Table of Contents

Guide

THE TRIUMPH OF BROKEN PROMISES

Copyright 2022 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First printing

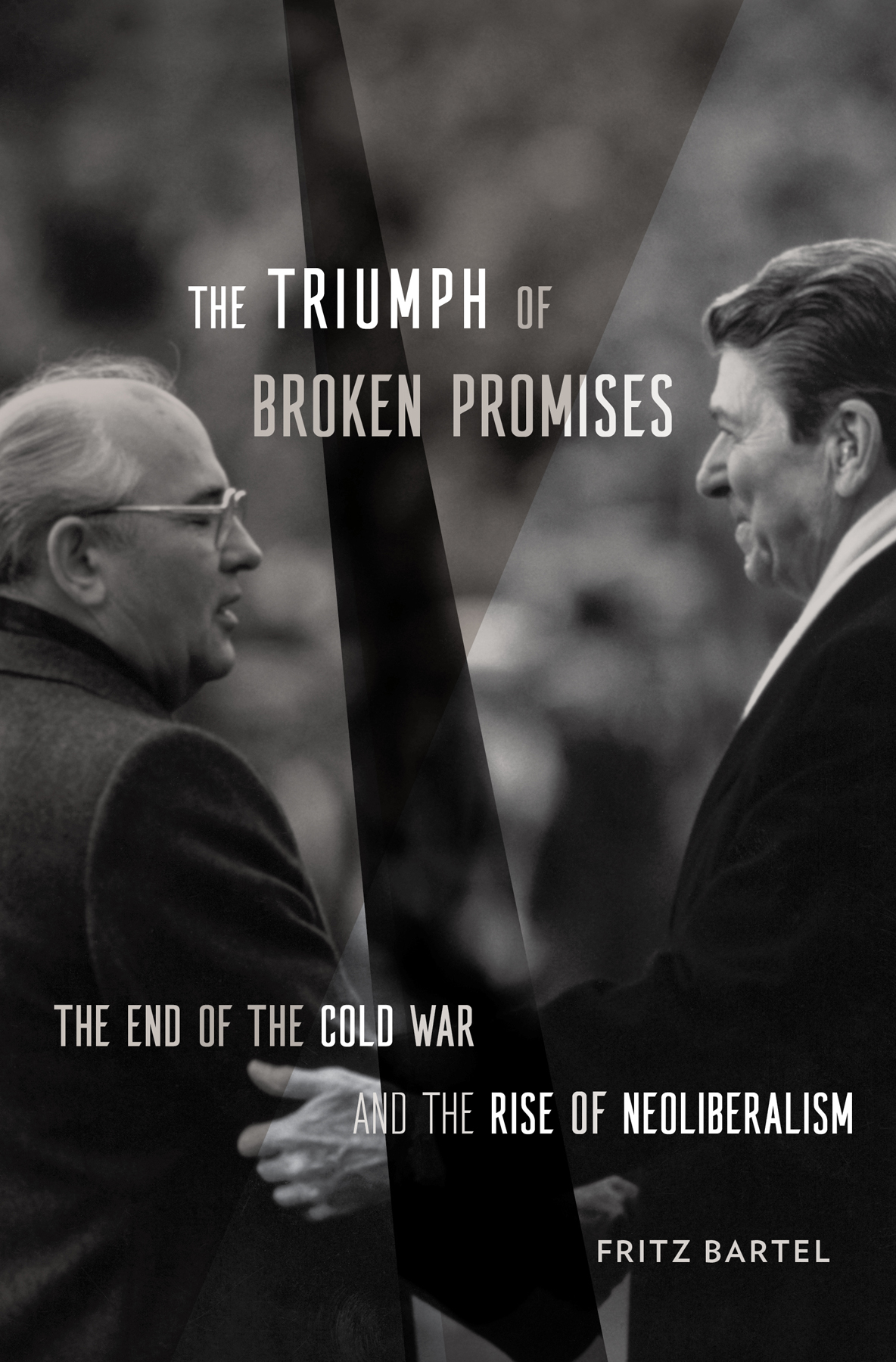

Cover photograph by Wally McNamee / Getty

Cover design by Lisa Roberts

978-0-674-97678-8 (Cloth)

978-0-674-27581-2 (EPUB)

978-0-674-27580-5 (PDF)

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Names: Bartel, Fritz, author.

Title: The triumph of broken promises : the end of the Cold War and the rise of neoliberalism / Fritz Bartel.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021045328

Subjects: LCSH: Neoliberalism. | Cold War. | RecessionsHistory20th century. | Financial crisesHistory20th century. | CapitalismHistory20th century. | Communist countriesEconomic conditions20th century.

