Contents

Guide

Page List

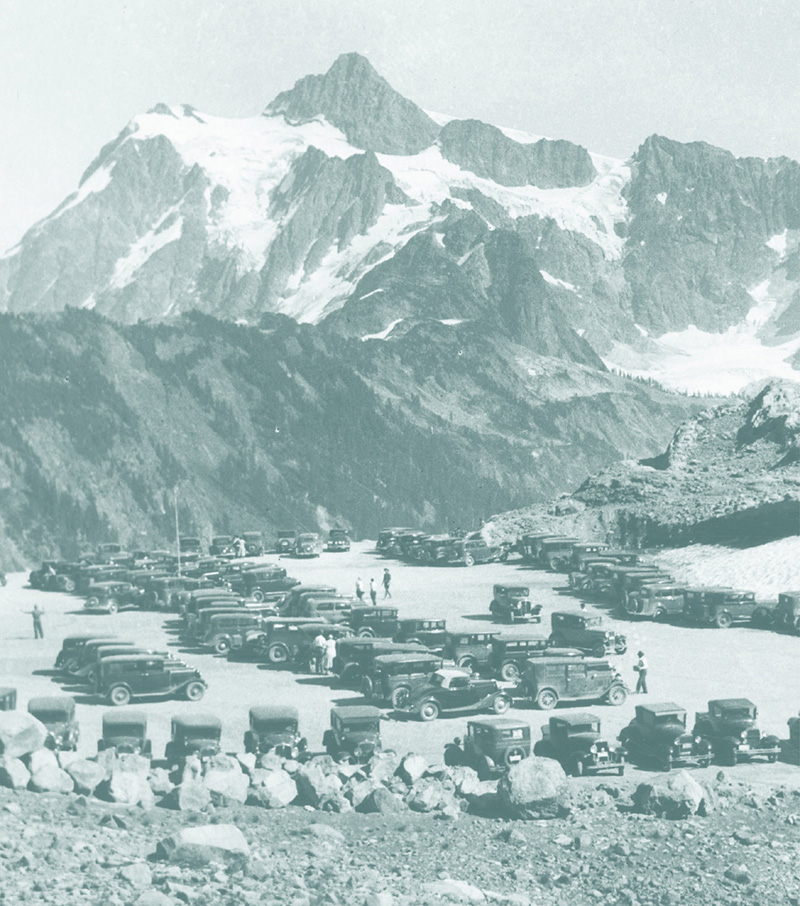

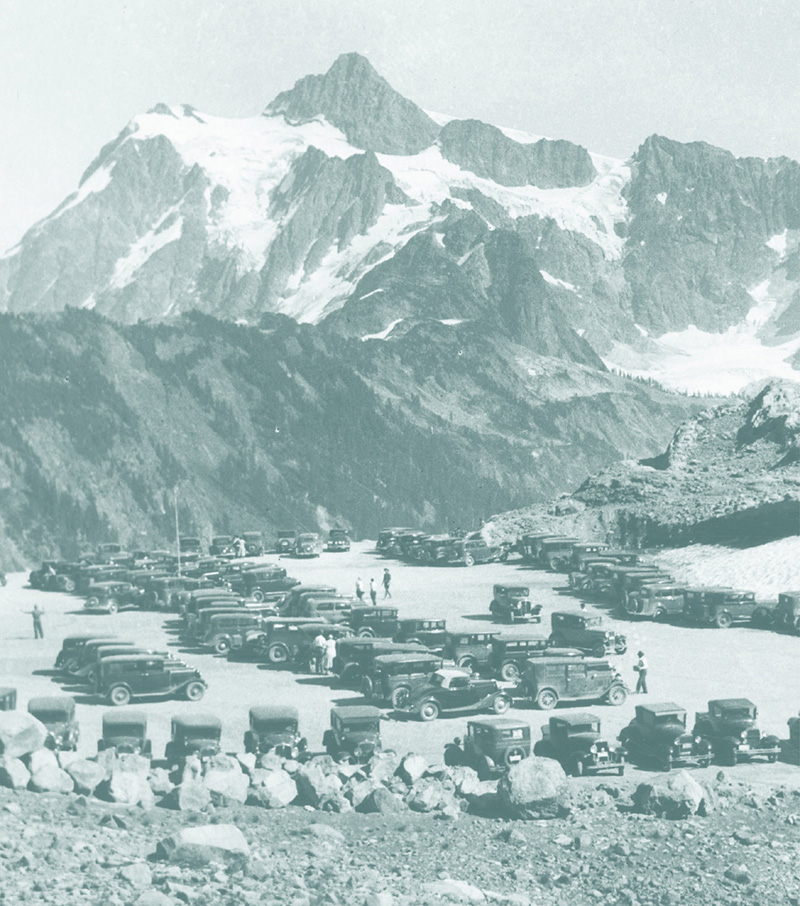

Even in the early days of national forest recreation, parking was a hassle, as seen in this 1935 photo on the Mount Baker National Forest in Washington State.

