At the conclusion of the Constitutional Convention in September 1787, a Philadelphia citizen asked Benjamin Franklin, What sort of government have you given us? Franklin famously replied, A Republic, if you can keep it.

The struggle to preserve the Republic has never been easy or without perils. The rise of political parties, which the founders opposed; the conflict between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans over how to respond to European turmoil from the wars of the French Revolution; and President John Adamss Alien and Sedition Acts repressing the press and free speech made Franklins conditional response seem all too prophetic. The 1800 election in which Thomas Jefferson was denounced as the antichrist and Adams was described as a hermaphroditehalf-man, half-womanmoved Jefferson to decry partisanship in his 1801 Inaugural Address and defend the first peaceful transfer of political power from one party to another by saying, We are all Federalists; We are all Republicans; We are all... Americans. The Civil War of 186165 was the greatest assault on the Republics ability to work out political differences peacefully.

But new perils lay ahead. Industrial strife, economic downturns or panics, and corruption plagued late nineteenth-century American politics. Henry Adams, the offspring of the great Adams family, argued in 1919s The Degradation of the Democratic Dogma that Americas democracy inevitably would collapse. The Teapot Dome scandal of the Warren G. Harding administration; the failure of Herbert Hoover to address effectively the economic depression of the 1930s; the disputes over foreign policy preceding World War II, including the battle to combat the anti-war isolationists preaching America First; postwar recriminations about communism at home and abroad; Joseph McCarthys ruthless invective in denouncing political opponents in the 1950s; the misguided commitment to the Vietnam War in the 1960s; the Watergate scandal in the 1970s that forced the only presidential resignation in history; the George W. Bush war in Iraq that never revealed weapons of mass destruction; and now the Trump administration that remains under investigation for corruption, and for welcoming Russian interference in the 2016 election, and for pressing Ukraine to investigate and denounce Joe Biden and his son, were evidence enough to impeach Trump and provide enduring support for Henry Adamss forecast.

These strains gave additional appeal to demagogues using mass media, through which populist leaders thrived. Their pronouncements on easy fixes to economic and social problems at home and shifting dangers abroad made them attractive figures to millions of people.

In 1959, the journalist Richard Rovere declared, We have been, by and large, lucky [in having few national demagogues but] there is no assurance our luck will hold.... For a nation that has known a good deal of mob rule and thatin its devotion to public libertiesmakes mobs quite easily accessible to demagogues, we have had, I think, remarkable good fortune in having had so little trouble.

The countrys attraction during the 1930s depression to Louisianas Huey Long, whom Franklin Roosevelt called one of the two most dangerous men in America (along with General Douglas MacArthur), and the subsequent affinity for Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthys anti-communist crusade that recklessly victimized innocent Americans, gave Rovere reason to think that our luck was running out.

The resistance to putting a demagogue in the White House held up during the anti-communist agitation of the 1950s and the Vietnam War in the 1960s. But Vietnam opened the way to Richard Nixons election in 1968, and Watergate once again tested the viability of our democratic institutions and the rule of law. Nixons resignation in August 1974 moved Vice President Gerald Ford, his successor, to declare, My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over.

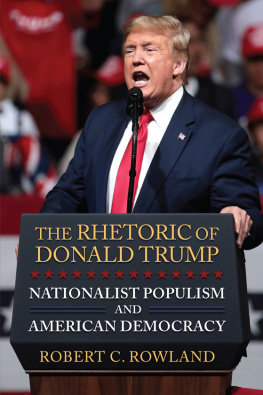

But was it? Donald Trumps 2016 election to the White House has presented a new challenge to our system of government. His lying about a host of things (over ten thousand lies, according to the Washington Post) has undermined his credibility and further weakened public faith in government or, more precisely, the way we govern ourselves. We are now in the fourth year of the Trump presidency and in the midst of another, perhaps more formidable, challenge to traditional republican institutions. And while it is still too soon to tell how this part of the story will turn out, or what the full impact of his administration will be on the American system of government at home and its relations with allies and adversaries abroad, it is already clear that this is not a conventional administration with a traditional chief executive mindful of constructive presidential actions, or respectful of the rule of law and the men and women who enforce it. As twenty-seven mental health experts argued in The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump, he is a deeply insecure man who needs to counter his sense of limits with a grandiosity that alleges his superiority in wealth and accomplishment to everyone. It is a troubling assertion of a false reality that threatens the national well-being.

What in our past politics and presidential administrations opened the way to this current assault on American democracy? And more important, what in our earlier history allowed us to create a reasonably well functioning system of governance that echoed Franklin Roosevelts assertion, Better the occasional faults of a Government that lives in a spirit of charity than the consistent omissions of a Government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.

It is the Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan presidencies discussed in this book that have advanced both the national well-being and the turn toward the troublesome Trump administration. To Trump, unaware of their histories, all these administrations were pretty much a blank slate. It was only with the George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama presidencies that he saw vulnerabilities he thought he could exploit to become president. Yet there were traditions in place that made Trumps ascent to the presidency and behavior in office possible. While each of these pre-Trump governments had distinctive qualities that separated them from their predecessors and successors, they shared defects that made them all, to one degree or other, architects of our present hopes and dilemmas. Some were certainly more complicit than others in giving rise to current events, but they are all worth considering as designers of present-day concerns.

None of this is meant to suggest that I will offer any exhaustive treatment of these modern presidential administrations. My focus is on aspects of these presidencies that served as preludes to Donald Trump. The George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama administrations are of obvious significance, too, in bringing Trump to the fore, but I feel these administrations are too recent to be fully open to convincing historical judgment. As a historian schooled in taking the longer view of events, I will largely confine this book to the administrations from Roosevelt to Reagan.

Lest I seem intent strictly on the underside of these presidencies, I intend to underscore the effectiveness of these presidents as well, and to inject a measure of hope into the current national malaise about politics. Our most successful presidents offered a realizable vision, used their understanding of politics and personal popularity to get there, built a national consensus to achieve their goals, and were mindful that their credibility was essential to their effectiveness. How Trump measures up to these standards is one way to think about his performance as president. In brief, these earlier administrations partly tell us how we got here. But they also underscore how different the Trump presidency is from what came before.