Contents

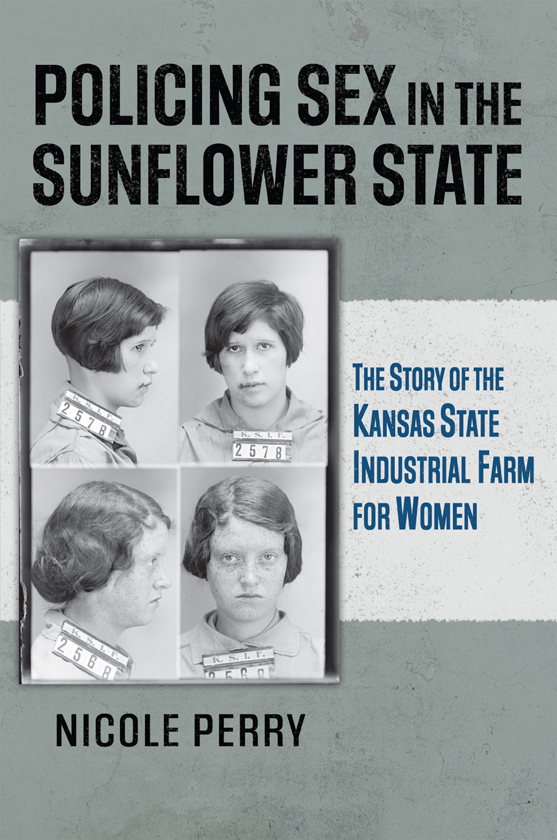

Policing Sex in

the Sunflower

State

Policing Sex in the Sunflower State

The Story of the Kansas State Industrial Farm for Women

nicole perry

university press of kansas

2021 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Perry, Nicole, author.

Title: Policing sex in the Sunflower State : the story of the Kansas State Industrial Farm for Women / Nicole Perry.

Description: Lawrence : University Press of Kansas, 2021 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020040364

ISBN 9780700631872 (cloth)

ISBN 9780700631889 (paperback)

ISBN 9780700631896 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Kansas State Industrial Farm for Women. | Reformatories for womenKansasHistory20th century. | Women prisonersKansasHistory20th century. | Sexually transmitted diseasesGovernment policyKansasHistory20th century. | WomenSexual behaviorKansasHistory20th century. | Sex discrimination against womenKansasHistory20th century. | SexKansasHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HV9306.L362 K3674 2021 | DDC 365/.978138dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020040364.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in the print publication is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992.

This book is dedicated to the women imprisoned

under Chapter 205 in Kansas.

May we hear your stories now, and do better.

contents

preface

As I work on the final edits of this book in the spring of 2020, the world has been gripped by the COVID-19 pandemic. The death toll ticks higher as government leaders struggle to stem the spread of this highly contagious virus. Countries across the world are in lockdown, millions are unable to work, and entire industries face economic collapse.

Perennial questions in public health about the balance between the public good and individual freedoms have been put to the test on an unprecedented scale as states across the country have closed schools and businesses and issued stay-at-home orders. While the majority of Americans support these measures, these restrictions have also met with resistance. Protestors are lobbying state governments to open back up, while public health experts warn of potential resurgences of the virus without adequate testing and a targeted approach to reopening.

Resistance to public health measures aimed at reducing the spread of disease are not new. During the 1918 flu epidemic, which some have argued should have been called the Kansas Flu due to its possible origin in the state, some people were impatient to emerge from isolation orders and resistant to wearing masks in public. Eager to celebrate the end of World War I, Americans ignored mass-gathering restrictions. Resurgences of the flu took off across the country, leading to a death toll of some 675,000 Americans by the end of the pandemic. Public health measures to prevent the spread of disease need the voluntary compliance of a critical mass of the population, requiring public health officials to understand not just the science behind diseases spread but also the whims of human behavior.

