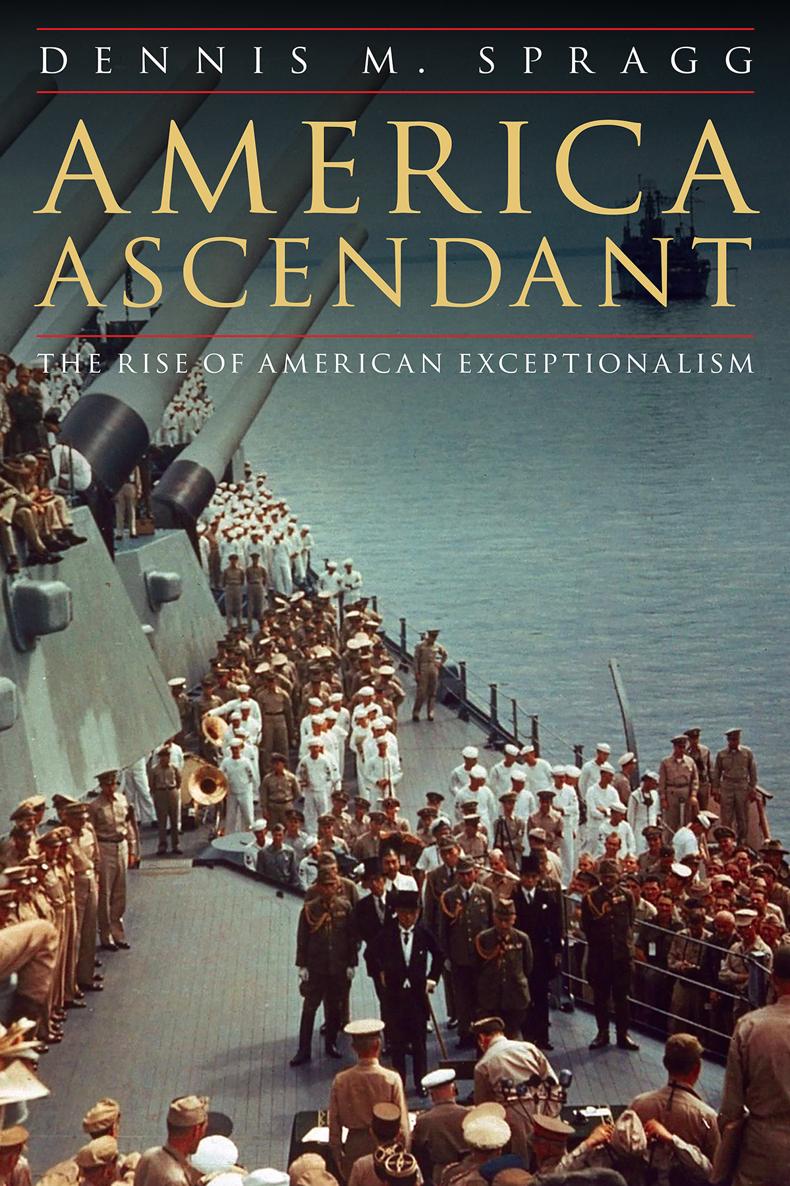

2019 by Dennis M. Spragg

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image is from the interior.

Author photo courtesy of the author.

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Spragg, Dennis M., author.

Title: America ascendant: the rise of American exceptionalism / Dennis M. Spragg.

Other titles: Rise of American exceptionalism

Description: Lincoln NE : Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019005294

ISBN 9781640121430 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781640122628 (epub)

ISBN 9781640122635 (mobi)

ISBN 9781640122642 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : World War, 19391945United StatesPropaganda. | ExceptionalismUnited StatesHistory. | World War, 1939-1945United StatesMass media and the war. | Government and the pressUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Press and politicsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Political cultureUnited

StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC D 810. P 7 U 48 2019 | DDC 940.53/73dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019005294

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

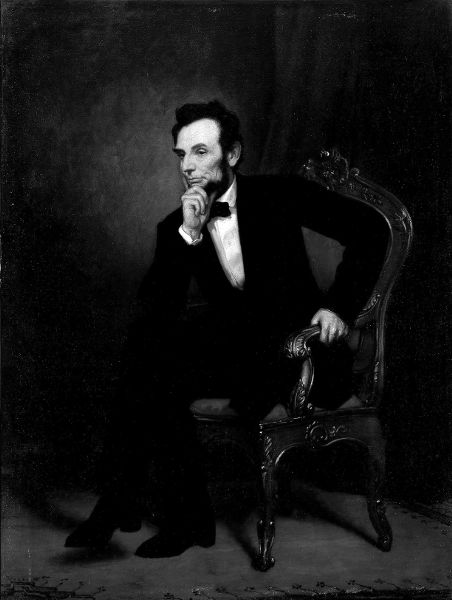

Pres. Abraham Lincoln. Portrait by George Peter Alexander Healy, 1869. White House Collection, White House Historical Association, Washington DC.

Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation. We say we are for the Union. The world will not forget that we say this. We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it. Weeven we herehold the power, and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the freehonorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail. The way is plain, peaceful, generous, justa way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud, and God must forever bless.

Pres. Abraham Lincoln, December 1, 1862

The United States of America is an exceptional nation that uniquely transcends region, race, and religion. Dictionaries define the word exceptional as (a) forming an exception: rare; (b) better than average: superior, and (c) deviating from the norm, such as having above average intelligence. Historians have used variations of all three definitions to explain how thirteen British North American colonies became an independent nation that developed into a global superpower. Attempts to define American exceptionalism differ by era, and national leaders have engaged in a robust debate over the meaning of America for most of the nations history.

Nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century political discourse was a contest between expansionism versus morality. The main themes were manifest destiny and the question of slavery. The competing ideals were well defined and widely argued; for example, Hamilton federalism versus Jeffersonian republicanism; the abolitionist North versus the slave South; and Wilsonian progressivism versus Lodge pragmatism. It took the greatest challenge in American history and skilled leadership to cause an intersection of the competing impulses to unify the nation and define American exceptionalism.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, aided by exceptional bipartisan statesmen and soldiers, changed the dynamic of competing American visions by replacing expansionism as a national imperative and replacing it with interventionism, which he defined in the Atlantic Charter as a moral responsibility. Interventionism became victory and then internationalism with the founding of the United Nations. America conceived and led far-reaching global relief, economic aid, and security arrangements that have lasted into the twenty-first century.

Two exceptional generations of Americans directed and fought World War II. An extraordinary bipartisan government alliance with industrial and media leaders, all of whom were born in the late nineteenth century, had the imagination and reason to organize and communicate on an unprecedented scale. Roosevelts Office of War Information, Hollywood, and the broadcasting industry capably defined American exceptionalism at home and abroad. Millions of exceptional Americans born in the twentieth century did not hesitate to do what was necessary to save the world. They unselfishly proved American exceptionalism on the battlefield, upholding and advancing American values.

The alliance between government and media, including the Office of War Information, Hollywood, and broadcasters, defined and communicated the convergence of national interest with moral imperative. As young Americans proved exceptionalism on battlefields in every corner of the earth, they and their fellow Americans, motivated by the ideas and ideals of their forebears and leaders communicated to them by the alliance, went on to build an enlightened postwar world.

The exceptional generations did not simply achieve victory in a global war of survival, but they did so to create a better world without the motivation of territorial conquest. What they achieved after the war and how the history of America empowered them to be exceptional is as important as their service. They need not be Americas most exceptional generations in the decades and centuries to follow. There will certainly be others who will carry the torch.

The twenty-first-century descendants of the exceptional generations have diverse and inaccurate ideas about what American exceptionalism is. Polarized political discourse has upset the equilibrium won by the wartime generations. The Vietnam War, Watergate, and the personal imperfections of self-absorbed and unorthodox politicians have clouded the memory and awareness of Americans about where they came from, why they are exceptional, what exceptionalism really is, and how they can apply exceptionalism to continue building a better nation and world. This includes the constructive role of the media and its relationship to sound governance.

The modern American media, political establishment, and special interest groups have divided themselves among red and blue states, race, gender, and lifestyle. Amazing technologies are isolating Americans rather than bringing them together. As media have fragmented among confusing options and voices, the dependable world of Walter Cronkite has devolved into a Tower of Babel. News has become commentary, as journalism has descended into partisan argument. As universities have become racially diverse but intellectually segregated as leftist bastions, false traditionalist prophets have appeared in response, preaching long-discredited doctrines of isolation and intolerance. Citizens caught in the middle yearn for a renaissance of civility and mourn the absence of civics in revisionist classrooms. Generations that have come of age during and after the pivotal Vietnam War era, devoid of civics and history, might consider the Nicomachean Ethics espoused by Aristotle, that earlier generations of conscientious Americans well understood: