his credentials as an apostle of democracy. A few years later, Obasanjo was vindicated by the people of Nigeria who voted him as their third democratically elected President. Yet, despite all the injustices he suffered under Abacha, Obasanjo held no grudge towards the man. In his most recent book encompassing his prison thoughts and reflections, he had this to say on Abacha: I had no bitterness or animosity against Abacha and his cohortsmy heart has no room for bitterness or animosity. Abacha has done what he did because he did not know better. Together with 14 others, the General was sentenced to death for a conspiracy against the state that did not exist. Were it not for the international and regional outcry against the sentence, the 14 would have been executed. But instead of being submerged by an appetency for revenge, Obasanjo set his mind on the essentials: building a New Nigeria where no mindless and mad Nigerian should be given the sort of opportunity that was given to

1Hope for Africa: Selected Speeches by Olusegun Obasanjo (1993). ALF Publications, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria, p. 13.

2Ibid.

Abacha. His philosophical approach to life and men is condignly reflected in the title of that book: That Animal Called Man.

I failed even after his thoughtful decision to abdicate power at will to see the depth and reach of Obasanjo's dedication until 1990 when the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars convened a symposium at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington to bring together all parties to the Sudanese conflict. Obasanjo was to chair the symposium. On the day he was to travel to Washington, his wife was killed by robbers in his Nigerian village. I knew no other man who would have done what the General did; bearing his pain and travelling to the meeting place. He only went back to nurse his grief after the symposium was concluded. That incident revealed to me an African leader I erstwhile knew not existed, one who would put aside his personal concerns, however pressing, for the public need; one who had an unwavering commitment to African causes and who would pay any price for Africa's salvation, however exacting. The people of Sudan, in the period following that symposium, became beneficiaries of these qualities of the General. He became deeply engrossed in the search for peace in Sudan, persistently working alongside other men of goodwill to bring an end to the longest war in Africa.