This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1991 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

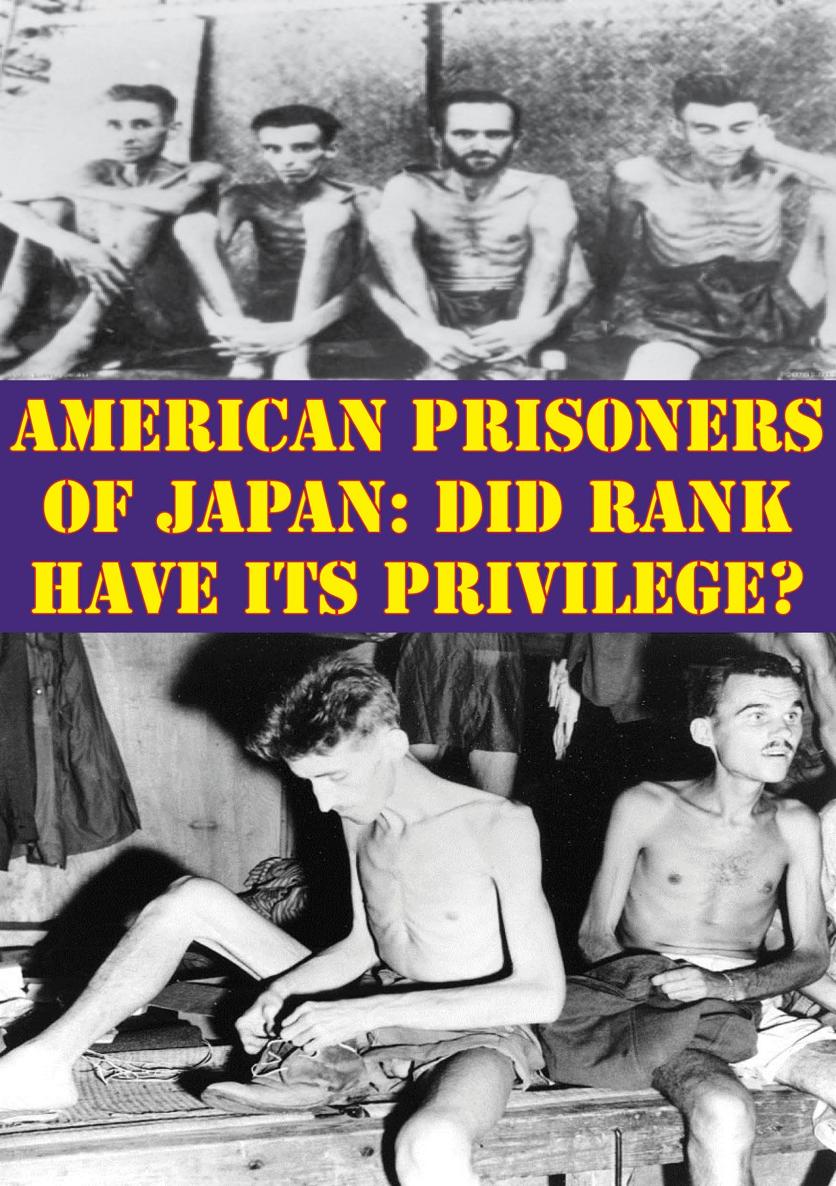

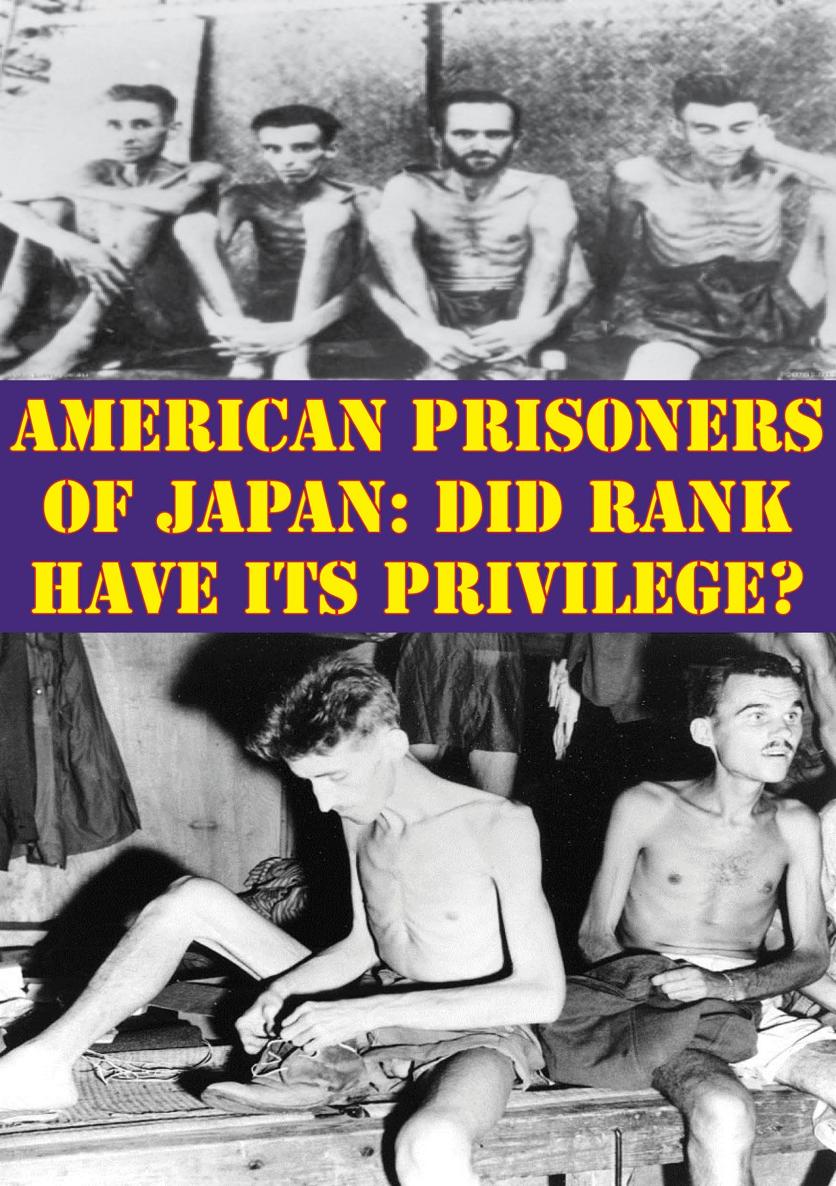

AMERICAN PRISONERS OF JAPAN: DID RANK HAVE ITS PRIVILEGE?

by

MICHAEL A. (BUFFONE) ZARATE, MAJ, USA

B.S., Cameron University, Lawton, Oklahoma, 1983

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

ABSTRACT

AMERICAN PRISONERS OF JAPAN: DID RANK HAVE ITS PRIVILEGE? by Major Michael A. (Buffone) Zarate, USA.

This thesis examines the story of American POWs held by the Japanese in WWII to see if there were significant differences in treatment based on rank. It examines how the Japanese treated the prisoners according to international law and also distinctions made by the officers themselves simply because of higher rank.