Classification: LCC HB95 .B367 2022 | DDC 330.12/2dc23/eng/20220104

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021045328

To Mom, Dad, Mitch

and Amanda

CONTENTS

THE TRIUMPH OF BROKEN PROMISES

AS CHRISTMAS CAME to Europe in 1989, those who had long lived under the yoke of communism had many reasons to celebrate. In quick and unexpected succession, the authoritarian governments that had ruled over the eastern half of the continent since shortly after the Second World War had peacefully collapsed. Citizens who had long resisted communisms countless injustices had begun to take their place in the governing chambers of Warsaw, Budapest, and Prague. On the night of November 9, the Berlin Wall had fallen, vanquishing the most oppressive symbol of Europes division and Eastern Europes captivity. East German citizens, separated for four decades from their freer and richer countrymen in West Germany, had begun to use a new slogan of unityWir sind ein Volk (We are one people)and German reunification looked to be a real possibility for the first time since the early postwar years. In Moscow, Soviet general secretary Mikhail Gorbachevs launch of glasnost and perestroika had transformed Soviet society, set Eastern Europe free to choose its own fate, and allowed all Europeans to imagine a future in which they lived in one common European home rather than two antagonistic blocs. In Washington, former US president Ronald Reagan had worked with Gorbachev to strive for a world free of nuclear weapons, and his successor, George H. W. Bush, would soon speak of a new world order that might yet deliver permanent peace and prosperity to a weary but hopeful world. Taken together, the evidence of political progress was so swift and overwhelming that observers had begun to speak of 1989 as an annus mirabilis, a year of miracles. After decades of stolid oppression, winds of hope and renewal were in the air.

But Lszl Kzdi did not care. The end of the Cold War may have been a momentous development in the grand scheme of history, but it was little solace for Kzdi, a Hungarian pensioner living in Budapest, as he watched his economic security evaporate before his eyes. The Hungarian government was making life across the country worse with each passing day, and Kzdi could feel it. Government officials had announced that pensioners would be receiving a Christmas bonus to ease their economic woes, but the temporary cash infusion paled in comparison to the rising cost of everything in Hungarian society. By mid-December, Kzdi was fed up, and he took to the pages of one of the countrys leading newspapers to express his displeasure in an open letter to the nations chief financial official. Minister of Finance Lszl Bkesi! he began. I am turning to you with the following respectful request: With the Christmas bonus... please also send me an appropriately long and sturdy rope as an extra gift. I do not think I need to detail what purpose this rope will serve.

Kzdi explained that he had earned his current state pension through forty-two years of hard work. Under the communist government, that pension had provided Kzdi with a comfortable, if unglamorous, life. But now the times were changing. Recently, the government had begun to raise prices on everything. Gas, electricity, mortgages, food, public transportation, and even medicine were all becoming more expensive. These price increases left Kzdi in a desperate bind, he wrote, unable to afford a decent human life. The grim prospects left him no choice but to contemplate the end of his days and make his special request. Respected Mr. Bkesi! he concluded, to lighten the burden on the state budget, I repeat my request: Please issue the extra bonus, a strong rope, to me. Thank you in advance, Lszl Kzdi.

It was no accident that Kzdis biting missive appeared at a time of profound political change. Economic disciplinebroadly defined as government policies that intentionally cause domestic economic hardshipwas the cause of Kzdis sarcastic anger, and it was a potent political force in the last two decades of the Cold War.

Despite their efforts at avoidance, leaders on both sides of the Iron Curtain were hit with the political flak of economic discipline many times in the 1970s and 1980s. This book is a history of why those moments of discipline arrived and how they produced two of the defining global transformations of the twentieth century: the peaceful end of the Cold War and the rise of neoliberal capitalism. Scholars have produced insightful work on both of these transformations, but they have not yet understood them as interconnected products of a shared historyspecifically, the history of the world economy in the late twentieth century. Historians of neoliberalismwhich I will define as a political ideology that to increase the free flow of goods and capital across state borders, increase inequality within nation-states, and limit the states role in the provision of economic and social security for its citizenshave long traced its intellectual history, but they have paid less attention to how its rise intersected with the Cold War.

This book aims to recover that role by focusing on three of the forces that dominated global political economy in the late twentieth century: energy, finance, and economic discipline. All three forces rose to prominence in the wake of the oil crisis of 1973, which is where our story will begin, and their intertwined histories over the following two decades significantly contributed to the end of the Cold War and the rise of neoliberal capitalism.

The histories of energy, finance, and economic discipline provide powerful analytical tools for examining these transformations because their widespread emergence in the 1970s and 1980s profoundly shifted the political, economic, and ideological terrain on which the Cold War was fought. When the conflict began in the 1940s, democratic capitalist and state socialist governments had raced to expand the social contracts that prevailed in their societies in order to win the hearts and minds of their populations. They had raced, in other words, to promise their people a better life and deliver on that promise. After the economic horrors of the Great Depression gave rise to fascism and world war, it was a fundamental premise of political life in both East and West after 1945 that a governments chief domestic responsibility was to harness the forces of industrial modernity to improve the economic security and well-being of its people. Democratic capitalism and state socialism stridently disagreed about what mix of security and prosperity was bestunable to match the Wests prosperity, communist governments promised their citizens greater economic securitybut their difference was one of degree, not of kind. Whether communist or capitalist, governments in the first two and a half decades in the Cold War raced to expand their social contracts.