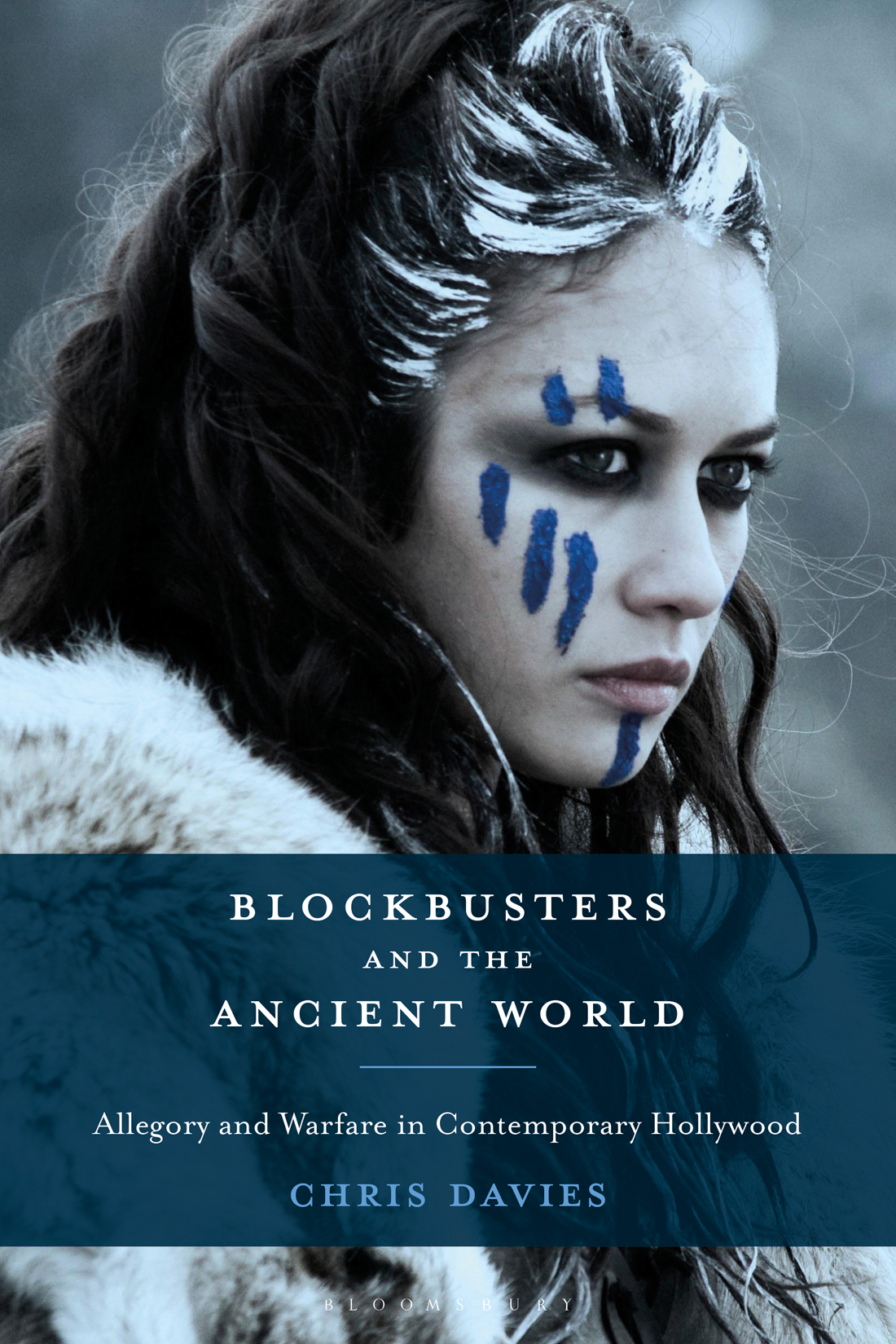

BLOCKBUSTERS AND THE ANCIENT WORLD

BLOCKBUSTERS AND THE ANCIENT WORLD

Allegory and Warfare in Contemporary Hollywood

Chris Davies

Contents

Achilles (Brad Pitt) drags Hectors (Eric Bana) corpse behind his chariot in Troy. |

The citizens of Troy flee from fires, in Troy . |

Achilles (Brad Pitt) looks over the Greek beach landing in Troy. |

Philip (Val Kilmer) shows a young Alexander (Connor Paolo) a painting of an eagle pecking Prometheus liver in Alexander. |

The eagle flies over the opposing armies at Gaugamela in Alexander. |

Alexander (Colin Farrell) leads his army through the jungles of India in Alexander. |

Ptolemy (Anthony Hopkins) dictates his biography of Alexanders life to his scribe, Cadmus (David Bedella), in Alexander. |

Gorgo (Lena Headey) addresses the Spartan Council in |

Leonidas (Gerard Butler) in |

Ephialtes (Andrew Tiernan) in his Persian uniform in |

A Persian Immortal is unmasked in |

Dilios (David Wenham) addresses the Spartans around the camp fire in . |

Bors (Ray Winstone) mocks Horton (Pat Kinevane) in King Arthur . |

Guinevere (Keira Knightley) is held prisoner in a dungeon in King Arthur |

Fireballs roll towards the Ninth Legion in Centurion |

Etain (Olga Kurylenko) and Gorlacon (Ulrich Thomsen) watch the Ninth Legions eagle standard burn in Centurion . |

Marcus (Channing Tatum) and Esca (Jamie Bell) meet the Seal People in The Eagle . |

The knights return to Hadrians Wall in King Arthur . |

Marcus (Channing Tatum) and Esca (Jamie Bell) approach Hadrians Wall in The Eagle . |

The Roman wagon train is ambushed by Woads in King Arthur |

Hadrians Wall under construction in Centurion |

Marcus (Channing Tatum) and Esca (Jamie Bell) exit the Roman hall in The Eagle . |

Cyril (Sami Samir) in Agora . |

The camera rises up to give an overview of the religious riots in the streets of Alexandria in Agora . |

Roman guards prepare to beat Jesus in The Passion of the Christ . |

Satan (Rosalinda Celentano) and his baby (Davide Marotta) in The Passion of the Christ . |

Rhesus (Tobias Santelmann) is chained up and mocked, in Hercules |

Hercules (Dwayne Johnson) leads the army of Lord Cotys (John Hurt) into battle, with Iolaus (Reece Ritchie) to his left, in Hercules |

Malek (Isaac Andrews) in Exodus: Gods and Kings . |

Ben-Hur (Jack Huston) and Messala (Toby Kebbell) are reunited with their loved ones and each other, in Ben-Hur. |

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the copyright material in this book. The third-party copyrighted material displayed in the pages of this book are done so on the basis of fair dealing for the purposes of criticism and review or fair use for the purposes of teaching, criticism, scholarship or research only in accordance with international copyright laws, and is not intended to infringe upon the ownership rights of the original owners.

This book is the product of many years of hard work, but could not have been completed without the input and encouragement of a number of people. Id like to thank James Lyons, Helen Hanson, Phil Wickham, Joe Kember, Andrew McRae, Danielle Hipkins and all those at the University of Exeter who taught and guided me, and helped make this possible. Thanks also to Andrew Pepper and Gideon Nisbet for their input and support, and to all those at IB Tauris/Bloomsbury for turning my ambition into a reality.

Special thanks go to Edward Lamberti for his friendship, humour and valued advice throughout the process of finishing my thesis and writing this book: one can never have enough study-breaks to discuss James Bond films! Huge thanks also to Graham Hill, Karen Myers, Jacob Smith and everyone at the BBFC for their kindness and assistance.

My love and thanks go out to all my friends and family, especially my parents, who have encouraged, tolerated and stuck with me throughout the process of writing this book. You mean the world to me.

Finally, thanks to Ridley Scott, Peter Jackson, Steven Spielberg, Oliver Stone and all the filmmakers whose work has inspired me, both in life and in the creation of this book. What you do in life echoes in eternity.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions in the above list and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

These antiquarian extravaganzas are ultimately not about Abraham or Ben Hur, Spartacus or Maximus, or about anonymous Christian martyrs and converted centurions, but about ourselves, or, more precisely, about our ideals, conveniently presented in the flattering but distancing guise of armour and toga and confirmed by the authority of the past.

Amelia Arenas vignette, quoted above, is emblematic of a commonly held view within scholarly criticism of ancient world epics in cinema. The presumption that films in this genre are as much, if not more, about the period and culture in which they are produced than about that which they depict has been repeated to the point that it could be mistaken for a truism. Jeffrey Richards, for instance, opens his monograph on the subject by stating, Historical films are always about the time in which they are made and never about the time in which they are set. In practice, however, the study of meaning in ancient world epics is rarely this straightforward. How one interprets a filmic text is influenced by the personnel involved in its production, its marketing, reception, contemporary zeitgeist, the motives of the author, the source material, and the viewers personal response. Adopting a multivalent perspective, this book assesses the extent to which recent ancient world epics engage with their present or else embody recurrent themes in history and the genre itself. In so doing, it explores how the films released after Gladiator (2000) have evolved, with particular emphasis on their relationship to the mid-twentieth-century epic cycle and the role of warfare in facilitating change.

Ancient world epics possess a liminality whereby they exist as works of filmic art, products of the entertainment industry and, theoretically, as pieces of historical analysis. Their status as multivalent texts encompassing a cornucopia of topics has intrigued scholars from various disciplines. The research for this book, for instance, traversed aspects of ancient, modern and cinematic history, mythology, religion, politics, genre and auteur theory, reception studies and masculinity and the male body. To date, the majority of scholarship on the ancient world in cinema has been devoted to what is arguably the genres most iconic and popular period dating roughly from the release of Samson and Delilah in 1949 to The Bible: In The Beginning in 1966. As sources differ on the exact dates of this period I refer to it simply as the 1950s60s cycle, which includes such films as Ben-Hur (1959), The Robe (1953), Spartacus (1960) and Cleopatra (1963). The ancient world epics popularity dissipated during the 1960s due to a confluence The market had also been saturated with cheaply produced Italian muscleman epics that contributed to the ancient world epic becoming kitsch and the subject of parody, most famously in Monty Pythons Life of Brian (1979). The ancient world still found form across the 1970s and 1980s, in such productions as the television miniseries Masada (1981) and Martin Scorseses adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis novel The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Other genres likewise alluded to the ancient world epic, such as the sci-fi adventure Star Wars (1977) and its subsequent sequels and prequels. The films of the 1950s60s cycle were also kept in the public consciousness through home media releases and repeated screenings on television; even today, Easter or Christmas in the United Kingdom is not complete without a screening of 1959s Ben-Hur .