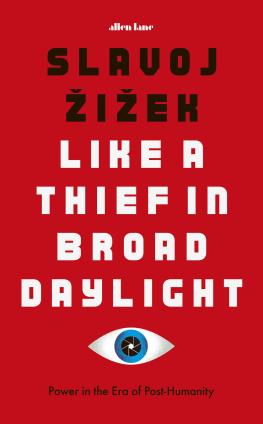

DOMINIC FRISBY

Daylight Robbery

How Tax Shaped Our Past and Will Change Our Future

Contents

About the Author

Dominic Frisby was born in London and educated at the University of Manchester. He is a financial writer who has written two books, Life After the State and Bitcoin; the latter Sir Richard Branson recommended as, A great account. Read it! He is a contributing writer for Moneyweek and also writes for Virgin and the Independent. He speaks at conferences around the world on the future of finance. Frisby hosts various podcasts including the Virgin Podcast, performs stand-up comedy and is a recognized voiceover artist.

For Samuel, Eliza, Lola & Ferdie

I love you all so dearly

Chapter 1

Daylight Robbery

The art of taxation consists of so plucking the goose as to obtain the most feathers with the least possible hissing.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, finance minister to Louis XIV (166183)

It was the early 1690s and the king needed money.

King William and Parliament had brought this problem on themselves. To gain popularity they had just got rid of a hated tax. Now he was short of cash.

What to do?

Every home had a hearth, and the English had been paying hearth taxes one way or another, usually to the church, since before the Norman invasion of 1066, when they were known as smoke-farthings or fumage. But in 1662, hearth money became statute. Every home worth more than 20 shillings (about US$5,000 in todays money) They demanded entry into peoples homes every six months to count their fireplaces, and so infringed on the Englishmans sacred privacy. Worse yet, the idea had come from France. The English hated it, and it was a huge source of grievance when the Glorious Revolution came in 1688.

Here was a means to quickly ingratiate the new monarchs, William and Mary, with their people. They abolished hearth money to erect a lasting monument of their Majesties goodness in every hearth in the kingdom.

But it left a major problem. The Dutch were owed money for equipping Williams invasion to overthrow the previous king, James II. There was conflict in Ireland and war on the Continent, the Nine Years War, to be paid for. There were allies of James II in Scotland to expel. There was also the small matter of a currency crisis at home.

How to pay for it all?

In 1696, a solution was found. Surprise, surprise, it came in the form of another tax: the Duty on Houses, Light and Windows. Otherwise known as the window tax.

Now a collector could walk past somebodys house and count the number of windows from outside. He didnt have to venture in. No privacy was violated. No engagement with the taxpayer was required, nor any declaration on his part. You cant hide windows, so it was a hard tax to avoid. Thanks to hearth money, the infrastructure was already in place to collect the tax. It also seemed a fair tax: the more windows somebody had, the wealthier they were likely to be and so the greater their ability to pay.

Like so much permanent government legislation, window tax was introduced on a temporary basis. The amounts payable were low at first, starting with a flat rate of two shillings per house with up to ten windows. But over the years, they crept up.

Soon, rather than pay, people began blocking up their windows. By 1718, it was already noted that the tax wasnt raising as much revenue as hoped. The reaction was not to lower the tax, but to increase it. The result was even more extreme avoidance tactics. Homes were built with fewer windows. Some were built with windows already bricked up, thus giving the owner the option to knock through and glaze at a later stage, if desired. In some cases, apartment buildings were constructed with entire floors of windowless bedrooms. At a time when electric, gas and oil lighting had not yet been invented and light came from the smoky flames of tallow candles or rush lights (reeds dipped in fat), blocking out sunlight and fresh air was no small sacrifice.

A further absurd impost on light,

The glass tax inhibited the growth of an entire industry. Between 1801 and 1851, the United Kingdom population grew from 11 million to 27 million.

Windows became a symbol of wealth, even in fiction. Elizabeth saw much to be pleased with, writes Jane Austen in Pride and Prejudice. Though she could not be in such raptures as Mr Collins expected the scene to inspire, and was but slightly affected by his enumeration of the windows in front of the house, and his relation of what the glazing altogether had originally cost.

Though the tax never made it to the USA, in 1798 fear of it sparked an entire rebellion the Fries rebellion. When assessors in Pennsylvania rode about surveying property for the Direct House Tax, German and Dutch settlers thought they were about to try and levy a window tax. They rose up in an armed revolt that spread across the state and took the federal troops of President John Adams the best part of two years to quash.

Nor did the window tax prove progressive. A house of 10 rent in the country, wrote Adam Smith, may have more windows than a house of 500 rent in London, Even so, the tax continued.

By the nineteenth century, opposition to it was everywhere. The adage free as air has become obsolete, fumed Charles Dickens. Neither air nor light have been free since the imposition of the window-tax. The motion, however, failed to pass. Only after another national campaign was the tax finally repealed in 1851. France would not repeal its version for another 75 years.

The window tax was just one tax and, in the context of history, not a particularly long-lived one, but it is a great example of how a tax comes into being and the consequences that follow. In its evolution we see the typical life cycle of a tax.

It is enacted at a time of need, usually to fund some kind of war. It is presented as temporary, but becomes permanent. The amount payable is low at first, but increases over time. It violates basic freedoms, in this case the right to light and fresh air. Many go to great lengths to avoid paying it, and it thus distorts how people behave and the decisions they make. There are all sorts of unintended consequences, which get worse as the tax matures. Much of the money raised is wasted or spent in a way with which the taxpayer does not agree. Finally people have had enough, and there is some kind of movement a campaign, a protest, even a revolution to get rid of it, which government is slow and reluctant to do.

It is too simplistic to say the window tax was good or bad. It worked well for a while, then it didnt. The money raised helped pay, among other things, for the essential defence of the nation. At its heart is the moral dilemma of so many taxes. On the one hand, it was an invasion of private property rights, with grave unintended consequences; on the other, it was the most practical solution at the time to pay for what some would deem to be the vital workings of government. We can see why Winston Churchill, among many others, described taxes as a necessary evil. The big question is: how much evil is necessary?

Next page