OUR

National

Forest

STORIES FROM AMERICAS

MOST IMPORTANT PUBLIC LANDS

GREG M. PETERS

Foreword by

MARY MITSOS, NATIONAL

FOREST FOUNDATION

To all the national forest fans out there; the employees of the US Forest Service with whom Ive worked over the years and who taught me that the agency is made up of committed, caring individuals working tirelessly for the benefit of the forests and the American public; the communities that rely on these lands for water and livelihoods; and the forests themselves. Also to Mom, who (among so many other things) helped me become a better writer all those years ago; to Dad, who took me camping in sun, rain, and everything in between; and to my wife, Chrissy, whose unwavering support gave me the confidence to embark on this project and to see it to completion.

A mountain biker descends a trail through the red-rock topography of Utahs Dixie National Forest.

CONTENTS

Some individual forests have been administratively combined in recent years. For example, the various forests in Alabama are now collectively called the National Forests of Alabama and the names listed here are now considered ranger districts, not distinct national forests.

FOREWORD

A COOL, CLEAR MOUNTAIN STREAM. A wide open prairie of waving tall grasses. A majestic range of western peaks covered in ponderosa pines. These are some hallmarks of Americas cherished national forests.

But, if we look more closely and shift our lens from macro to micro, a very different world comes into view. It is the world of a small child cradling a butterfly. A family sitting on a riverbank watching the water flow. A solitary hiker quietly stepping along a mossy trail.

The pages that follow reveal both perspectivesthe grand and the miniscule, the awe of world-class scenery and the amazement of personal discovery. At 193 million acres, our National Forest System is the centerpiece of Americas public lands. It was originally conceived during the great clear-cutting of our countrys forests in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In fact, this massive harvesting of our forests, many of them virgin lands, exposed the pressing need for a more sustainable path.

When the US Forest Service was established, it was charged with providing a renewable source of timber and clean water to a growing nation, both still integral parts of the agencys mission 115 years later. Over time, the system grew, as did Americans understanding of why areas needed to be set aside for public good. Even the concept of public good expanded. By the mid-twentieth century, outdoor recreation was popular, and increasing mobility and middle-class means led millions of Americans to visit scenic places that previously were just images on postcards.

In recent decades, two major shifts have further demonstrated the relevance and importance of national forests. As a nation, we finally recognized that these public lands are not equally shared by all Americans, and the challenge of ensuring a diversity of Americans can engage in these places became ever more pressing. Through efforts to tell more inclusive histories, major outreach initiatives, and programs to link urban population centers with more remote forests things are starting to change. Though long overdue, we are telling the entire story about how National Forest System lands were originally the homelands of indigenous peoples.

The second shift is all around usour changing climate. National forests are natural carbon sinks, increasingly seen as integral parts of natural climate solutions. The National Forest Foundation and many others are aggressively planting trees to help maintain the intactness and resiliency of our public lands; this is critical now, as our forests are stressed by unnaturally large fires and other disturbances, which compromise their ability to harbor healthy wildlife, provide clean air and water, and store vast amounts of carbon.

As the peoples lands, national forests are a vital part of a vital idea: that ordinary citizens, not the wealthy or well connected, own these places of beauty, of sustainability, of personal renewal. Our nation essentially created this concept of public lands. But it is a fragile idea. We must be willing to accept the mantle of stewardshipof real careto ensure national forests endure.

The National Forest Foundation and many like-minded nonprofit organizations exist to foster meaningful personal connections to our forests. Our conservation projects, whether restoring a watershed or taking out young people to learn about the unique ecology of tallgrass prairie, make meaningful change on the ground. These projects also cultivate a deeper understanding and commitment among our fellow citizens so they, too, can become essential stewards of this amazing, uniquely American, legacy.

Whether its the lowland swamps of coastal Carolina, the arid and rugged beauty of our Southwest, or Colorados iconic snowy peaks, these incomparable places help define Americas identity. They tell stories, reveal ancient patterns, and shape the communities in their shadows. They are places to admire, to explore, and, ultimately, to protect.

I hope this book takes you on a journey of discovery that opens up the richness and relevance of our national forests.

Mary Mitsos, President, National Forest Foundation

PREFACE

OUR BLUE SUBARU IMPREZA RATTLED up the rutted dirt road, its headlamps piercing the nights darkness. My girlfriend, Chrissy, sat quietly in the passenger seat. I knew she was anxious. I was too.

We had no specific destination and drove ever deeper into the dark with the base understanding that the road led to a national forest. I didnt even know, in any meaningful way, what a national forest was, only that they reportedly allowed free camping and imposed few limits on where you could pitch a tent for the night. The day had been wearisome, and we longed to be out of the car and in our tent.

An hour and a half had passed since we had rolled through Billings, Montana, in the waning evening light. We couldnt afford a hotel room in the city and had planned on finding a spot to camp. The ragged gazetteer we employed for our road trip indicated that a national forest lay to the west of Billings, so we took the closest exit and motored into the growing darkness.

Eventually, we decided we were on the forest. I cant recall, nearly two decades later, which forest we thought we were on, or if we passed a sign that told us. I pulled over in a turnout that seemed flat enough to accommodate our small tent and we set up our camp.