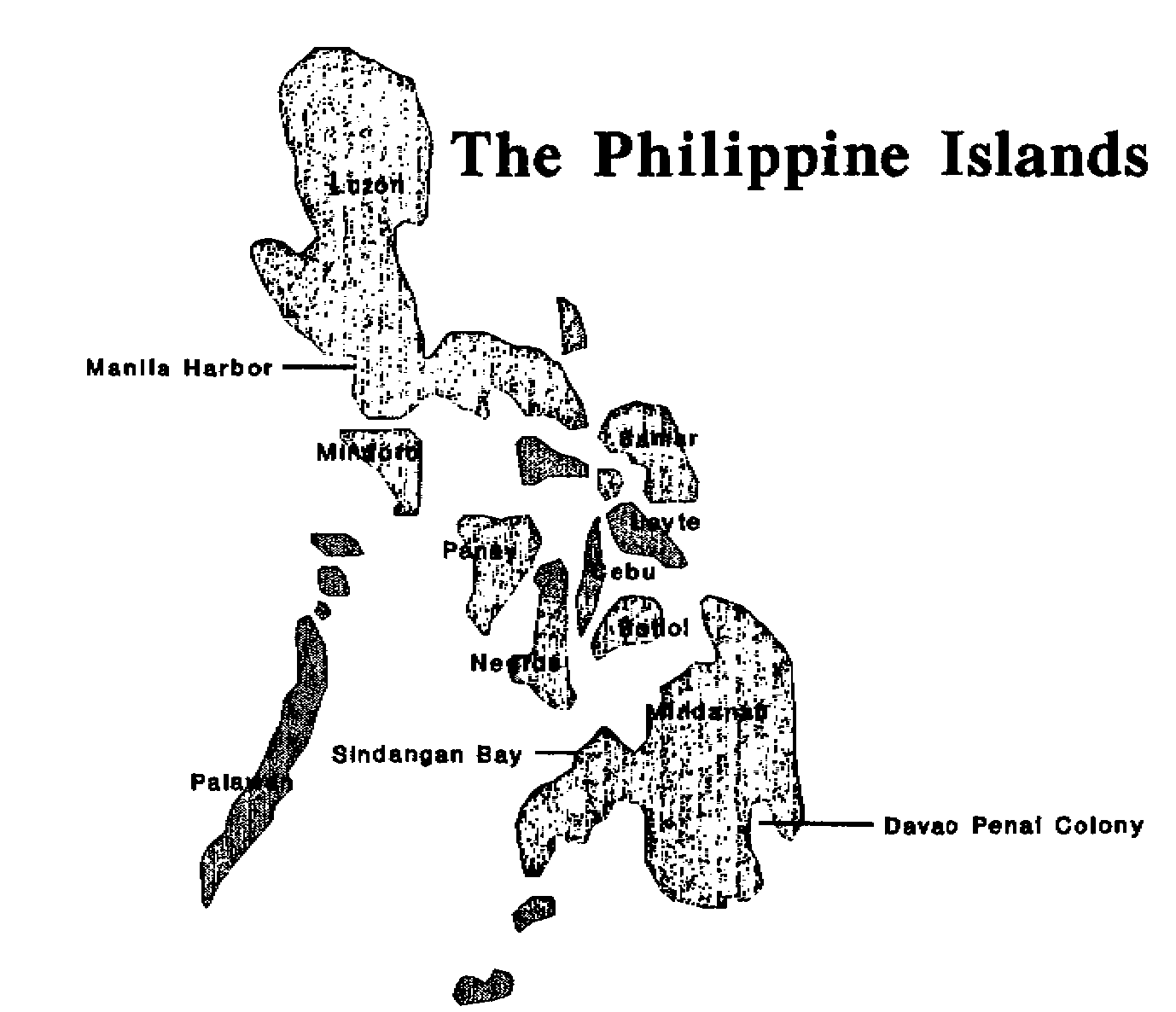

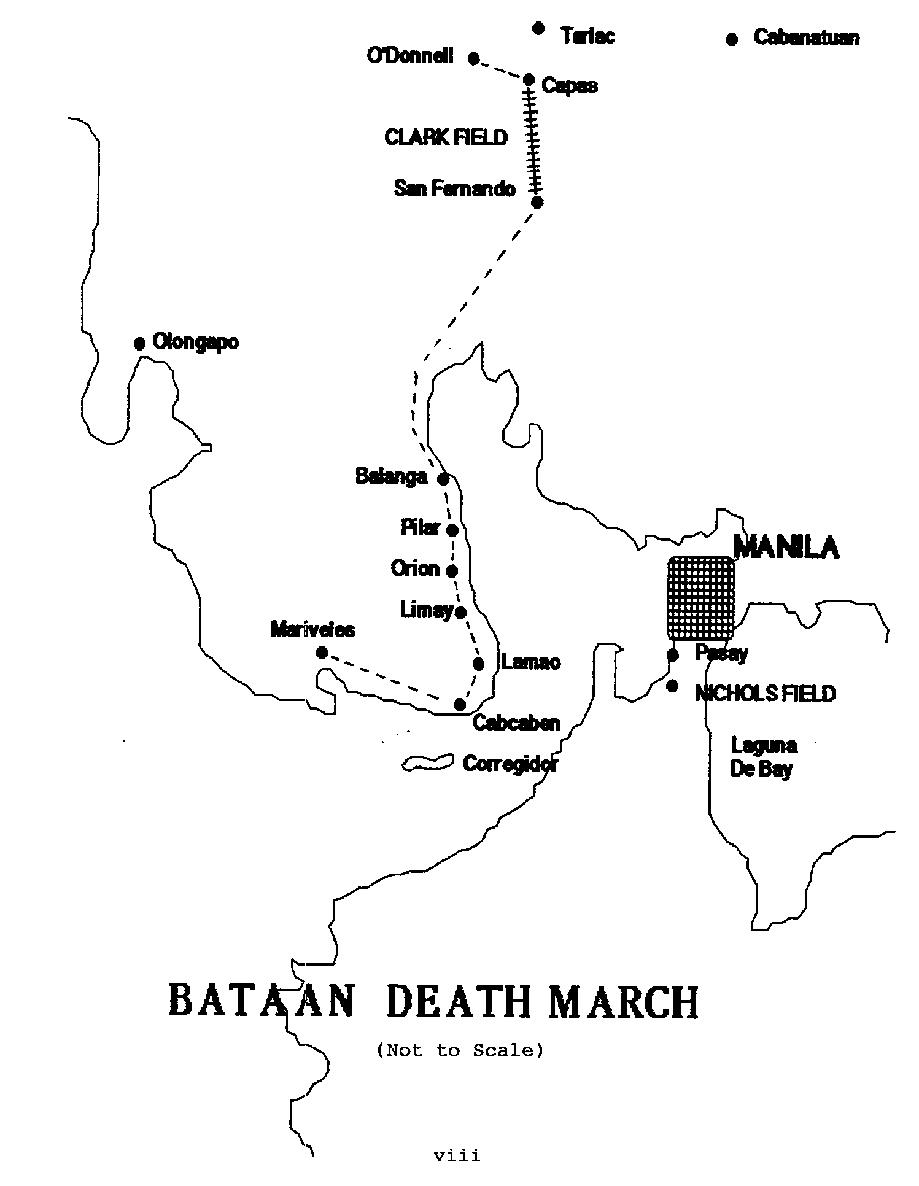

The thesis begins by discussing the historical framework for POW rank distinctions by looking at past wars and the development of rank distinctions in international rules. It then covers the American WWII POW experience in the Far East from Bataan and Corregidor to the wars end.

Special emphasis is placed on distinctions made in food, housing, pay, medical care, camp administration, work requirements, escape opportunities, transportation, leadership problems, and overall death rates.

