Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

To Claire, Edith, and Nina, with all my love,

and for whom all choices are made.

INTRODUCTION

The Choice We Face

ONE DAY IN APRIL 2015 , I attended a town hall about the future of Burke High School, a historically Black public high school in Charleston, South Carolina. At the time, I was a faculty member at the College of Charleston, teaching classes on the history of education and the civil rights movement. The meeting piqued my interest. It was organized by local White parents who demanded reform to improve Burke High. Though the school was modern and within walking distance for most students, most Whites refused to send their children to the school, citing subpar test scores, poor teaching, and a weak curriculumperceptions that were not always supported by research. The nominal purpose of the meeting was to improve a Black high school. But what was really at stakeas what is at stake at most meetings of this kind that occur every week in communities across Americawas the heart and soul of public education.

The room was crowded by Charleston standards. Over two hundred people were in attendance. The fact that nearly half the crowd was Black made it one of the rare integrated meetings in the city. It was classically local and grassroots. Notice for it was publicized by word of mouth and through Facebook, the preferred social media of parents in Charleston, if they used any at all.

Burke High School was founded as the Charleston Industrial Institute in 1894. It is the only high school that remains a traditional, noncharter public high school on the peninsula of Charleston. It is also 97 percent African American. Racially, the school stands in stark contrast to the popular historic homes that surround it, which are mostly occupied by Whites. The gentrified neighborhoods of Charleston are now over 70 percent White, a dramatic shift since the 1980s, when the city was two-thirds Black. The city, historically, was predominantly Black. Before the Civil War, the numbers of enslaved African Americans outnumbered Whites by at least two to one, at times five to one. Charleston is now the whitest it has ever been in history. Though Black parents and community members have long labored to improve Burke, the concerns of White parents who called the meeting seemed to garner more attention. These underlying truths and the dramatic gentrification of this historically Black city added to a palpable tension in the room.

Moving in droves since the early 2000s to this newly discovered tourist destination, Whites wanted better options for their kids. Burke High Schools reputation, like that of many segregated Black schools, left much to be desired. The school was consistently tagged as at risk or failing. Unfounded rumors of violence and inept teaching circulated among White Charlestonians. Alternatives to Burke were appealing yet limited. The magnet schools serving middle and high school students in the area were great but were very difficult to get into. The local paper, the Post and Courier, likened entry into the premier Charleston schools to admission at Harvard. The private Porter-Gaud School is indicative. Porter-Gaud is routinely lauded as one of the best in the state and enjoys status as a nationally ranked private school. It is also one of the most expensive, with tuition for the lower school set at $22,000 per year.

Avoiding Burke and largely excluded from the alternatives, parents demanded more choice. Like other gentrified areas across the country, Charleston embraced charter schools as a way to provide more choice with wide support among both African Americans and Whites. In fact, a Black alumnus weeks before the meeting submitted a proposal to convert Burke into a charter school. The proposal, driven by a growing desire among Whites to use the public schools if they were chartered, was almost guaranteed success. The last public high school standing in Charleston was about to become a charter school, and the meeting set the stage for how the debate would unfold.

Public education and the politics surrounding it were personal for me. My wife and I are White. We were then without children. But if and when we did have children, we had decided to commit to using the public schools in the area. We would have skin in the game, as problematically White as it was.

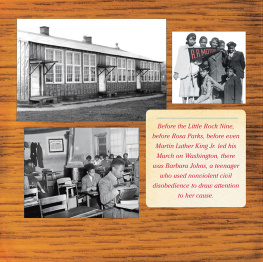

I was also captivated intellectually, which only fueled my interest in the future of Burke High School. The school was for me steeped in symbolism and significance. With my students I studied the history of education in South Carolina and the struggle to achieve a quality education, one of the hallmark struggles of the Black freedom movement. In 1740, it became illegal to teach African Americans in South Carolina. After the Civil War, a paltry education was reluctantly offered, provided it was segregated. During the civil rights movement, Whites vehemently resisted integration, putting forth insidious mechanisms to preserve their privileges and investment in a segregated system, most notably through freedom of choice plans that eventually included charter schools.

The deeper meaning of events was obvious to me. At the center of debate was school choice. As school choice advocates and some scholars have noted, choice or the principles behind it have existed since the earliest years of our republic. Philosopher John Stuart Mill warned of state intervention in education. Other theorists, including Thomas Paine or even Adam Smith, have backed the use of vouchers or public support for private education. It has been noted that states such as Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine (which has covered some of the cost of private school tuitions since the 1870s) supported vouchers over 150 years before the Brown decision. And across the country parents practiced choice to some degree when they enrolled their children in a private school, which was often religious in nature, most notably Catholic. Choices driven by a market existed over a century before the founding of a common public school system in the United States.

But school choice as understood and practiced today is an education policy that took on new significance in the politics of massive resistance after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. Calls for vouchers and minimalist state intervention prior to Brown occurred when schools were segregated by race in the United States or, before 1865, when formal education was denied to Black families. Race and racist policy after Brown have shaped the emergence of school choice and are inextricably linked to its contemporary manifestation. Segregationists used vouchers along with an ideology of choice that fundamentally shaped what we mean by choice today. Vouchers and calls for subsidized private education fell into the hands of influential segregationists after Brown. This is not to say that everyone who discussed vouchers in the 1950s was racist. However, to ignore the determining role of race and the politics of massive resistance or to claim that the origins of choice are not racistas so many have done and continue to dois to conceal problematic and paradoxical development of school choice over time. Such myopic definitions ignore the very premise of public education in the United States, which was indelibly shaped by racist policy.

As practiced today, school choice allows parents to select alternatives to their local public school to improve all schools through competition. Since the