Foreword

If someone had asked me at the beginning of my career whether I could see myself writing a book like We Do Know How , I would have said no. For two reasons.

First, international development seized my attention in the 1960s, an era of government activism and distrust of business. Uncritically, I bought into that mindset. Like many of my peers, I looked to government to lead and saw business as almost a necessary evil. In writing We Do Know How , I have come practically full circle. Yes, government policy is a critical determinant of economic growth, job creation, and poverty reduction. The negative effects of poor government policies on economic performancethe sad state of failed states is the extreme case in pointare witness to that truism. But the mixed track record of governments in conceiving and implementing good policy also has to make one skeptical about government as the answer. Even when governments do get it right, where do economic transactions actually take place, where do jobs get created, and where do poor people earn the wherewithal to better their standard of living? In businesses! In the final analysis, the growth of businesses is not something just to tolerate; it is something to encourage, not only with government policywhose impact on businesses is often far from automaticbut, sometimes as or even more importantly, directly with businesses themselves.

Second, when I started in development, the halo effect of the Marshall Plan was still strong. As a young development economist, I was joining an optimistic profession. My job, as I conceived it then, was not to rock the boat but to take received wisdom, tweak it at the edges perhaps, and put it into practice. During the early years of my career, I was content to do just that. As time went by, though, I could not fail to notice that much of conventional development wisdom failed to deliver the results it promised. So my skepticism grew. Luckily, about 15 years ago in Peru I had the opportunity to shape an approach I thought had the potential to work. The approach did not work perfectlywhat ever does?but it did work demonstrably better than competing approaches. In recent years, I have been privileged to take lessons learned in Peru and, with appropriate adjustments, apply them in programs in more than a dozen other countries around the world. Again, the approach has not always worked perfectly, but it definitely has shown its adaptability to very different working environments. The result is what I now call the buyer-led approach to creating jobs for the poor, and that approach is the subject of this book.

What was the nature of the answers, the solutions, that Jonah caused us to develop? They all had one thing in common. They all made common sense, and at the same time, they flew directly in the face of everything Id ever learned.

Eliyahu M. Goldratt and Jeff Cox, The Goal , 3rd rev. ed. (Great Barrington, Massachusetts: North River Press, 2004), p. 267.

The buyer-led approach differs in a number of significant respects from much development practice. Among other things, the approach urges development practitioners to take market demand as their starting point, to set results targets and hold themselves accountable for them, to manage with discipline, to let clients binding problems dictate development solutions, to take numbers seriously. In practice, I have found that most development practitioners think the programs they manage already are demand-driven, results-oriented, accountable, and so on. I have also found that when you peel away the layers of the onion, that is very often far from the case. In writing We Do Know How , therefore, I have felt obliged not only to describe the buyer-led approach, but to draw contrasts with the flaws I see in other approaches. I have not done so willingly, but I see no other realistic alternative to convince readers that the buyer-led approach is not just old wine in a new bottle. In my experience, it is only when I draw out the differences explicitly that others can really appreciate just how differentsome of my colleagues would say revolutionarythe buyer-led approach really is, and just how much development practitioners need to shift gears from what they are currently doing to put the approach into practice effectively. In going through We Do Know How, therefore, please bear with the occasional negative commentary on other development practice. If the tone comes across as iconoclastic, it is not intentional. Iconoclast I may be, but a reluctant one.

In the end, We Do Know How appeals to development practitioners to step back from the day-to-day, keep an open mind, and let that mind learn from experience. Speaking of the 1960s, I quote from Lyndon Johnson in a broader context:

Most of all we need an education which will create the educated mind. This is a mindnot simply a repository of information and skills, but a source of creative skepticismcharacterized by a willingness to challenge old assumptions and to be challenged, a spaciousness of outlook, and convictions deeply held; but it is a mind which new facts can modify. For we are a society which has staked its survival on the rejection of dogma, on the refusal to bend experience to belief, and in the determination to shape actions to reality as reality reveals itself to us.

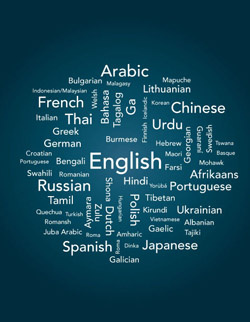

We Do Know How directs itself primarily to practitioners of development, broadly defined. Examples of development practitioners include employees of donor organizations (the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the development programs of other individual countries, the World Bank and other multilateral banks, the United Nations and affiliated agencies, etc.), developing country governments (Ministries of Economy, Agriculture, etc.), private voluntary organizations (CARE, Catholic Relief Services, Save the Children, World Vision, etc.), corporate social responsibility programs of large businesses, international development consulting companies, individual development practitioners, and university faculty and students. Since this audience is more heterogeneous than one would think at first blush, I have tried to write We Do Know How in plain, largely jargon-free English. The reader will judge whether I have succeeded.

If there is one group of readers to whom I direct this book preferentially, it is the young people crying for coherent development approaches that work. Almost every time I give a presentation to university students, they tell me how refreshing it is to hear from someone who has worked in the trenches. The students do not always agree with meno one doesbut they do jump at opportunities to hear from real, live practitioners. As much as they appreciate the importance of theory and policy, they are anxious to move from development writ large to how actually to conceive, design, and operate a micro development program. We Do Know How fills that niche and, ideally, can serve as a useful reference, even as a classroom text, for that purpose.

I am indebted to many parties for their assistance in transforming We Do Know How from the germ of an idea into a fully fledged product. Institutionally, I owe special thanks to two organizations. The first is USAID. I have had the enviable good fortune to work on USAID programs throughout the world, and that experience has shaped much of this book. The second organization is Chemonics International Inc., the international development consulting company where I have worked for most of the last two decades. Within Chemonics, my special thanks go to Ashraf Rizk, who urged me to write We Do Know How in the first place, to Richard Dreiman, Susanna Mudge, John Nittler, and James Butcher, who made it possible for me to break out substantial chunks of time to think and write, and to Douglas Tinsler for his unflagging enthusiasm from beginning to end. For assistance day to day, I am most indebted to Joseph Jordan, who served basically as my factotum through the writing process, helping me with equal adeptness both on content and on organization and presentation. Getting We Do Know How to this stage owes much to his support.