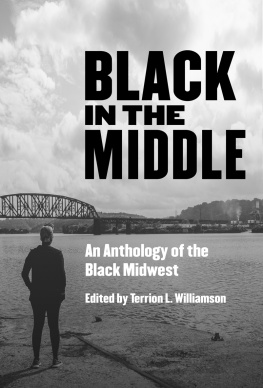

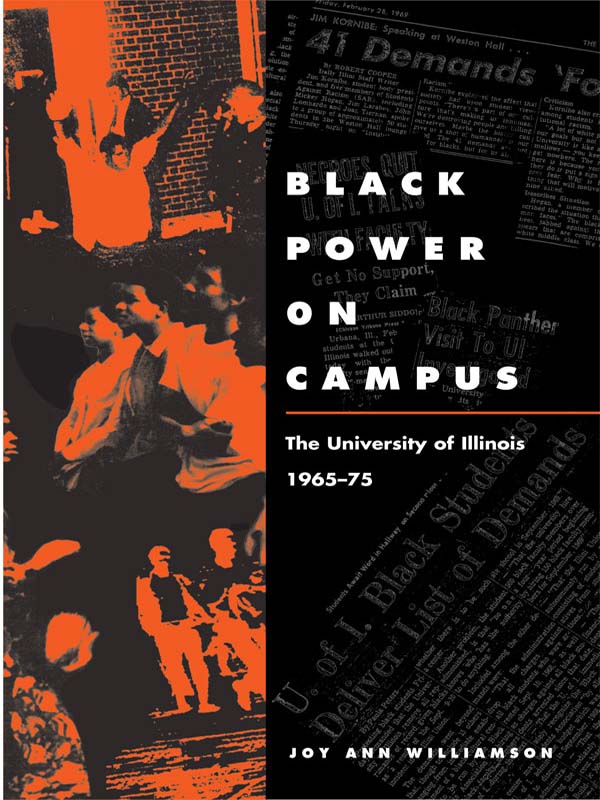

BLACK POWER ON CAMPUS

JOY ANN WILLIAMSON

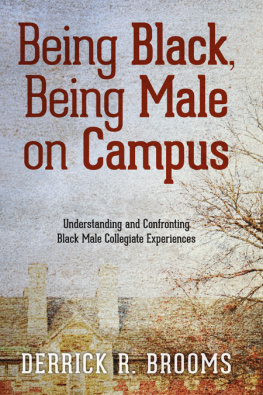

Black Power on Campus

______________________

THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS, 196575

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

URBANA AND CHICAGO

2003 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

C 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Williamson, Joy Ann.

Black power on campus : the University of Illinois, 196575 / Joy Ann Williamson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-252-02829-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. University of Illinois at Urbana-ChampaignHistory20th century. 2. African American college studentsIllinoisPolitical activity. 3. Discrimination in higher educationIllinois. 4. African AmericansCivil rights. I. Title.

LD2380.W55 2003

378.773'66dc21 2002015832

To my ever-loving family

and

to Black Illinois students

before me who paved the way

________________________________________________

What is happening in the United States is one facet of the world-wide revolution of rising expectations. Colonialism is dead. White supremacy is dying. Governmentally imposed segregation will be abolished in the United States eventually. There is no stopping place between the granting of a few rights and full citizenship. Once the first Negro was educated, once slavery was abolished, America made her choice. Negroes will demand and secure the same rights as other citizens. No other Americans have asked for more than this, or settled long for less.

