We gratefully acknowledge permission to reprint portions of this work from JAI Press, Humanity and Society, The Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, The Journal of Religion and Health, and Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Service.

First published in 1993 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1993 Taylor and Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kayal, Philip M., 1943-

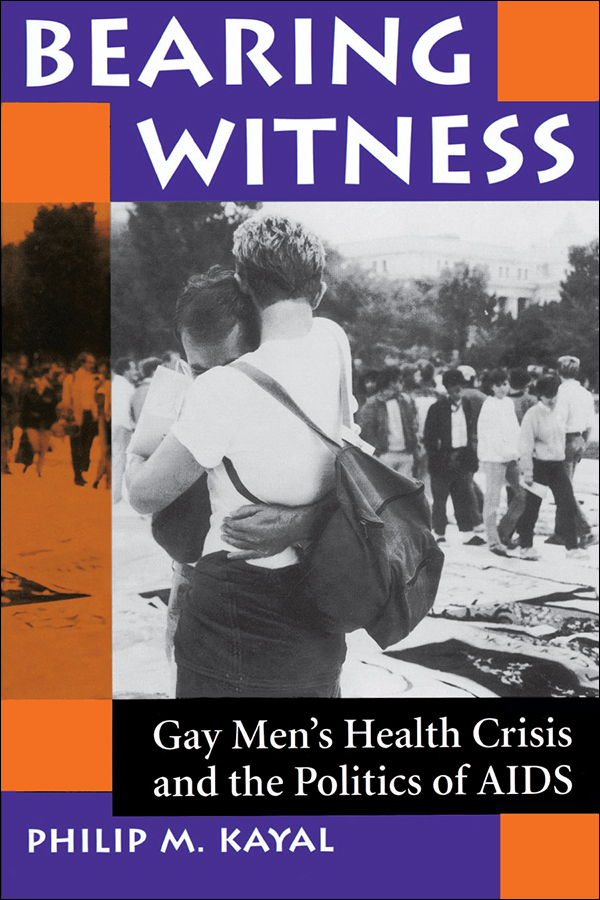

Bearing witness : Gay Mens Health Crisis and the politics of AIDS

Philip M. Kayal.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8133-1728-2.ISBN 0-8133-1729-0 (pbk.)

1. Gay Mens Health Crisis, Inc. 2. Gay menNew York (N.Y.)Social conditions. 3. Gay menNew York (N.Y.)Attitudes. 4. Volunteer workers in community health servicesNew York (N.Y.) 5. Gay menUnited StatesPublic opinion. 6. Public opinionUnited States. 7. HomophobiaUnited States. 8. AIDS phobiaUnited States. 9. AIDS (Disease)Political aspectsUnited States. I. Title.

HQ76.2.U5K39 1993

305.389664dc2092-40293

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-1729-8 (pbk)

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED to past friends who have died of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and to present and future friends who struggle daily with gross illness in both their personal lives and community. To Diego Lopez, the creator and initiator of client services at Gay Mens Health Crisis (GMHC); to Michael Doyle, a dedicated sociologist and volunteer who was just beginning his career as a psychoanalyst when he fell ill with pneumocystis; to Horatio Benegas and Victor Bender, who lived and died proudly as gay people by taking care of each other and who intimately and directly introduced me to the process of dying; to Howard Goodkin, a dear friend who was diagnosed with AIDS just as he was beginning to edit this manuscript; to theologian Kevin Gordon, whose brilliant use of systematic theology to undermine Catholic arguments about homosexual legitimacy was cut short by AIDS; to Jerry Norman, a wonderful opera singer who died not long after his final moving recital at Cooper Union; to his lover, my beloved friend Leonard Barton, who introduced me to high art and culture, and in whose loving arms Jerry died; to Dan Bailey, first official hotline director at GMHC and my longtime friend and confidant; and to Dr. Paul Jerro, a friend and cousin, who chose to burden no one with his illness, keeping it to himself until the very end. Like all the others, he was a good, generous, honest, and kind person.

They were all in their late thirties and early forties and had led honorable lives when their AIDS diagnoses were made, often only weeks or months apart. As friends, our loyalty never wavered. Over time, we pulled even closer together. Though the heavens fell on us, we made ourselves available to one another and to dozens more.

Then there were Terry and Chris, lovers who came out to each other and stayed together for life. They were among my closest friends, parts of myself. They taught me a lot, offering a different perspective because they were not trained, official AIDS volunteers, preferring to informally help their sick friends by themselves. And help they did, perhaps a dozen or so friends.

They had built a cabin in a gay campground near Scranton, Pennsylvania, and took it upon themselves to provide safer-sex education for their camping buddies who lacked access to gay or AIDS news. They were both diagnosed in November 1989 after the three of us took the AIDS test. Having been with me on this project from the very beginning, Terry died the day this book was finished, entrusting Chris to us, his friends. Less than a year before, Chriss only brother had died of AIDS.

Like most people living with AIDS, those I have known who have died from its ravages led rewarding lives, always giving of themselves as generously as they could. Each had his own personality and died as he lived, in ways that were unique and special. For no particular reason, some died quickly and quietly while others struggled and lived on for years. Most died true to themselves and with a public acknowledgment of who they were, how they had lived, and why they died.

For the most part, my friends left in peace, free of shame and guilt, and with their business on earth completed. Unexpectedly, their lives and deaths became signs of hope and symbols of love and service. Their deaths have taught ustheir many carepartners and friendshow to live joyfully and mourn unabashedly. Though often ill and grieving themselves, they helped us come together as a family. Our dying friends gave us, the living, the opportunity to do good, to discover our fears and limitations and our capacity to absorb suffering.

Perhaps they are the lucky ones because they do not have to face AIDS and the world alone. Today, we survivors have little to be joyful about. In a friendless world, whats the point of being the last of a generation to live, perhaps even to die?

Generally, the people that I mourned were all surrounded by love. As friends and families, we shared their enormous suffering and pain, their endless loneliness and fear. For many of us, those living with AIDS appear heroic and their anguish seems profound.

AIDS shatters everyones hopes and dreams; its unpredictability and its inconsistencies are monumental. Not knowing how, or who, or when, or why him or her and not me or them is a harrowing experience. Looking for an answer or the answer becomes a journey inward to the depths of the soul. For this reason, AIDS remains a primary mystery in the human journey toward selfdiscovery.

Because AIDS affects so many people in one way or another, it simultaneously produces both anger and the need to forgiveto be reconciled to ourselves as individuals and as part of a community. It makes one want to run awayto be detached from the world.

Nothing really matters during or after AIDS. Yet, for all the deaths to be remembered and understood, the meaning of AIDS in human terms needs to be made known, if not highlighted.

It is for this reason that this book is also dedicated to all those who witness the suffering of AIDS, in particular to the families, friends, and carepartner volunteers at Gay Mens Health Crisis, who are forced as much by circumstances as by choice to daily take up the cross of caring in ways that bring peace and respite instead of despair.