This study seeks to examine both the attitudes of the Jewish community (the Yishuv) in Palestine (Eretz Yisrael) and of the Zionist leadership toward the massacres committed by the Turks against the Armenians at the turn of the twentieth century. These atrocities began in the last decade of the nineteenth century and reached their peak in the massive destruction of Armenians during the First World War. This book seeks also to make the reader aware of the genocide of the Armenian People.

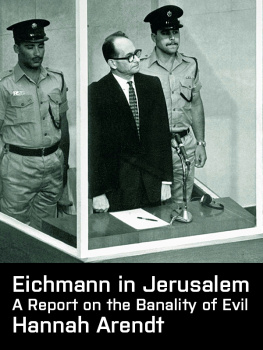

At the same time, the book raises theoretical and philosophical questions, particularly in the introduction and final two chapters, which relate directly and indirectly to the specific subject of our research: the debate over the concept of genocide, and the uniqueness of the Holocaust in comparison to other instances of genocide, including the Armenian genocide.

The opening chapter presents a short historical survey of the history of the Armenians and a description of the events connected to their destruction. Part of the body of research discusses the events in Palestine during the First World War which, directly and indirectly, subjectively and objectively, were related to the destruction of the Armenians. The purpose of the discussion is to expose an aspect of the history of the Yishuv during the War from a perspective previously neglected by the historiography.

The central part of the book comprises chapters that discuss The Reactors (to the destruction of the Armenians) and The Indifferent (to it). The quantitative division between The Reactors (the larger part) and The Indifferent (the smaller part) should not mislead us. In reality, the vast majority of the Yishuv was indifferent and only a small minority reacted.

This research is the result of an ongoing effort to examine a subject that has been repressed and ignored in the Israeli historical and collective memory, as well as in the collective memory of the world, and thus has disappeared from our historical consciousness. I became involved in the subject in the framework of my activity as a researcher of contemporary Jewish studies and as an educator. I was troubled by a sense of oppressive discomfort and criticism of the evasive behavior, verging on denial, of the various governments of Israel regarding the memory of the Armenian genocide and I wanted to examine both the overt factors and the deeper and more complex factors leading to such behavior which to me seems morally unacceptable, particularly since we Jews were victims of the Holocaust.

After I began to explore the motives for the present behavior regarding the Armenian genocide, I realized that the issues must be examined from the beginning, i.e., from the period in which they occurred. For more than ten years, I have been involved in the subject and my research has carried me to unanticipated places and events. It has revealed to me, I must confess, a reality that I did not expect. I had hoped to fmd a greater degree of identification with the suffering of the Armenians, more empathy, and more attempts to help, within the scope of our very limited possibilities. Instead I found much indifference and an attitude that stressed the particular rather than the universal.

I have chosen as the motto of the present book a passage from our Jewish sources: Thus was created a single man, to teach us that every person who loses a single soul, it shall be written about him as if he has lost the entire world, and every person who sustains a single soul it shall be written about him as if he has sustained the entire world. (Mishna, Sanhedrin, IV, 5).

This passage was revised in later versions and the phrase from the People of Israel was added so that the line no longer reads every person who sustains or loses a single soul, but rather every person who sustains or loses a single soul from the People of Israel. In editions of the Mishna generally available today we usually find the later amended version.

In this context, it is worth quoting one sentence from In Praise of Forgetting, a controversial article by Yehuda Elkana that appeared in the Hebrew daily newspaper, Haaretz, on March 2, 1988. Elkana wrote, From Auschwitz came, in symbolic terms, two peoples: a minority which claims it will never happen again, and a frightened and anxious majority which claims it will never happen to us again.

Between those two versions, in the tension between particularism and universalise!, fluctuates Israeli society and the public debate within it. The crime of genocide is an extreme and total case of harm, inflicted by human beings on other, innocent human beings. One of the indirect aims of this book is to increase our sensitivity to this aspect of human lifebeyond what has happened to us; to raise awareness to the occurrence of genocide or genocidal acts in the past and the present, before our very eyes, and to the danger of its occurrence in the future. In the course of recent years such atrocities took place on a broad scale in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda. It is important, I believe, to encourage the individual to think about this phenomenon, to examine his stand, his personal responsibility, and his possibilities to react. Genocide is an evil against which we must straggle in order to minimize its appearance as far as possible.