Copyright

2019 University of Hawaii Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hubbert, Jennifer Ann, author.

Title: China in the world: an anthropology of Confucius Institutes, soft power, and globalization / Jennifer Hubbert.

Description: Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018036238 | ISBN 9780824878207 (cloth; alk. paper), Kindle 9780824878559 EPUB 9780824878542 PDF 9780824878535

Subjects: LCSH: Kongzi xue yuan. | Chinese languageStudy and teachingForeign speakers. | Chinese languageGlobalization. | Cultural diplomacyChina.

Classification: LCC PL1069.K66 H83 2019 | DDC 306.441/951dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018036238

University of Hawaii Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources.

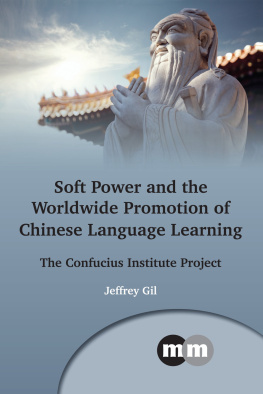

Cover photo: Statue of Confucius at the Imperial College (Guozijian) in Beijing, China (October 18, 2015). beibaoke / Shutterstock.com

I scarcely know where to begin in acknowledging the intellectual and personal sources of inspiration amassed over the years spent researching and writing this book, although I must begin with the hundreds of students, parents, teachers, and administrators in the Confucius Institute programs I have interviewed over the years and the schools that have hosted me. By necessity these educational institutions and interlocutors remain anonymous, but my heartfelt thanks to those who patiently explained the Chinese programs to me, shared their joys and concerns, hopes and sorrows, cannot be overexpressed.

I first conceptualized this project over a long writing retreat weekend with two other anthropologists who have over the past twenty-plus years become central to my intellectual endeavors and general well-being. Lisa Hoffman and I met when my oldest child, who graduated from college the year this book went to press, was not yet walking, and we began writing our dissertations together. We added Monica DeHart to our mix a few years later and spent the next several decades meeting at roadside truck stops, bed-and-breakfast inns, remote cabins, and anthropology conferences to swap manuscripts and ponder the curveballs of life. Their imprint rests on each page of this book and my debt to their collaborations over the years knows no bounds.

Others over the years have read and provided vital commentary on various pieces of this manuscript. Jennifer Hsu, Oren Kosansky, Dawn Odell, and Eileen Otis offered sound suggestions on different chapters, and David Campion reined in my vocabulary excesses. A special thank-you goes to Anne Grossman, who dragged me out of my office (not often enough) to work in brighter venues. I am pretty sure that over the years we lugged our computers to every coffee shop and wine bar in town. The gracious anonymous reviewers of this manuscript similarly deserve recognition and gratitude for pointing out my theoretical inconsistencies and directing me to potential reader misunderstandings. All remaining imperfections are, of course, my own. viii

I have long felt as if I won the job lottery with my position at Lewis & Clark College. My colleagues have been intellectually stimulating and always supportive and my students inspiring in their enthusiasm for knowledge; collectively they have listened to numerous talks on the subject of Confucius Institutes, have provided excellent feedback, and are mercifully consistent in sending me links to news media on the subject that I might have missed. I would also like to express my gratitude to Lewis & Clarks Office of the Dean, which supplied research money over the years, and to Lorry Lokey, whose Faculty Excellence Award provided much of the financial support needed to complete this project.

Portions of this book were presented at the University of Oregon, the University of Southern California, and assorted annual meetings sponsored by the Association for Asian Studies, the American Anthropological Association, and the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, and my deliberations on the subject have benefited from audience feedback at these venues. were published by the University of Southern Californias Center on Public Diplomacy working paper series (2014).

Lastly, my foremost and most heartfelt thanks belong to my family, who over the years of research and writing this book have suffered through long periods of both physical absence and mental absentmindedness. My two children, Nathan and Isabelle, now young adults off on adventures of their own, have been models for me of intellectual curiosity and compassion, and Jay, who was instrumental in encouraging me to pursue my interest in anthropology way back when, has always been a stimulating intellectual companion, gentle critic, staunch supporter, and very, very patient spouse. Your pesto pastas have nurtured my appetite and my soul.

x

CHAPTER 1

An Anthropology of International Relations

In December 2014, I attended the American Anthropological Association meeting in Washington, DC, to present a paper on Confucius Institutes as a form of globalization. Confucius Institutes (CIs) are Chinese culture and Mandarin Chinese language programs that are funded by the government of the Peoples Republic of China (PRC), staffed by Chinese nationals, and exported around the world. According to their mission statement, CIs were created to answer the interest of the global community in learning Chinese and to use educational and cultural exchange to promote global friendship. By ultimately establishing language and culture programs in all corners of the globe, CIs hope to reach two lofty goals: the development of multiculturalism and the construction of a harmonious world (Hanban n.d., Constitution).

Confucius Institutes, however, are not simply language exchange programs, but also the centerpiece of Chinas soft power policiesthat is, its attempts to win the hearts and minds of target constituencies through attraction to its culture and ideals rather than coercion or force.

The timing of my Washington visit could not have been more fortuitous, for the day after my arrival, the House of Representatives Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations held a congressional hearing to discuss Chinas soft power projects. According to the chair of the committee, Representative Chris Smith (Republican, New Jersey), the hearing was the first in a series intended to investigate whether Chinas soft power initiatives are undermining academic freedom at U.S. schools and universities. In particular, he announced, the committee would examine the myriad outposts of Chinese soft power that have opened on campuses throughout the United States and the world, the so-called Confucius Institutes, whose curriculum integrates Chinese Government policy on contentious issues such as Tibet and Taiwan and whose hiring practices explicitly exclude Falun Gong practitioners, a spiritual organization the Chinese state considers a threat to national security. The central question facing the committee, he announced, was whether American education is for sale: Are U.S. colleges and universities undermining the principle of academic freedom in exchange for Chinas education dollars? (US Congress 2014, 12). Smiths question mirrored broader debates among scholars, journalists, educators, parents, students, school administrators, and government officials about propaganda, national interests, and freedom of thought and expression in US classrooms that have raged since the very establishment of CIs in 2004. Yet the congressional hearing also made evident that critics of the CIs were responding to the institutes not only as language programs but also as a reflection of Chinas changing place in the world and perceived threat to extant global hierarchies of national power, and hence, by default, of the changing relative place of the United States. China, as manifest in the CIs, these hearings and debates suggested, was attempting to become a new model of modernity and globalization for the world and was posing a symbolic challenge not only to US education but also to US hegemony and the nations ideals for and ideologies of globalization, modernity, and the global order.