Published by Otago University Press

PO Box 56 / Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

F: 64 3 479 8385

E:

W: www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2012

ISBN 978-1-877578-18-2 (print)

ISBN 978-1-927322-05-5 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-927322-06-2 (mobi)

Copyright Karen Nairn, Jane Higgins and Judith Sligo 2012

Images copyright their individual creators

(anonymised via codenames) as credited 2012

Publisher: Wendy Harrex

Editor: Georgina McWhirter

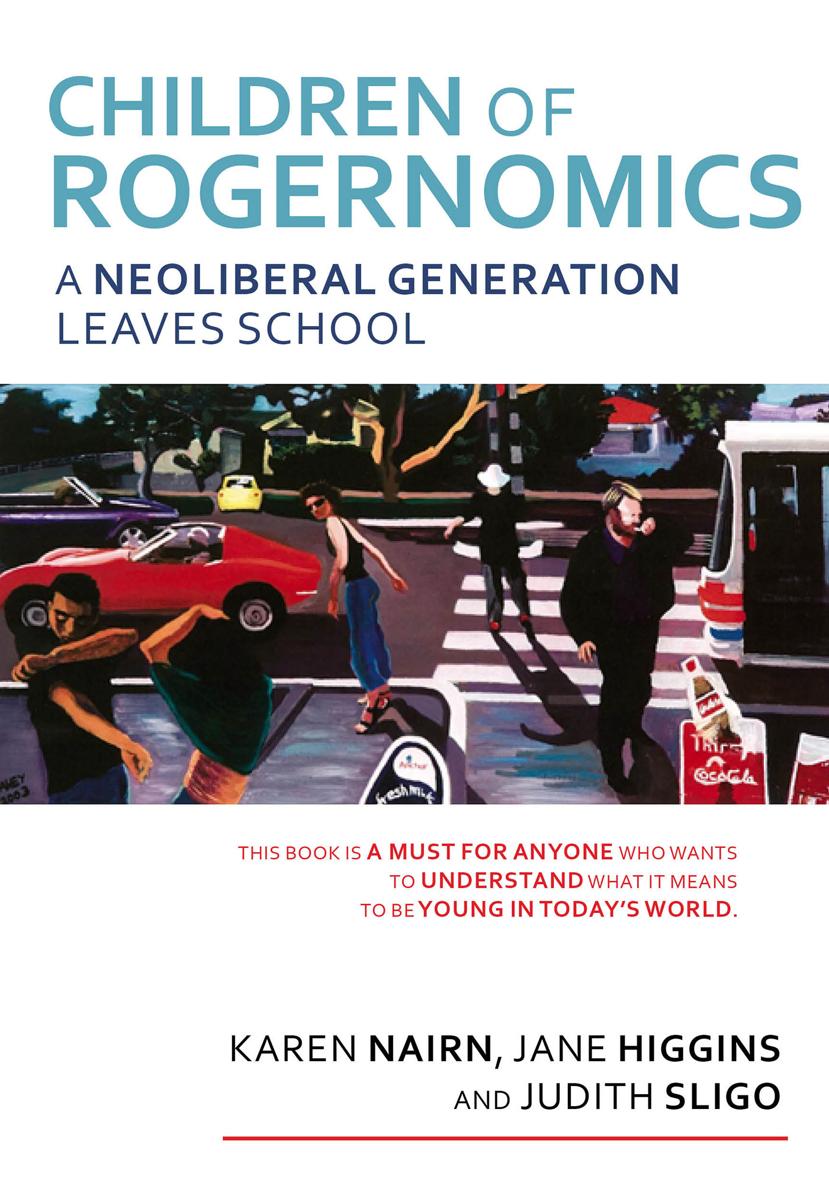

Cover design: Fiona Moffat

Cover image: 'At the Crossing' (2003), Jacqueline Fahey

Typeset by Otago University Press

Ebook conversion 2015 by meBooks

FOREWORD

This book lives up to the promise of its title. Karen Nairn, Jane Higgins and Judith Sligo provide an in-depth and compelling account of the impact of New Zealands neoliberal policies on the generation of young people born in the years immediately following 1984. It exposes, in young peoples words, stories that are authentic and hard-hitting.

Neoliberal ideologies have distinctively framed these young peoples lives. The authors draw on innovative research practices to reveal how young people themselves work and re-work the possibilities, opportunities and constraints of their times. Their analysis brings to life young peoples use of the material and cultural resources available to them, including public narratives concerned with transitions, youth, gender, ethnicity and social class, as well as local knowledge, family and friends.

