This book was published with the assistance of the Z. Smith Reynolds Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2021 Warren Eugene Milteer Jr.

All rights reserved

Designed by Richard Hendel

Set in Miller, Sentinal and Egiziano by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

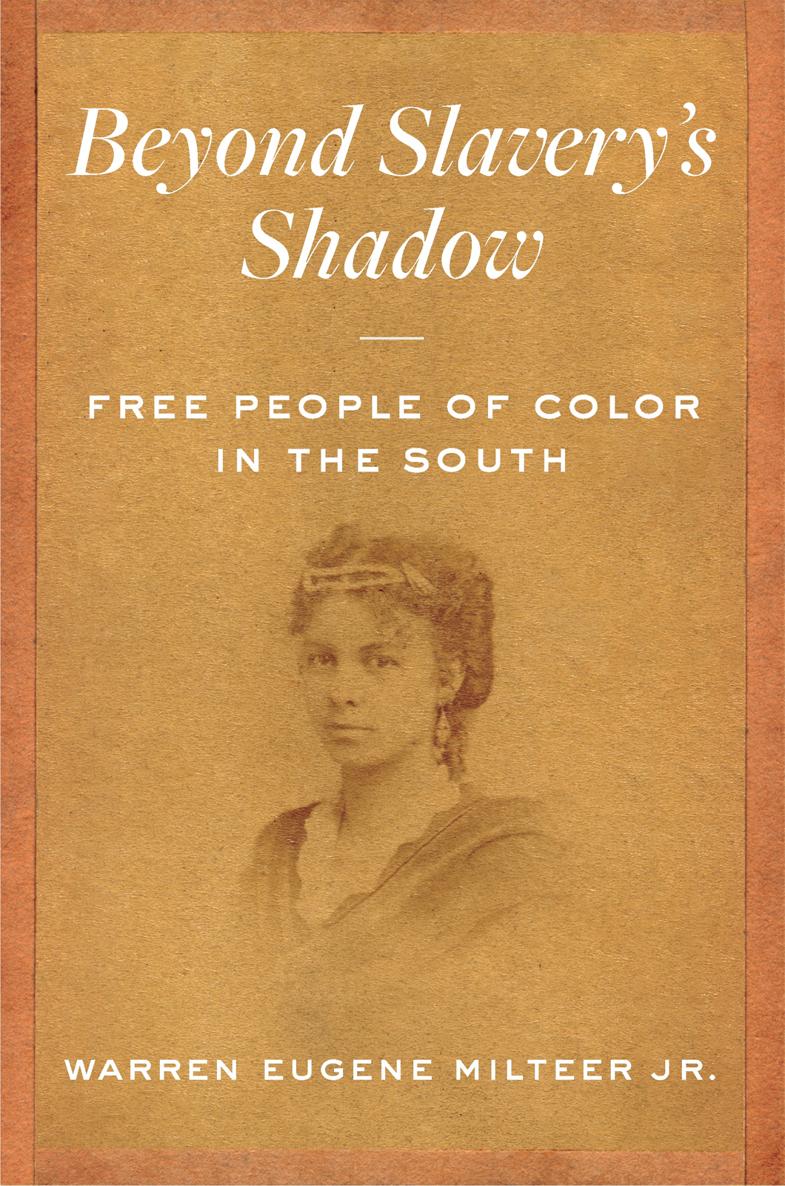

Cover photograph: Theodosia A. Lyons, a free person of color, was born in South Carolina but later relocated with her family to Ohio. Photograph courtesy of Warren Eugene Milteer Jr.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Milteer, Warren E., Jr., author.

Title: Beyond slaverys shadow : free people of color in the South / Warren Eugene Milteer Jr.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021003644 | ISBN 9781469664385 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469664392 (paperback) | ISBN 9781469664408 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Free African AmericansSouthern StatesHistory. | Free African AmericansSouthern StatesSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC E185.18 .M55 2021 | DDC 975/.00496073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021003644

INTRODUCTION

Over the course of nearly eighty years, Amariah Read lived out a life that was typical of many men of his generation in the South. Born a subject of the British crown around 1762 in Nansemond County, Virginia, by age sixteen, Read had enlisted in the effort to overthrow British power in Virginia and several other colonies. After participating in various skirmishes against British forces, Read was present for the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown. Following the war, Read returned to Nansemond County, settling down on an eighty-acre tract with his growing family by the early 1800s. Reads eighty acres eventually became the inheritance of his children, who would continue to prosper from the foundations laid by their father.

Yet Amariah Read also stood apart as a man who was born free in a time when most other people of color in the future U.S. South were born enslaved. Unlike the majority of people termed colored in his community, Read could and did hold title to personal and real property. He could work for himself, provide for his family, and keep his wages without interference from a white master. In the courts of Virginia, he could sue and be sued. As a free person of color, however, he was also subjected to an increasing number of restrictions and forms of legal discrimination. Since the time of his birth, Virginia law prevented him from enjoying some of the civil rights possessed by his white male neighbors, including the right to vote and the ability to hold public office. When Read decided to spend the rest of his life with Betsey Skeeter, Virginia law prohibited them from marrying because he was colored and she was white. By the time of his death, the state had passed laws that prohibited Read from traveling freely between Virginia and other localities, required him to obtain a license in order to own a gun, and demanded that he register with county officials in order to receive documents proving his free status. Read was wedged in the precarious position of being both free and yet a person of color.

The complexity of Reads experiences reveals some of the social intricacies of life in the South from the colonial period through much of the nineteenth century. The social order of the South stood on a platform steadied by an assortment of intersecting social hierarchies that made Read and other free people of color both privileged and victimized, both celebrated and despised. During the earliest days of colonization, many of those who traveled from Europe and established themselves in North America had decided that the individuals they termed negroes, mulattoes, mustees, and Indianspeople of colorwere inherently unequal to the mass of people they categorized collectively as white. This viewpoint vindicated the denigration, enslavement, and genocide of the indigenous people of the Americas as well as provided justification for the capture and commodification of thousands of people with connections to various parts of Africa who arrived in American ports as enslaved laborers. Yet the racial hierarchy was not the only form of hierarchy helping to uphold the social order. Hierarchies based on wealth, gender, occupation, reputation, and religion coexisted with ideas promoting white supremacy and discrimination against people of color. And at no time did the hierarchical relation between legal freedom and enslavement dissipate from southern society. In so many ways, southerners expressed the constant importance of distinguishing who was free and who was enslaved, even when those people were not classified as white.

The intersection between different forms of hierarchy ultimately led to the political and social inconsistency that characterized the South from the early days of European colonization through the Civil War years. Under the laws of Virginia, Amariah Read could sue a white man but could not testify against him in court. Although he could not marry Betsey Skeeter because Virginia law prohibited unions between persons of color and whites, law enforcement in his community allowed Read to live with Skeeter in the same house. At least some of his white neighbors recognized Betsey as his wife, even when the law would not. These inconsistencies were not exceptions in the South but standard throughout the region.

Appearing in the colonial period, the theory of white superiority and proslavery ideology slowly poisoned the social and political environments in which free people of color experienced their daily lives. These ideas were part of the intellectual technology that gradually reshaped the South from Native ground to scenes of unprecedented levels of exploitation and expropriation. Over time, southern politicians found attacking free people of color and their liberties to be an expedient way to promote these ideas and uphold the projects of extraction and enslavement attached to them. During the colonial period, the politicization of free people of color in an effort to defend human bondage and land exploitation was constricted. In communities where various forms of hierarchy were well accepted and abstract discussions of freedom were infrequent, strong advocacy for proslavery and white supremacist stances were of limited necessity.