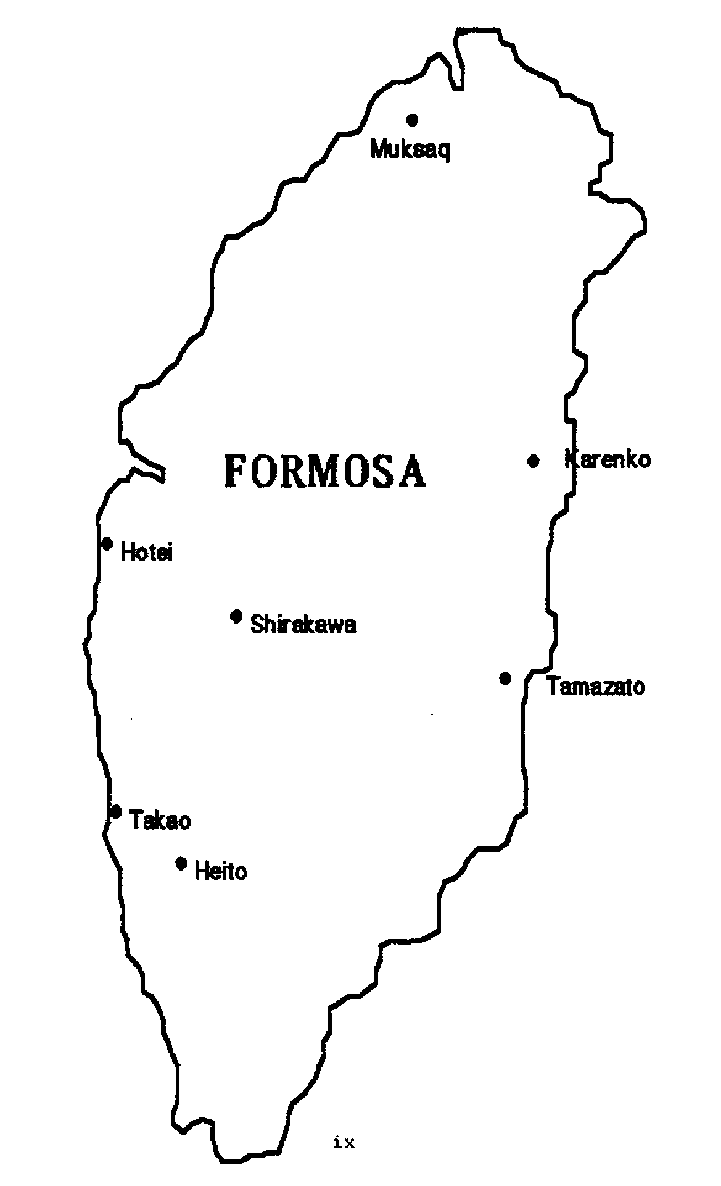

The study concludes that there were significant differences in treatment based on rank. These differences caused extremely high enlisted death rates during the first year of captivity. The officers fared worse as a group, however, because the Japanese held them in the Philippines until late 1944 because international rules prevented the Japanese from using officers in Japans labor camps. During shipment to Japan many officers died when the unmarked transport ships were sunk by advancing American forces.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I come from a family of warriors. My grandfather, Cosimo Buffone, emigrated from Calabria, Italy in 1910 and settled in Poughkeepsie, New York. A few years later he returned to Europe to fight with the allies in World War I. All of his six sons also enlisted in the U.S. Armed Forces. Vincent joined the U.S. Navy and fought in the Pacific in WWII. He died two years after the war ended in an industrial accident. Dommie joined the Army and fought in Europe. Frank fought in Burma and was a Combat Engineer during the Korean war. George also fought in Korea and later worked recovering downed helicopters in Vietnam. My father, Angelo, spent three tours in Guam during the Vietnam war. This thesis is dedicated to themthe warriors in my family.

Cosimo had another son who fought with the Army Air Corps during WWII in the Far East. His name was Louis Buffone and he was captured by the Japanese on Bataan in April 1942. He survived the infamous Bataan Death March and confinement in POW camps in the Philippines and Japan for over three years. I met Louis in 1982 and we corresponded for two years before he died of leukaemia in 1984. We talked very little about his experiences as a POW. I could see a distant pain in his eyes whenever the subject came up, but I sincerely felt he wanted me to know what he had endured.

As I researched the material for this thesis I tried to envision what Louis must have experienced. Through the eyes of others I felt his fear as Japanese soldiers brutally murdered the weak men who could not keep up on the march. I felt his parched throat crying out for water as the hot sun burned down on his head. I drank foul water from a carabao wallow where the bloated bodies of less fortunate men had fallen to their final rest. I saw the endless procession of emaciated bodies being taken to the shallow graves at Camp ODonnell. I watched Louis spend agonizing hours bent over the rice fields of Cabanatuan. I descended with him into the vile holds of the Hell Ships and later into the chilling blackness of the coal mines of Fukuoka. I stood by his side and smelled the acrid smoke from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima as it passed slowly over his camp. I cried tears of joy with him as American planes dropped barrels of food by parachute into the camp when the war ended. He could not tell his story so I have told it for him.

I would also like to dedicate this work to another man who holds a special place in my heart. He is my father-in-law, William Marion Kirby, Jr. While Louis labored in a prison camp under the Japanese, Marion Kirby was also in a prison camp under the Nazis in Germany. He was shot down late in the war during a night photo-reconnaissance mission over Cologne. I have never met a person with more love for his family and compassion for his fellow man.

Many people assisted in the preparation of this thesis. I would like to thank John Homerin and David Ifflander for their genuine encouragement throughout the year. I would especially like to thank Ed Fallon for his patient, listening ear. I could always count on him for ideas and advice. I would also like to thank Chris Ellis and John Herko for help in making the maps which appear in this thesis.

Special thanks to Colonel (Retired) Johnny Hubbard for taking some of his valuable time to read the final draft and adding his suggestions for improving the final product.

I am indebted to the members of my committee for the long hours they spent reading, editing and prodding me along. I am grateful that they were patient and could see that beneath my hard head lies a soft heart.

Finally I would like to thank my wife, Melinda, for hot coffee, proofreading and patience. But mostly I want to thank her for recognizing when my mind had wandered too deeply into the abyss and for gently jerking me back to reality.

Louis Buffone identified himself to me as the POW seated at the end of the row in the photo above. This photo appears in the official U.S. Military history, The Fall of the Philippines , by Louis Morton.