Children of Rogernomics also provides a unique insight into the ways in which identities are crafted in relationships with significant others. It reveals the impact of discourses of neoliberalism that both obscure the structural basis of inequalities and insist that failure to achieve standard transitions is the result of personal inadequacy. It shows how institutions drawing on deficit discourses about young people create additional barriers for those who are other often young Pasifika and Mori, and young working-class women and men. Nairn, Higgins and Sligo bring the language, lives, places and hopes of these young people into focus, showing how ordinary lives can be inspirational.

This book is a must for anyone who is interested to understand what it means to be a young person in contemporary times.

Johanna Wyn

Director, Youth Research Centre

Professor of Education, The University of Melbourne

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our heartfelt thanks go to our ninety-three participants first and foremost. Your willingness to talk about your lives during your last year of high school and again a year later is a gift, and this book, a way to share your gift. We have tried to do justice to the richness of your lives.

We would also like to acknowledge our thirteen peer researchers, who participated in our research and interviewed two peers each. Your research expanded our participant group and we are grateful for your work.

Thank you to our other researchers whose research and commitment made the project and ultimately this book possible: Brigid Frayle, Jenny Munro, Dr Adreanne Ormond and Professor Linda Tuhiwai Smith.

Thank you to Professor Johanna Wyn for reading an earlier draft of our book and providing insightful and encouraging feedback it was exactly what we needed and spurred us on to completion.

The Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund funded the research on which this book is based.

Thank you,

Karen Nairn, Jane Higgins & Judith Sligo

1

GROWING UP IN NEOLIBERAL TIMES

Young New Zealanders born in the years immediately following 1984 are the focus of this book. They are this countrys neoliberal generation, who grew up during economic and social policy reforms that transformed New Zealands economy and society. By one reading, out of these reforms fortress New Zealand became an open, internationalised economy capable of competing in the global marketplace. By another reading, the country abandoned its full employment goal and commitment to adequate social welfare provision in favour of privileging the market in allocating employment and resources. New Zealand was not alone in taking this path. Political leaders in the UK, US, Canada and Australia were similarly engaged in the neoliberal revolution during the 1980s. But New Zealand gained a reputation for going the furthest and fastest in the Western world in reforming its economy along these lines.*

Our intention is to explore how the generation born into this evolving landscape grappled with crafting identities and futures for themselves, particularly as they made the transition from school to their post-school lives in the mid-2000s. Like Ball, Maguire and Macrae (2000), who describe what neoliberalism meant for those growing up in Thatchers Britain, we explore what similar changes have meant in New Zealand for the children of Rogernomics (also see Andres & Wyn 2010; Gerson 2010).

We interviewed ninety-three young people twice (and in some cases three times) over a period of two years. Most were in their last year of high school when we first talked with them, although a small number had recently left school. Some participants returned to school the following year, but most had embarked on their post-school lives by the time we caught up with them for a second, and sometimes third, interview. This was a diverse group in terms of social class, ethnicity and school-leaving status, ranging in age from fifteen to early twenties. In bald terms, the structure of the group was as follows: seventy participants were young women, twenty-three were young men. Fifty-three were Pkeh,* twenty were Mori, fifteen were Pasifika (most of whom were born in New Zealand) and five were from new migrant families from countries other than the Pacific Islands. Overall, sixty-eight participants stayed in school until Year 13, although not all completed this final year of high school. Twenty-five left school before starting Year 13 (in New Zealand usually aged seventeen or eighteen) and, in this group, fourteen left before the beginning of Year 12 (age sixteen years or younger). They spoke with us about school, family, friends, work, career plans, tertiary education, leisure, spirituality and growing up. They shared hopes about their imagined futures and anxieties about whether they could make these futures happen. Two of our research sites, involving fifty-five participants, were urban: Auckland, New Zealands largest city, and Christchurch, the South Islands largest city. The third site, involving thirty-eight participants, was a provincial town servicing a rural area.

We were not attempting a statistical analysis of a strictly representative sample of New Zealand youth. This has been done superbly elsewhere (Adolescent Health Research Group 2003, 2008; Rasanathan, Ameratunga, Tin Tin, Robinson, Chen, Young & Watson 2008). Rather, we were seeking a rich analysis of qualitative data drawn from in-depth interviews with a diverse group. Our focus was the identity work of these young people. How did they craft their identities as they navigated transitions into new forms of adulthood? What role, if any, did the discourses of neoliberalism play in their identity work? What other discursive resources did they draw on to construct identities? How were their choices and aspirations shaped by forms of inequality and social exclusion in their communities, schools and families? What kinds of adulthood were they inventing? (Thomson, Holland, McGrellis, Bell, Henderson & Sharpe 2004).