All rights information:

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

First printing 2021

2021 Michael Ratner

Published by OR Books, New York and London

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Typeset by Lapiz Digital. Printed by Bookmobile, USA, and CPI, UK.

paperback ISBN 978-1-68219-309-9 ebook ISBN 978-1-68219-250-4

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

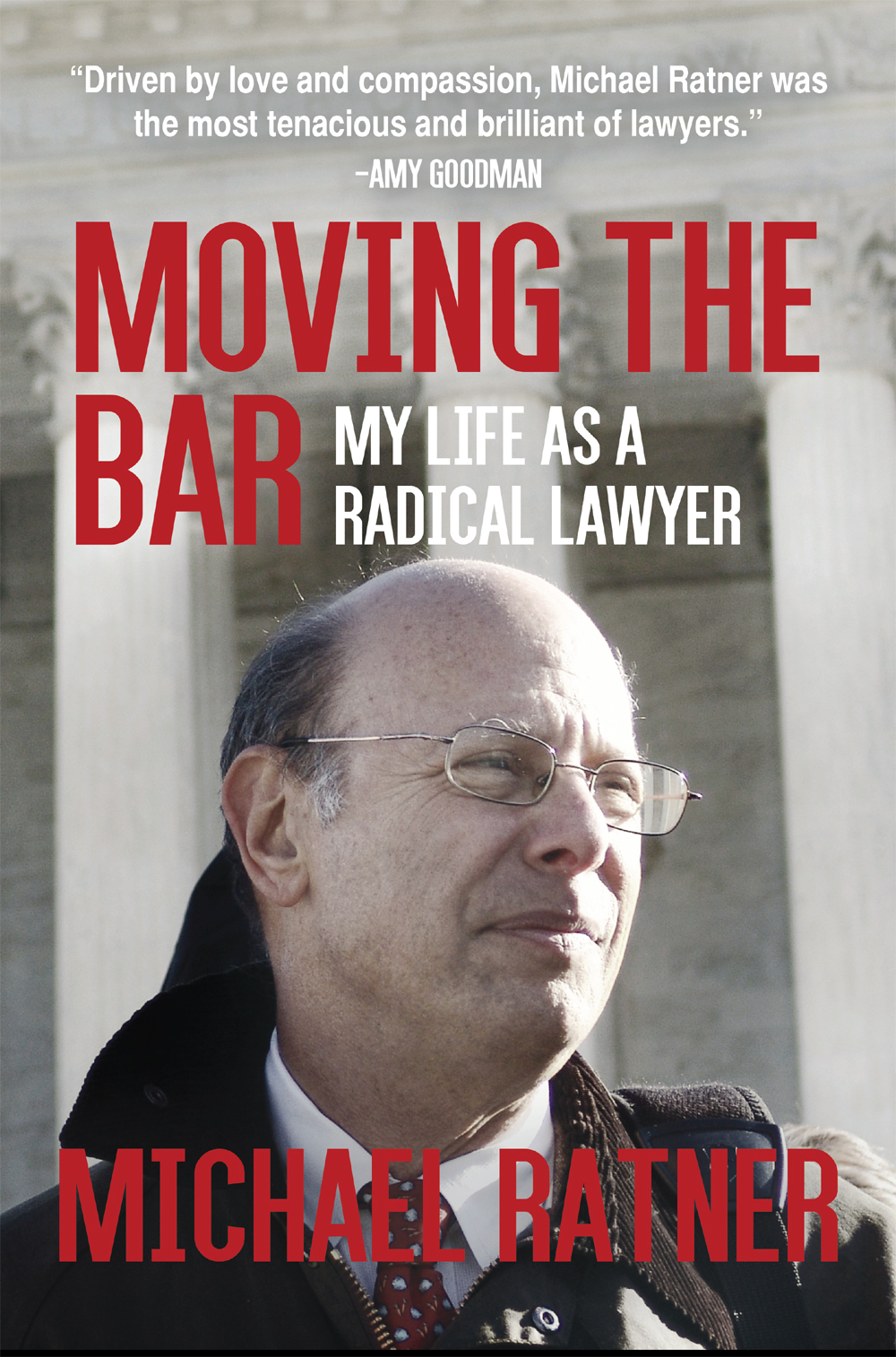

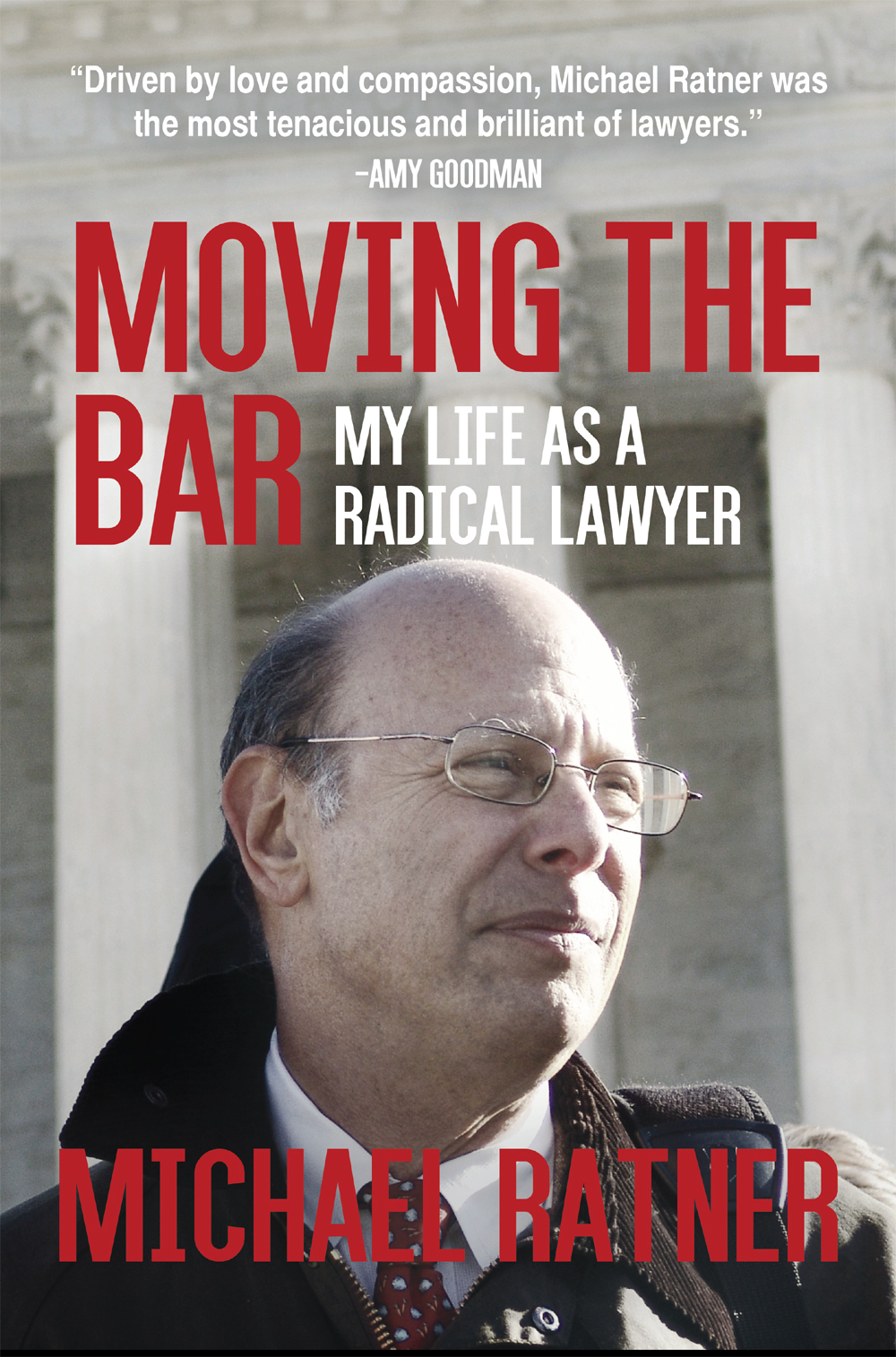

This is the story of a first-generation Jewish kid from a huge Polish immigrant family in Cleveland who was radicalized in the sixties, settled in New York, and became one of the great civil and human rights attorneys of his generation: truly a widely beloved lawyer for the left.

After law school Michael was expected to go back to Cleveland to join the family building supply business. His uncle advised against becoming a lawyer, warning that a lawyer always works for someone else. With great pain, Michael ignored his uncles advice. He began working for someone else. That someone else was the left.

Michael worked for some 40 years at the Center for Constitutional Rights, first as a staff attorney, then litigation director and finally its president. He liked to refer to the Center, in Alexander Cockburns words, as a small band of tigerish people. He put the CCR on firm financial footing, enabling it to continue its work for human rights and social justice as a robust supporter of grassroots organizations. Michael went on to help his friend and colleague, the Berlin attorney Wolfgang Kaleck, establish the European Center for Human and Constitutional Rights as a kind of sister organization of the CCR. Back home he helped establish Palestine Legal to defend supporters of the Palestinian people against what Michael called the Palestine exception to the first amendment.