The COVID-19 pandemic is amplifying and exacerbating stereotypes, inequalities, and social divisions in the United States. The blame for disease outbreaks has a long history of coming down on stigmatized groups, including associations between African Americans and cholera, the gay community and HIV/AIDS, and immigrants and the poor in the case of syphilis and gonorrhea in the 1910s and 1920s. Asian Americans are reporting increased incidents of racial harassment as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, which originated in China. As people search for a scapegoat, deep-seated stereotypes rear their ugly heads. The virus is also exposing gaps in health-care infrastructure, the social safety net, and existing health disparities, leaving behind higher mortality rates for racial minority groups. Kansas, the place central to this book, has one of the highest rates of racial disparities in infection and death rates from COVID-19, with Black Kansans amounting to nearly a third of the states deaths from the virus, yet accounting for only 5.6 percent of the states population. Prisons, which were used in the time of this book as a place to contain the spread of syphilis and gonorrhea, are emerging as epicenters of coronavirus outbreaks. This pandemic, like many throughout history, has exposed and amplified the fault lines in society for all to see.

Kansas has not been immune from the effects of COVID-19. While confirmed infections are currently lower here than they are in many other parts of the country, the death toll, social consequences, and economic impact have been devastating, especially for those who are most vulnerable. The idea of quarantine, something that has seemed like an abstract idea to me as I have worked on this research over the past several years, is now a part of the daily reality for many Kansans, as it is for people across the globe. In Kansas the set of laws that provide the legal basis for public health restrictions have their roots in the events detailed in this book. A little-known statute called Chapter 205, first passed in 1917 and used to detain women who had syphilis and gonorrhea in the interwar period, is still on the books today in amended form, giving state authorities broad powers to address the coronavirus outbreak. The Kansas legislature passed further guidelines for quarantine and county-level health officers in 2005, adding more clarity to the procedures to be followed and providing recourse for individuals to challenge quarantine orders in court. Legal challenges to forced quarantine orders are few and far between, given how rarely states have ordered them on a wide scale. However, among those legal precedents that support the states power to quarantine its citizens in Kansas are cases dating back to the 1920s and 1930s, when men and women filed suit to challenge their confinement under Chapter 205 for venereal diseases.

The impact and historical legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic remain to be written. As you read this book to hear the story of another time, another cast of characters, another public health crisis, and, unfortunately, a very similar set of social inequities, my hope is that we can use the lessons learned from Chapter 205 to navigate and move forward from our current situation. The social systems in which the story of Chapter 205 played outthe prison system and the health-care systemare structuring the evolution of the COVID-19 outbreak as I write, and they will be at a crossroads as we look to define what postpandemic life looks like in the United States. While pandemics expose our social fractures, they also provide an opening to confront them and reenvision how our society is structured and whom it serves.

acknowledgments

I would like to thank the many people who helped shape this book and supported me personally while I worked on it. First, this project would not have been possible without the continued guidance and support from Brian Donovan, who saw some glimmer of hope in those first awful papers I turned in during graduate school and has read countless iterations of the chapters contained in this book. Everyone should be so lucky to have such an outstanding mentor and friend. I would also like to thank Bill Staples and Katie Batza, whose feedback and advice through the initial stages of this research and the publishing process have been critical to keeping the project on track. The outstanding staff and editors with the University Press of Kansas, including Kim Hogeland and David Congdon, as well as the reviewers for this manuscript, provided excellent feedback that improved this book tremendously. Early versions of this research also benefited from the insights of Aislinn Addington, Christy Craig, Jane Webb, and Gabriella Smith. I would like to thank the many archivists and librarians who assisted with this project, including the staff at the Kansas State Historical Society and the Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas. The Midwest Sociological Society and several offices at the University of Kansas, including the Department of Sociology, the Hall Center for the Humanities, and the Office of Graduate Studies, provided critical financial support to early stages of this research. I am grateful for the opportunity that these grants afforded me to move forward with this research.