Publication of this book was supported by a grant

from the L. J. and Mary C. Skaggs Folklore Fund

2011 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

p 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Burns, Sean.

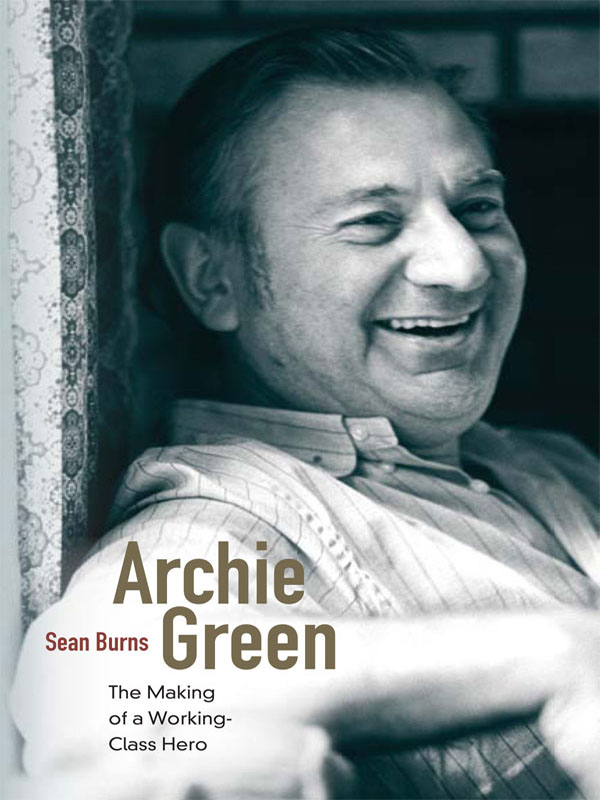

Archie Green : the making of a working-class hero / Sean Burns ; foreword by David Roediger ; with a final interview conducted by Nick Spitzer

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-07828-6 (pbk.)

1. Green, Archie. 2. FolkloristsUnited StatesBiography.

3. Working classUnited StatesFolklore. 4. Labor unionsUnited StatesFolklore. 5. FolkloreUnited States. 6. United StatesSocial life and customs. I. Title.

GR 55. G 693 B 87 2011

398.092dc23

[ B ] 2011035134

Foreword

David Roediger

My strongest memory of Archie Green has him holding on to a hug, not letting go. The occasion was an event organized to honor and study the memory of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) at University of Missouri during the 1980s. The academic talks, and a rollicking, reflective one by Archie, were punctuated by performances from the great African American socialist songwriter, poet, and singer John Handcox, who had memorialized STFU struggles in Roll the Union On and The Planter and the Sharecropper in the thirties. When the session had just ended, Archie and John found each other near the stage and embraced. Archie did not let go. The two hundred people in the audience saw something rare in U.S. culture and rarer still in academiatwo men hugging, across the color line and for a long time. Archie was right to hold on; the Missouri event turned out to be one of Handcoxs final public performances before his death in 1992.

Archie continued to hug and hold on throughout the 1990s and well into the twenty-first century. One of the highlights of the laborlore conversationsso well described in this wonderful biographythat Archie organized near the end of his life was him hugging and holding on to participants. This volume combines accounts of Greens life and times to describe the many ideas, actions, and people Archie embraced and held fast, whether from family to folk, left reformist politics to revolutionary working-class culture, craft traditions to creative breakthroughs, or individual passion to a profound desire to bring friends together in common projects.

Archie and I grew close initially and enduringly because of his penchant for holding on. We met during the 1980s when he sought me out because I was participating in cooperative efforts to preserve and revive the Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, the worlds oldest socialist publisher, which had fallen on hard times. With the biologist Stephen Jay Gould, the novelist Jack Conroy, the artist Lenora Carrington, the poet Dennis Brutus, the historian George Rawick, and the wonderful Studs Terkel and others, Archie took a leading role in our modest Friends of the Charles H. Kerr Company, part of the improbable success of holding on to and reviving the press. At Kerr, the veteran Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) editor Fred Thompson and IWW/surrealists Franklin and Penelope Rosemont shared Archies desire to maintain legends, examples, and, above all, songs of the Wobblies, as IWW members were called, and Thompson and the Rosemonts corresponded endlessly with him.

Thus when Archie visited the University of Missouri, where I was then teaching, we got together, although not without some suspicion on his part. My Kerr credentials did not fully override the fact that I was a writer, broadly speaking, within new labor history, a subfield with which Archie rightly quarreled. I, like most labor historians meeting Archie, did not know at first that I was in the presence of a legend.

We quickly became friends around two circumstances. The first involved an event marking the donation, through Green, of the amazing papers of Peter Tamony, the working-class expert on U.S. slang, to the universitys archives. The program (and to be fair, Archie) went on for a long time and became considerably behind schedule, but the moderator was still bent on following form by having several more scholars deliver formal remarks. Archie said, with no rancor but considerable firmness, that he was adjourning even if the event was not. He wanted, he added, to be outside for at least the end of a beautiful afternoon. The event ended then and there, and I, having never seen anything quite like this, followed him to watch the sunset. He opened up considerably, in part around a fear that occupational illness contracted on the waterfront left few sunsets for him to watch.

In fact, he was to live another remarkable quarter century, producing much of his most influential scholarship in very active retirement. For one of his books he interviewed me, in what proved to be the second circumstance cementing our friendship, on the origins of Wobbly as a name for IWW members. In contrast to Fred Thompson and Franklin Rosemont, whose brains he also picked, I had little to offer, coming along too late to know more than a few old Wobblies and having not yet written much on the union.

I talked not about the origin of Wobbly but about it being telling that IWW held on to the term. In contrast to the scientific socialism of the sectarian left that superseded the IWW, the working-class radicals of the singingest union in the United States reveled in the wobbles of the world and of themselves. Archie brightened greatly and republished the interview in his essay on Wobbly. I had spoken to his, and our, passion for holding on to a politics suspicious of modernist straight linesto his commitment to what Burns aptly discusses as cultural pluralism and more.

That love of multiplicity created contradictions that Archie characteristically and stylishly embraced. His concept of laborlore prioritized working lives insistently. When a large history conference convened in San Francisco during the 1990s, Archie celebrated his return to health after a series of set-backs by convening a tour of labor sites and walked a half-dozen eager invitees into the ground. We lingered forever at first in one small area as Archie stopped in every building, emphasizing that all were labor sites built by workers and every one deserved a marker detailing all who built it. When we moved on, it was to the marvelous Mechanics Institute, a monument to a world beyond work and by then, much to Archies delight, a chess center.

The same ability to see working-class experiences in the round, without minimizing the critical dimension of labor under capitalism, had Archie often eagerly asking me what would happen if workers were requested to name their roles and identities, and given no cues about the response. He predicted that identities such as born-again Christian, guitar player, Giants fan, Filipina, Catholic, and lesbian would very often come before worker or union member on resulting lists. The lesson was to deepen, not abandon, working-class studies.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.