STUART A. WRIGHT is associate professor of sociology at Lamar University in Texas.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1995 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1995

Printed in the United States of America

04 03 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN: 0-226-90844-5 (cloth)

0-226-90845-3 (paper)

ISBN: 978-0-226-22970-6 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

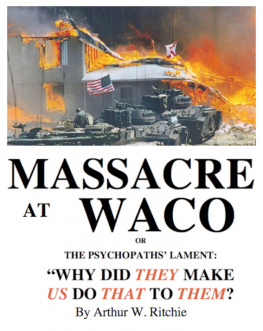

Armageddon in Waco: critical perspectives on the Branch Davidian conflict/edited by Stuart A. Wright.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Branch Davidians. 2. Waco Branch Davidian Disaster, Tex., 1993. 3. Psychology, Religious. 4. CultsUnited StatesPsychology. 5. United StatesReligion1960 6. Psychology and religion. I. Wright, Stuart A.

BP605.B72A76 1995

299'.93dc20

95-8872

CIP

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements or the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48 1984.

Preface

As this manuscript entered the first stages of production in December, the Treasury Department announced the reinstatement of two BATF agents previously dismissed for their roles in the Waco Branch Davidian fiasco. The records of Phil Chojnacki, special agent in charge of the Bureaus Houston division who supervised the raid, and Charles Sarabyn, assistant special agent in the Houston division, were expunged and each was reassignedwith full back pay and benefitsaccording to settlements negotiated by attorneys for the BATF and the agents (Houston Chronicle, December 22, 1994). The actions by the Treasury Department were both disturbing and perplexing given that the departments own report castigated the two agents for proceeding with the raid despite specific instructions from their superior (Ron Noble) to abort if the element of surprise was lost. Setting aside legal and ethical questions about the defensibility of the planned raid, the Treasury Department report states unequivocally that agent Robert Rodriguez, who covertly joined the sect as part of an intelligence gathering operation, warned agent Sarabyn through an intermediary that the raid had been compromised only minutes before the command was given to commence. Curiously, Sarabyns reaction was to accelerate, rather than abandon, the raid. Later, the report indicates that agents Chojnacki and Sarabyn lied about Rodriguezs disclosure and attempted to conceal their own misjudgments about the entire episode.

While some critics observed that the actions of these government agents were deserving of criminal charges, Treasury moved quickly to quell public criticism by initiating a disciplinary review culminating in dismissal. BATF Deputy Director Daniel Black concluded in October that the agents (1) made gross errors in judgment (read: should never have carried through with the assault), (2) issued false and misleading statements to authorities, and (3) in Chojnackis case, attempted to shift blame to subordinates. Yet, in the end, two federal officials whose errors are linked directly to the deaths of six people in the initial assault (and indirectly to the deaths of seventy-four people in the April 19 fire), walked away with their jobs intact, their incomes and benefits secured, and their legal fees paid by BATF. By any measure, the most recent decisions by this federal agency add another puzzling chapter to the debacle at Waco.

This turn of events provides evidence for two predominant themes of the book: first, that marginal religions and their members are accorded diminished human and social value, largely tied to disparaging stigmas and widespread stereotypes (brainwashed cultists) that recall some of the most vicious racial, ethnic, and religious prejudices of our nations past; and second, that minority religions are more likely to be victimized by extreme efforts of social control, most notably by government, but hastened and incited by selected interest groups. These themes help to explain the seemingly inexplicable attitude of callous expendability shown toward the Branch Davidians, demonstrated by BATF officials who orchestrated the raid, as well as the calculated, noose tightening strategies of the FBI during the standoff that escalated the conflict, and the tepid response of federal authorities to the various excesses and face-saving machinations of their own personnel.

The Branch Davidian melee is a tragic page in history and clearly deserves close scrutiny on its own merits. The congressional investigation called for by civil and religious rights groups may yet materialize; however such an effort may also be rendered impotent by special interests or partisan politics. All the more reason that the events at Mt. Carmel not be pushed aside, but instead dutifully exhumed, carefully recorded, and frankly analyzed for public consumption, disentangled from self-serving political agendas, official deceit, and government secrecy in the conveniently redacted reports, particularly the one issued by the Justice Department. Pulitzer prize winning columnist William Safire echoed the sentiments of many informed observers when he referred to the Justice report as a whitewash (Houston Chronicle, October 16, 1993). Special investigator Edward Denniss conclusion that there was no place in the evaluation for blame blatantly contradicts the accompanying reports of social and behavioral science experts Ammerman, Sullivan, Cancro, and Stone, whose evaluations of FBI actions were damning. In effect, Ammerman and colleagues suggested that federal agents were largely responsible for the explosive outcome at the Davidian settlement.

At the same time, while a case for the culpability of law enforcement can be made in the Waco affair, an explanation of the problem cannot be reduced simply to government malfeasance. Clearly other social actorsboth collective and individualplayed significant roles. It is precisely this larger configuration of social forces that needs to be addressed. In this regard, Waco has much broader implications. There is substantial hostility directed toward new or unconventional religions, built on unsupported fears, perpetuated by misguided or reactionary interests, and quietly but thoroughly woven into the very fabric of society. Against this backdrop of peculiar weave, the debacle at Waco was made possible, perhaps probable.

Through this collective work, it is our hope that readers will discover both the particular and the general, a critical link between the ostensibly isolated case of the Branch Davidians and the larger cultural ethos of antagonism surrounding sectarian religious expression. Sociologically, these two variables are inseparable. The Mt. Carmel events were as predictable as they were avoidable. But one suspects that other Wacos may lie ahead if we fail to understand the forces that shaped and ignited the violent confrontation between sect and state.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements or the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48 1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements or the American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48 1984.