First published 1986 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2008 by Taylor & Francis.

Preface to the Expanded Edition 1994 by James D. Wright.

Copyright 1986 by James D. Wright and Peter H. Rossi.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2007046172

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

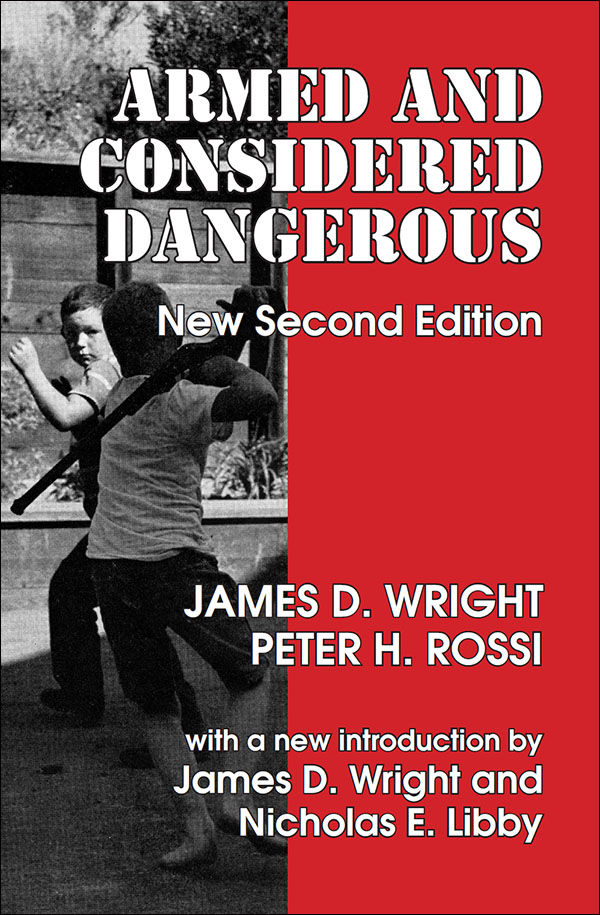

Wright, James D.

Armed and considered dangerous / James D. Wright and Peter H. Rossi;

with a new introduction by James D. Wright and Nicholas E. Libby.

New 2nd ed.

p. cm.

A reissue of the 1994 ed., with a new introduction.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-202-36242-7

1. Gun control--United States. 2. Firearms and crime--United States. I. Rossi, Peter H. (Peter Henry), 1921-2006. II. Title.

HV7436.W75 2008

363.4'50973--dc22

2007046172

ISBN 13: 978-0-202-36242-7 (pbk)

Armed and Considered Dangerous was originally published in 1986. Now a bit long in the tooth, the book is still regularly cited in scholarly, popular, and public policy discussions of guns and what to do about them. It was and (we believe) remains the most ambitious survey ever undertaken of the criminal acquisition, possession, and use of guns. Several of the findings have become coin of the realm in the gun control debate, cited frequently by persons who have long since forgotten where they came from or what their limitations are. Several other findings, including many that we regard as important, have been largely ignored. Still other findings have been superseded by better and more recent data or rendered anachronistic by intervening events.

Without doubt, the United States is among the most heavily armed private populations on earth. Half of all US households own at least one gun, and there are something on the order of 200 million firearms in circulation. As every student of comparative crime and homicide rates knows, we are also among the worlds leaders in criminal violence. Whether these facts are causally related is hotly debated. To many, it seems obvious that rates of private gun ownership and rates of violence must be connected, but this apparently obvious connection has proven exceptionally difficult to document. Armed and Considered Dangerous began with the assumption that if there is an important connection here, it would necessarily have something to do with where, how, and why criminals obtain, carry and use guns.

Guns are involved in an enormous number of crimes in this country, hundreds of thousands of them annually; the number of times that guns are used to threaten, intimidate or harass people is uncounted but certainly large. In other countries with stricter gun laws and fewer privately possessed firearms, gun crime is rare. It is thus an easy conclusion that if we had fewer guns and stricter gun laws, we would also have less crime, violence, and intimidation. This is also the conclusion of scholars such as Anderson (1985), Zimring and Hawkins (1987), and many others. On the other hand, we know that most privately owned firearms are owned primarily for socially innocuous sport and recreational purposes such as hunting, target shooting, collecting, and the like, and we also know that many privately owned firearms are used in self-defense against crime, perhaps as often as a million times a year or more (Kleck, 1988a). Most of the 200 million or so guns in private possession in the US, in short, seem to have nothing to do with the crime and violence issue one way or the other; among the remainder, it is a plausible surmise that they are used as often to deter crime as to perpetrate it. Connections that seem obvious on the surface sometimes dissolve under closer scrutiny; detailed and systematic examinations of the evidence concerning guns, crime, and violence in the United States have called the obvious connections into some doubt (e.g., Wright, Rossi, and Daly, 1983; Kleck, 1991).

Our research program on guns and violence now spans nearly two decades and like everyone else who works in this area, we are regularly asked whether gun control is not the answer. The question fails in the first instance to recognize that gun control is an exceedingly nebulous concept. To say that one favors gun control, or opposes it, is to speak in ambiguities. In the present-day American political context, stricter gun control can mean anything from Federal registration of firearms to mandatory sentences for gun use in crime to outright bans on the manufacture, sale, or possession of certain types of firearms. One can control the manufacturers of firearms, the wholesalers, the retailers, or the purchasers; one can control the firearms themselves, or the ammunition they require, or the uses to which they are put. And one can likewise control their purchase, their carrying, or their mere possession. Gun control thus covers a very wide range of specific interventions. No thinking person could unilaterally favor or oppose everything that falls within that range.

Our first major gun study was a comprehensive and critical review of the extant literature on guns, crime, and violence (Wright, Rossi, and Daly, 1983). In doing that research, we learned that there are approximately 20,000 gun laws of various sorts already on the books in the United States. A few of these are Federal laws (such as the Gun Control Act of 1968), but most are state and local regulations. It is a misstatement to say, as pro-gun-control advocates sometimes do, that the United States has no meaningful gun control legislation. The problem, if indeed there is one, is not that laws do not exist but that the regulations in force vary enormously from one place to the next, or, in some cases, that the laws being carried on the books are not or cannot be enforced.

Much of the gun legislation now in force, whether enacted by Federal, state, or local statutes, falls into the category of reasonable social precaution, being neither more nor less stringent than measures taken to safeguard against abuses of other potentially life-threatening products, such as automobiles. It seems reasonable, for example, that people should be required to obtain a permit to carry a concealed weapon, as they are virtually everywhere in the United States. It is likewise reasonable that people not be allowed to own automatic weapons without special permission, and that felons, drug addicts, and other sociopaths be prevented from legally acquiring guns. Both these restrictions are in force everywhere in the United States, because they are elements of Federal law. Nearly all people, even hard-core gun nuts, favor these sorts of obvious and reasonable precautions and related precautionary measures in the same vein.