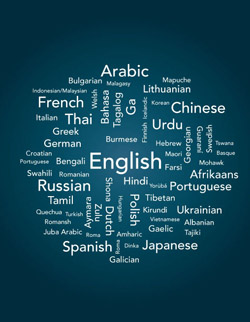

In almost every language there is a range of words related to jobs, each emphasizing a different angle. Some words hint at the nature of the activity being performed, evoking the skill or expertise that is required. Others refer to the volume of human inputs used in production, bringing images of effort and conveying a sense of physical exertion. There are also words associated with the sheer numbers of people engaged in economic activity, which are more easily associated with aggregate statistics. In other cases, what seems to be at stake is a contractual relationship, involving mutual obligations and a degree of stability. In some languages, there are even words to designate the place where the person works, or at least a slot in a production process. This multiplicity of words clearly shows that jobs are multi-dimensional and cannot be characterized by a single term or measured by a single indicator.

Words related to jobs do not always translate well from one language to another, as the range of options available in each case can be different. If languages shape thinking, there are times when the ways in which people refer to jobs seem to be at odds. Gaps probably arise from the different characteristics of jobs being emphasized in different societies. They also suggest that jobs agendas can differ across countries.

In many languages, words related to jobs serve not only as common nouns but also as proper nouns. Throughout history family names have been associated with specific skills or trades: Vankar in Hindi, Hattori in Japanese, Herrero in Spanish, or Mfundisi in Zulu, just to mention a few. The use of job-related words as household identifiers shows that people associated themselves with what they did. Nowadays, people aspire to choose their jobs based on what motivates them and on what could make their lives more meaningful. In almost every language there are also several words to express the lack of a job. Almost invariably these words have a negative connotation, close in spirit to deprivation; at times they even carry an element of stigma. In all these ways, language conveys the idea that jobs are more than what people earn, or what they do at work: they are also part of who they are.

Acknowledgments

This Report was prepared by a team led by Martn Rama, together with Kathleen Beegle and Jesko Hentschel. The other members of the core team were Gordon Betcherman, Samuel Freije-Rodriquez, Yue Li, Claudio E. Montenegro, Keijiro Otsuka, and Dena Ringold. Research analysts Thomas Bowen, Virgilio Galdo, Jimena Luna, Cathrine Machingauta, Daniel Palazov, Anca Bogdana Rusu, Junko Sekine, and Alexander Skinner completed the team. Additional research support was provided by Mehtabul Azam, Nadia Selim, and Faiyaz Talukdar. The team benefited from continuous engagement with Mary Hallward-Driemeier, Roland Michelitsch, and Patti Petesch.

The Report was cosponsored by the Development Economics Vice Presidency (DEC) and the Human Development Network (HDN). Overall guidance for the preparation of the Report was provided by Justin Lin, former Senior Vice President and Chief Economist, Development Economics; Martin Ravallion, acting Senior Vice President and Chief Economist, Development Economics; and Tamar Manuelyan-Atinc, Vice President and Head of the Human Development Network. Asli Demirg-Kunt, Director for Development Policy, oversaw the preparation process, together with Arup Banerji, Director for Social Protection and Labor.

Former World Bank President Robert B. Zoellick, President Jim Yong Kim, and Managing Directors Caroline Anstey and Mahmoud Mohieldin provided invaluable insights during the preparation process. Executive Directors and their offices also engaged constructively through various meetings and workshops.

An advisory panel, comprising George Akerlof, Ernest Aryeetey, Ragui Assaad, Ela Bhatt, Cai Fang, John Haltiwanger, Ravi Kanbur, Gordana Matkovi, and Ricardo Paes de Barros, contributed rich analytical inputs and feedback throughout the process.

Seven country case studies informed the preparation of the Report. The case study for Bangladesh was led by Binayak Sen and Mahabub Hossain, with Yasuyuki Sawada. Nelly Aguilera, Angel Caldern Madrid, Mercedes Gonzlez de la Rocha, Gabriel Martnez, Eduardo Rodriguez-Oreggia, and Hctor Villarreal participated in Mexicos case study. The study for Mozambique was led by Finn Tarp, with Channing Arndt, Antonio Cruz, Sam Jones, and Fausto Mafambisse. For Papua New Guinea, Colin Filer and Marjorie Andrew coordinated the research. The South Sudan study was led by Lual Deng, together with Nada Eissa. AbdelRahmen El Lahga coordinated the Tunisian work, with the participation of Ines Bouassida, Mohamed Ali Marouani, Ben Ayed Mouelhi Rim, Abdelwahab Ben Hafaiedh, and Fathi Elachhab. Finally, Olga Kupets, Svitlana Babenko, and Volodymyr Vakhitov conducted the study for Ukraine.

The team would like to acknowledge the generous support for the preparation of the Report by the Government of Norway through its Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the multidonor Knowledge for Change Program (KCP II), the Nordic Trust Fund, the Government of Denmark through its Royal Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the Government of Sweden through its Ministry for Foreign Affairs, and the Government of Japan through its Policy and Human Resource Development program. The German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development Cooperation (BMZ) through the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) organized a development forum that brought together leading researchers from around the world in Berlin.

Generous support was also received for the country case studies by the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), Canadas International Development Research Centre (IDRC), the Government of Denmark through its Royal Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) through the JICA Institute, and the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). The United Kingdoms Overseas Development Institute (ODI) assisted the team through the organization of seminars and workshops.

A special recognition goes to the International Labour Organization (ILO) for its continued engagement with the team. Jos Manuel Salazar-Xiriachs and Duncan Campbell coordinated this process, with the participation of numerous colleagues from the ILO. Interagency consultations were held with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). The team also benefited from an ongoing dialogue with the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

Country consultations were conducted in Bangladesh, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, India, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Mexico, Mozambique, Norway, Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom. All consultations involved senior government officials. Most included academics, business representatives, trade union leaders, and members of civil society. In addition, bilateral meetings were held with senior government officials from Australia, the Netherlands, South Africa, and Spain.

Consultations with researchers and academics were arranged with the help of the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) in Kenya, the Economic Research Forum (ERF) in the Arab Republic of Egypt, and the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association (LACEA) in Chile. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) organized special workshops with its research network in Germany and Turkey, coordinated by Klaus Zimmerman. Forskningsstiftelsen Fafo in Norway undertook a household survey in four countries, which this Report draws on.