I first met Michael Ratner 35 years ago when we lived around the corner from each other in Greenwich Village. He had just been elected president of the National Lawyers Guild and came over to ask me to be on the editorial board of the organizations magazine Guild Notes. We became dear friends and worked together over many years.

Michael admired people who acted on their convictions, people who lived their lives, he told me, without any contradictions. John Brown, who attempted to support a slave uprising, was such a person. Vladimir Ilych Lenin was another (an oil portrait of Lenin hung in Michaels living room). And especially Che Guevara.

Together we wrote two books on Che and traveled to Havana twice to research and promote them. On the second trip when working on our book Who Killed Che?: How the CIA Got Away with Murder we met with General Harry Pombo Villegras. Pombo started fighting alongside Che as a shoeless peasant boy during the Cuban revolution (1956-59) and fought with him in Bolivia 10 years later. He was one of the three who escaped capture and execution by managing to walk over the Andes mountains into Chile. For our interview, Pombo wore a T-shirt and a baseball cap. When it ended, we offered him a car ride home but he declined, telling us he would walk back. Michael admired Pombos modesty, as well as his courage.

Michael himself was a modest person. In all the years I knew him he never told me that he had finished first in his class at Columbia Law School. Michael was also unfailingly generous. When I asked him once whom he helped out, he replied, Anyone who asks me. Michael was playful and funny and fun to be around. We used to tease him saying that there was no joke too silly, too puerile, for him not to relate. He loved his children and being with his family. Indeed, he loved all children, whom he called darlings.

In 2004 we started the radio show Law and Disorder on WBAI in New York City with Heidi Boghosian and Dalia Hashad. It is now broadcast nationally on 120 stations. Doing the show with Michael was really a pleasure. And easy. He was so smart we could ad lib. When Heidi and I do the show now, we prepare a written introduction and a list of questions for our guests.

Five years ago, Michael wrote a chapter for Imagine: Living in a Socialist USA, a book I co-edited with Frances Goldin and Debby Smith. Michaels chapter was called What I Would Do As Attorney General. His opening sentence was It will be a cold day in hell when a person with my politics is appointed to be attorney general of the United States. He wrote that If I did get to take office, I would begin by not enforcing certain laws, which I have a right to do. Then I would investigate and prosecute the real bad guys.

Michael taught human rights law to students at Columbia Law School with his friend Reed Brody. Then he began commuting from New York to New Haven where he taught at an international human rights clinic. It was there that he and his class won an historic victory protecting Haitians infected with HIV virus who were initially confined by the U.S. at its military base in Guantnamo, Cuba.

Perhaps Michaels greatest victory came in his initiating and organizing some 600 lawyers in firms large and small across the country to come to the defense of Muslim prisoners accused of terrorism and held at Guantnamo after 9/11. The government invented an indefinite detention scheme claiming the captives had no right to be brought before a judge, charged, and brought to trial, that neither international nor American law applied to them, that they had no right to habeas corpus. The team Michael assembled took the case all the way up to the United States Supreme Court, where they won. Nevertheless, the offshore prison camp of Guantnamo remains open to this day.

Justice is a constant struggle. This is the motto of the National Lawyers Guild. Michaels friend and colleague Bill Kunstler used to say that there are no green pastures, that every generation has its own battles to wage. That is why Michael wrote this book. He meant it to be both instructive and inspirational, especially for law students and young lawyers. When he died of cancer three years ago in May of 2016, Michael hadnt been able to finish the book. As sick as he was, he had gotten up to the year 2000. Karen Ranucci, Michaels wife and comrade, asked their friend, the writer Zachary Sklar, to finish the project, bringing it up to 2016. Zach was able to do this using Michaels notes and articles, previous interviews with Michael, and the recollections of his family members and legal colleagues.

As a lawyer and as an activist, Michael participated in the essential struggles of his times. He came to be, in the words of Lenin, as radical as reality itself. He could sense the future in the instant, as Shakespeare wrote. He understood that those who are above the struggles are also beside the point.

Michael was a Jew, but came to reject the idea that it was racial ties or bonds of blood that made up the Jewish community. He rejected Jewish nationalism in favor of an unconditional solidarity with the persecuted and exterminated. Michael had no funeral. He wasnt religious. Religion to him was superstition. The Jewish heretic who transcends Jewry belongs to a Jewish tradition the non-Jewish Jew, in the words of historian Isaac Deutscher. Michael was in line with the great revolutionaries of modern thought who went beyond the boundaries of Judaism: Spinoza, Heine, Marx, Luxembourg, Freud, and Einstein.

Next page