Contents

Figures

First published in the UK in 2020 by Intellect, The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds, Bristol, BS16 3JG, UK

First published in the USA in 2020 by Intellect, The University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Copyright 2020 Intellect Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copy editor: MPS Technologies

Cover designer: Aleksandra Szumlas

Production manager: Emma Berrill

Typesetting: Contentra Technologies

Print ISBN 978-1-78938-192-4

ePDF ISBN 978-1-78938-193-1

ePUB ISBN 978-1-78938-194-8

Printed and bound by TJ International, UK.

To find out about all our publications, please visit www.intellectbooks.com.

There, you can subscribe to our e-newsletter, browse or download our current catalogue, and buy any titles that are in print.

This is a peer-reviewed publication.

There are too many people to adequately thank for their support and insights in the writing of this book. Both Stuart Marshall and Marc Karlin died in the 1990s, so my research into their work has relied on their films, videos, writings and a series of informal interviews that I have conducted with their friends and colleagues. Interviewees or rather, those who I have had rambling and productive conversations with include: Holly Aylett, the co-ordinator of the Marc Karlin archive; Neil Bartlett, who knew Marshall and appeared in his video Pedagogue (1988); Simon Blanchard, who oversaw the activities of the Independent Filmmakers Association (IFA) in the 1980s; Jonathan Bloom (previously Collinson), the cinematographer who filmed a number of Marc Karlins projects; Anne Cottringer, the cinematographer who filmed Bright Eyes, among other independent films; the video artist Dave Critchley who knew Marshall as a colleague and friend; independent film-maker Jill Daniels; Barbara Evans, a film-maker involved in the London Womens Film Group; Rebecca Dobbs, a founder member of Maya Vision, the company which produced a number of Marshalls television works; Paul Marris, who was a significant presence in independent film groups such as the IFA, the Other Cinema, Faction Films and Trade Films; Laura Mulvey, the film-maker and theorist who was involved in the IFA from its early meetings in the mid-1970s; Sheila Rowbotham, the socialist-feminist historian who was at the forefront of the Womens Liberation Movement in the 1970s, and who was a close friend of Karlin; Jeffrey Weeks, the historian, activist and theorist of sexuality; Cate Elwes who knew Marshall as a student and friend; David Curtis, Steven Ball and Duncan White at the British Artists Film and Video Collection; and Steve Presence from the Radical Film Network. For feedback on drafts, and fruitful discussions at screenings and conferences, I would also like to thank James Swinson, Lucy Reynolds, Sylvia Harvey, Pratap Rughani, Claire Holdsworth, Alison Green, Erika Balsom, Nick Helm-Grovas, Sue Clayton, Laura Mulvey, Cate Elwes, Janet McCabe, Pooja Rangan, Benjamin Cook, Conal McStravick and Dan Kidner. Thanks also to all of my wonderful undergraduate and postgraduate students at Central Saint Martins, University of Westminster and Arts University Bournemouth.

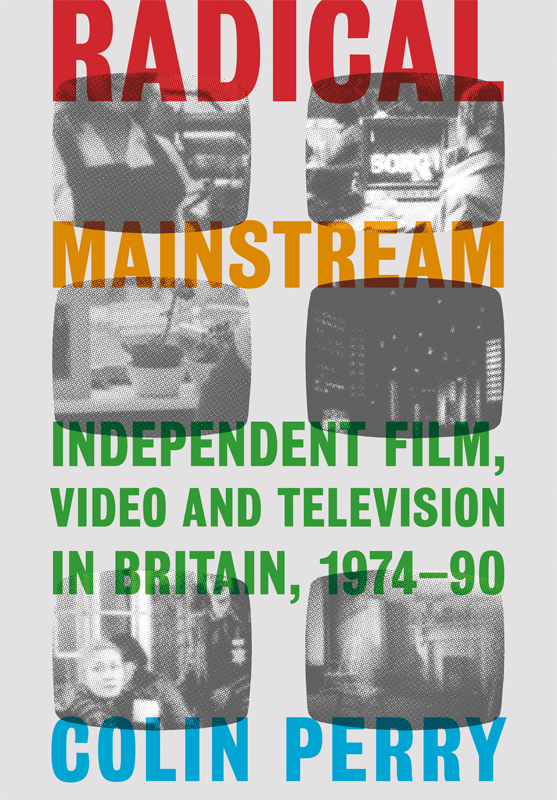

What happens when radical cultures gain access to the mass media? This book addresses this question through an analysis of the relations between radical independent film and video practices in Britain and public service television from the mid-1970s to the late-1980s. This enquiry is urgent today because of the ongoing need for engagement, resistance and organization against the consolidation forces of the Right. If there is a nostalgic glow still emanating from this earlier era of widespread socialist activity, we should not be deluded that the past is a sealed box. Instead, by looking back at the past we can release its energies, rediscover its organizational logic and reignite its persuasive powers for our own urgent present moment. During the 1970s and 1980s, film-makers, video activists, artists and theorists from the fragmented Left fought for access to British television, which was partly achieved with the launch of Channel 4 in 1982. While this arena had been largely closed to the voices of dissent that emerged over the post-war period and the 1960s, by the early 1970s, television had become a site of struggle around social and political movements rooted in Marxism, the Womens Liberation Movement, anti-racism, Gay Liberation and others. In fighting to gain access to the airwaves, film-makers of the fractured Left joined together to change governmental attitudes, legislation and institutional practices.

By the 1990s, television was certainly more open and diverse, more receptive to socialist, women, queer and black voices. But the period covered in this study also ends in a sense of gloom, with the apparent exhaustion of radical Left energies, where every oppositional impulse seemed to be absorbed or pre-absorbed by capitalism. It is a crisis that still haunts us, notably with the corporate medias hold over the networked society (Castells 2010) of social and online media. But the hegemonic form of neoliberalism has also recently and spectacularly collapsed giving birth to terrible monsters from Trump to Brexit, as well as the thrilling possibilities of a new populist socialist politics (Fraser 2019; Mouffe 2018). Our present era has returned to a maelstrom of energies not felt for several decades. It is my contention that the vitality of both these periods is contained within the rich eddies and flows of discourse, organization and activism, as well as the intersections between experimental aesthetics and political content. Such eras open up a flush of hope, where despite serious disagreements between Left factions, moments of cooperation can produce real effects. I argue in this book that independent film and video can be considered a signal form of such organization: a set of counterpublics: not a single movement, but a set of ad hoc alliances that come together to reshape social and political ideals more widely.

In examining the area in terms of diverse publics, I also wish to overcome two of the main problems with many existing accounts of independent film and video in Britain during this period. First, films and videos from this period are often analysed as separate to the sociopolitical movements that they emerged from or jostled with. Partly, this lacuna is an effect of the dominant film theories of the 1970s, which understood films as texts that have causal effects on viewers. That is to say, the power of film or cinema was understood to emanate from the film text and the cinematic encounter itself, not from the wider network of debates these were part of (see Chapter 1). Subsequent theories of affect in film studies since the 1990s have proved rich analysis of specific films; but they have not generally engaged with their social force, or how and where films or videos were originally received by audiences. Films and videos that were originally funded or commissioned for television broadcast, such as