Jack Peltason, University of Illinois faculty member and future chancellor, 1961

Contents

__________________________________________________________

Acknowledgments

____________________________________________________

This book has not been an individual endeavor. Several colleagues and friends contributed to it and sustained me through the writing process. James Anderson, Anthony Antonio, Ronald Butchart, Larry Cuban, and David Tyack read various chapters at different stages. They were very generous with their time, and their expertise greatly improved the manuscript. James Anderson, in particular, has always made room in his busy schedule to read various drafts and offer advice on any and every part of the manuscript. I cannot express how grateful I am to him. Also, the archivists at the University of Illinois, including Bill Maher, Chris Prom, Ellen Swain, and Bob Chapel, made the arduous task of combing through materials a much easier process than it could have been. Their knowledge of archival holdings at the university was invaluable. Jane Mohrazs editing substantially improved this book. In every writing venture my family has provided support, emotional and otherwise. My parents, Willard and Donna Williamson, and my sister, Julie, continually check in to make sure I am on track and offer support regardless. Rod Sias has been a close confidant and constant source of strength.

A postdoctoral fellowship from the National Academy of Education and the Spencer Foundation allowed me the time to concentrate on the work and finish it in a timely fashion. Generous support from Stanford University also helped bring this book to fruition.

Parts of the introduction and White Colleges and Universities, which appeared in the Journal of Negro Education 68, no. 1 (Winter 1999): 92105.

This project would not have become a reality were it not for my interviewees, who showed an interest in the project, graciously opened their homes and memories, and continue to support my career. I believe I am part of their legacy and consider this book an attempt to give back to those who helped make Illinois a more diverse, hospitable, and academically rewarding campus.

In particular, I am indebted to Clarence Shelley, the first director of the Special Educational Opportunities Program and now associate vice chancellor emeritus. I am only one of many students who has benefited from his presence at Illinois. His retirement from Illinois ended over thirty years of service to Black students in particular and the university in general. He will be missed.

Abbreviations

_________________________________________________________________________

| BSA | Black Students Association |

| CORE | Congress of Racial Equality |

| EOG | Equal Opportunity Grant |

| ISR | Illinois Street Residence Hall |

| NAACP | National Association for the Advancement of Colored People |

| SEOP | Special Educational Opportunities Program |

| SNCC | Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee |

Introduction

___________________________________________________________________

The history of Black students at predominantly white colleges and universities is a complicated one of discrimination, racism, protest, and resilience. Their experience, mode of resistance, and focal point for protest shifted over time and closely mirrored the ebb and flow of the Black freedom struggle in the United States. An unwavering belief in the importance of education made schools, including postsecondary institutions, an important battleground for Black liberation efforts. Black students became the battering rams and in many ways the vanguard of the struggle for equal education. From the late 1960s through the early 1970s, in particular, Black college students not only participated in societal reform but also determined the path of it. During the Black Power era, Black youths became the ideological leaders of the Black struggle. They helped redefine the goals and tactics of the struggle and demanded change in American institutions, including their college campuses.

This book examines the role of Black students at one institution, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Its purpose is twofold. First, it is a comment on how social movements influence institutions of higher education. Black students, bolstered by Black Power, demanded fundamental changes to campus curricula, policies, and structure. They took Black Power principles and molded them to fit their specific context: Black students attending a predominantly white university. Second, it is a comment on the nature of higher educational reform during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It analyzes the interaction between students and administrators and how their relationship shaped higher education. The text provides an examination of institutional responsiveness to particular clientele, an understanding of how agents within an institution precipitate reform, and an analysis of one of the benchmarks in American educational history.

Some scholarship on the educational reforms of the 1960s employs a top-down perspective. This top-down perspective not only identifies legislative mandates and administrator-initiated policy shifts as the most important historical markers but also assumes a national consensus on the worth of ethnic studies programs, cultural centers, and other race-based campus initiatives. The complexity of the historical process is lost with this type of analysis. Top-down interpretations minimize the alienation Black students experienced at predominantly white institutions, ignore the daily struggles of Black students to maintain psychological and academic well-being, and disregard the fact that Black students chose to participate in the Black student movement despite pressure to the contrary from parents, administrators, and other sources. Of course federal initiatives and liberal administrators and faculty played a role in institutional change, but the role of Black students and their belief in Black Power principles should not be minimized. Even though most campuses had only a few Black activists, these students fought institutionalized racism on campus with Black Power ideology, carved a niche for themselves in the Black liberation struggle, and were at the center of higher education reform.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.